Utilising RFID in Retailing: Insights on Innovation

Table of Contents:

- Abstract

- Executive Summary

- Foreword

- Background and Context

- Findings

- - Intrinsic Value of the Plateau of Productivity

- - The Omni Channel Imperative

- - RFID and Self-checkout

- - Facilitating Retail Loss Prevention

- Plans for Innovation in the Use of RFID

- Conclusions

- - The Value of Unique Product Identification (UPI)

- - Enterprise-wide Inventory Visibility – BAU and the Omni Channel Imperative

- - Informing the Management of Loss Prevention

- - Delivering an Enhanced Consumer Experience

- Stages of RFID Maturity

- The Future of RFID in Retailing

Languages :

This report presents results from a study focussed upon developing insights on how retail users of RFID have innovated in their use of the technology. It builds upon the findings presented in the joint ECR Retail Loss Group/GS1 UK Study published in 2018: Measuring the Impact of RFID in Retailing: Key Lessons from 10 Case-study Companies.

It is based upon an online survey of retailers and interviews with representatives from companies taking part in the original study and other retailers that are also using RFID. In total 25 companies responded to the online survey and 13 in-depth interviews were carried out.

The study found that the core business case identified in the 2018 study remained a consistent strategy adopted by most of the retailers taking part in this study – counting stock in physical retail stores with a handheld reader to achieve improved inventory accuracy. The primary justification remained the value this brought in terms of increased sales, reducing staff costs and stock holding, and in some cases, bringing down the value of retail losses. Beyond this, innovation was largely found to be incremental in nature and tightly bound by the need for a robust business case to be clearly present.

Abstract

This report presents results from a study focussed upon developing insights on how retail users of RFID have innovated in their use of the technology. It builds upon the findings presented in the joint ECR Retail Loss Group/GS1 UK Study published in 2018: Measuring the Impact of RFID in Retailing: Key Lessons from 10 Case-study Companies.

It is based upon an online survey of retailers and interviews with representatives from companies taking part in the original study and other retailers that are also using RFID. In total 25 companies responded to the online survey and 13 in-depth interviews were carried out.

The study found that the core business case identified in the 2018 study remained a consistent strategy adopted by most of the retailers taking part in this study – counting stock in physical retail stores with a handheld reader to achieve improved inventory accuracy. The primary justification remained the value this brought in terms of increased sales, reducing staff costs and stock holding, and in some cases, bringing down the value of retail losses. Beyond this, innovation was largely found to be incremental in nature and tightly bound by the need for a robust business case to be clearly present.

Executive Summary

Integrating RFID into Business as Usual (BAU)

The study found that as businesses become more established in their use of RFID-generated data, additional use cases are gradually added to their BAU practices. This included:

- Streamlining the Audit Process

- Improving Store Processes

- Utilising Smart Fitting Room and Magic Mirrors

- Broadening the Coverage of RFID

The Omni Channel Imperative

For all the companies taking part in this research Omni Channel retailing was now regarded as BAU and their investment in RFID was seen as a key facilitator in delivering this mode of retailing. This was evidenced through:

- Utilising Physical Stores as Fulfilment Centres

- Improving Online Order Accuracy

Supply Chain Utilisation

While most respondents stated that they were now using RFID in their supply chain, a number of those interviewed were cautious in the extent to which it could bring direct value in this environment. The main use cases were focussed upon checking the accuracy of inbound and outbound shipments and improving the accuracy of DC inventories. In addition, where DCs were being used as online order fulfilment centres, then RFID could bring value in the online ordering process (checking product availability, product finding, order accuracy etc). However, making a generalised business case for using RFID to monitor stock inventories in the retail supply chain was seen as challenging by several respondents.

RFID and Self-checkout

Only one retailer interviewed was currently using RFID to deliver a self-checkout (SCO) option for their customers. Its relative scarcity was due in part because of the need to have a 100% SKU tagging strategy in place and for the read reliability at the SCO to be extremely high. Any tags that were not automatically read could lead to a direct loss to the business. However, the use of RFID to facilitate SCO was found to deliver several benefits:

- Speed of Checkout

- Loss Control

- Customer Service Benefits

Facilitating Retail Loss Prevention

While none of the participating retailers argued that reducing loss was the primary reason for investing in RFID, many were now reaping more indirect benefits in this area:

- Tackling Refund Frauds

- Enabling Dynamic Product Loss Profiling

- Managing E-frauds

- Stolen Product Identification

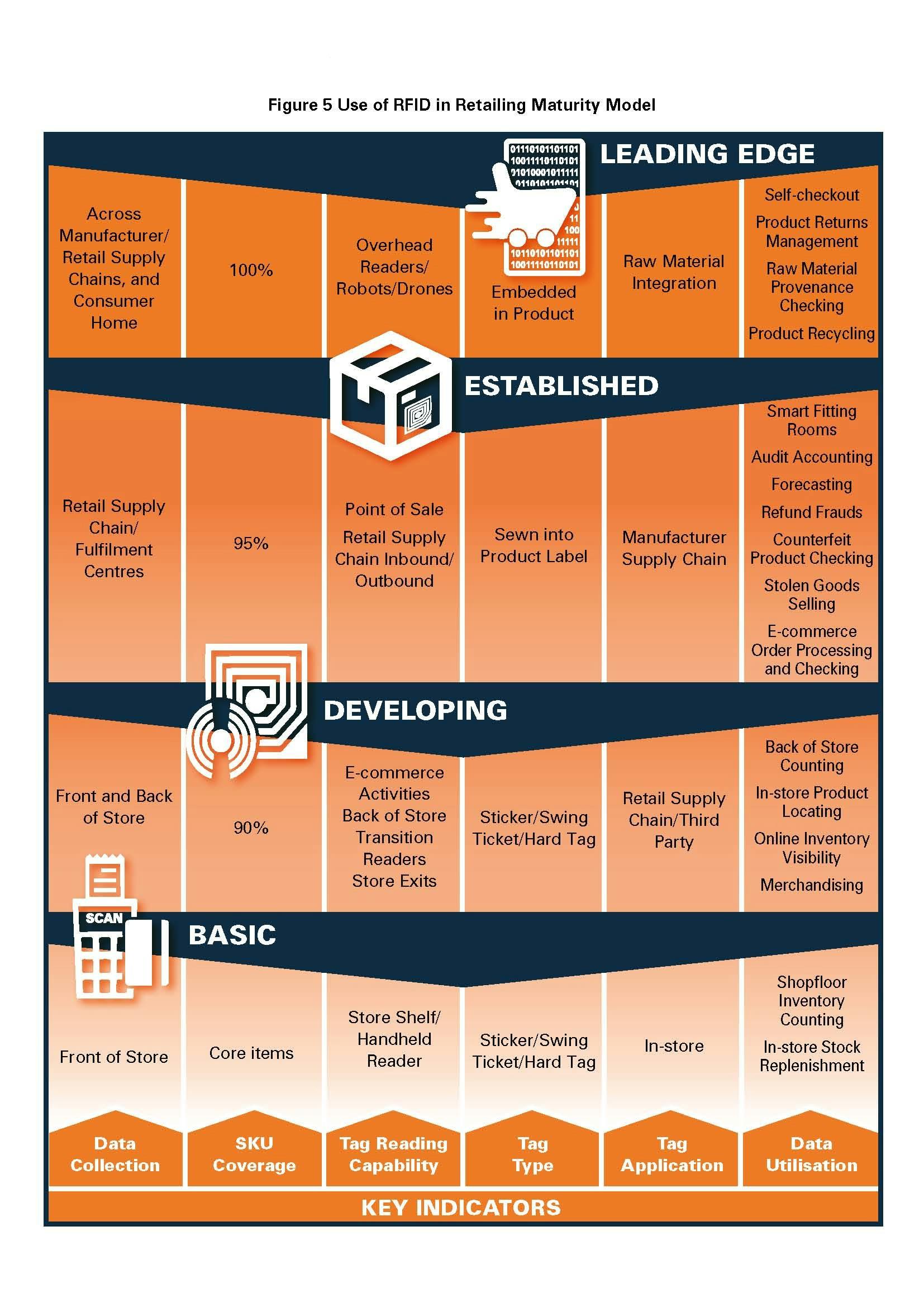

Use of RFID in Retailing Maturity Model

The research identified a range of stages of maturity in the way in which RFID is being used in retail environments, ranging from Basic and Developing approaches through more Established utilisation modes and on to what can be regarded as Leading-Edge use. However, it seems clear that the degree of utilisation of RFID in retailing can be seen for many adopters as an incremental journey – that as new business cases for its use emerge/become sustainable, then its use further develops.

Foreword

It is a great pleasure to introduce this latest piece of research from the ECR Retail Loss Group on how retail companies investing in RFID are growing and developing in the way in which they use this technology. As a Group, we have been reviewing the use of RFID since the early 2000s – it is certainly a technology that has a long history in retailing although, at times, it has been a rocky journey!

We are very grateful to Professor Beck for undertaking this study and bringing together the various ways retailers are innovating in the use of RFID to enable it to bring further value to their businesses. Very often, it can take some time for technology-based retail developments to realise their full potential – it can be a long and incremental journey – and, as documented by Professor Beck, RFID is no different. But, as we showed in the 2018 ECR Report on RFID, in the right circumstances, this technology can deliver concrete benefits through improving inventory accuracy and providing users with a source of valuable data to better inform their business strategies and working practices.

This latest research not only consolidates this view but also shows how some RFID users are now generating additional value from their investment – utilising the data in more retail settings and for a broader range of purposes. I very much hope that this report provides those thinking about investing in RFID with further insights on what it might be able to deliver, and for those already invested, how they might achieve even further benefits from this technology. As always, the ECR Retail Loss Group is extremely grateful to all those retailers that willingly contributed to Professor Beck’s study – without your active support we would not be able to produce these reports.

Finally, can I encourage you to not only read and share this study, but also take part in the work of the ECR Retail Loss Group – further details can be found at: www.ecrloss.com.

John Fonteijn

Chair of the ECR Retail Loss Group

Executive Summary

Background and Context

This report builds upon the findings presented in the joint ECR Retail Loss Group/GS1 UK Study published in 2018: Measuring the Impact of RFID in Retailing: Key Lessons from 10 Case-study Companies, which found a positive return on investment primarily based upon a simple strategy focused on retail stores and collecting data via hand held devices. The current study offers insights into how retail companies develop in the way in which they use RFID and the associated data – looking at what innovation looks like in this space, what the limitations are, and what benefits can be achieved.

It is based upon an online survey of retailers and interviews with representatives from companies taking part in the original study and other retailers that are also using RFID. In total 25 companies responded to the online survey and 13 in-depth interviews were carried out. Because of COVID-19 limitations, no research visits were possible to view RFID systems in action.

Findings

Intrinsic Value of the RFID Plateau of Productivity

The core business case identified in the 2018 study remained a consistent strategy adopted by most of the retailers taking part in this study – counting stock in physical retail stores with a handheld reader to achieve improved inventory accuracy. The primary justification remained the value this brought in terms of increased sales, reducing staff costs and stock holding, and in some cases, bringing down the value of retail losses. Beyond this, innovation was largely found to be incremental in nature and tightly bound by the need for a robust business case to be clearly present.

Integrating RFID into Business as Usual (BAU)

The study found that as businesses become more established in their use of RFID-generated data, additional use cases are gradually added to their BAU practices. This included:

Streamlining the Audit Process: the routinised and more manageably collectable nature of inventory data enabled by RFID meant that companies were now using it to replace their routinised but infrequent organisational stock takes undertaken for accounting purposes. This was delivering not only considerable savings in audit costs, but also providing more regular insights into the status of organisational inventories.

Improving Store Processes: greater stock visibility throughout retail locations was enabling some companies to reduce the problem of Pseudo Out of Stocks – stock not on the retail shelf but present in the back of the store. This was achieved through, for instance, the regular production of specific pick lists targeting this problem. Others were using RFID to improve the speed of stock searching in back-room areas, which helped considerably with Ship-From-Store Omni Channel activities. For another company, the RFID data enabled staff, via a bespoke App, to compile customer wish lists as they browsed the store.

Utilising Smart Fitting Room and Magic Mirrors: while these initiatives were still not commonplace amongst retail companies, some were now beginning to understand how to generate value from their introduction, particularly when their impact was measured more through customer satisfaction than direct profit improvement.

Broadening the Coverage of RFID: as companies mature in their use of RFID technology, the business case for tagging a larger proportion of SKUs becomes more persuasive. In addition, improvements in the applicability of RFID tags to a broader range of retail products and an overall reduction in their cost has further accelerated this process.

The Omni Channel Imperative

For all the companies taking part in this research Omni Channel1 retailing was now regarded as BAU and their investment in RFID was seen as a key facilitator in delivering this mode of retailing. This was evidenced through:

Utilising Physical Stores as Fulfilment Centres: without the inventory accuracy offered by RFID, few retailers believed they could reliably use their retail stores to fulfil online orders. For one retailer, this meant that only RFID-enabled store stock was made available for this purpose. For another retailer, utilising stores in this way also helped to increase inventory turn, reduce markdowns, and optimise the management of working capital.

Improving Online Order Accuracy: Where online orders are collated manually, errors can creep into the picking and packing process, generating customer complaints and increased returns. One retailer using RFID in their fulfilment process to cross check picked items against customer orders, claimed a 90% reduction in incorrect orders and customer complaints since introducing this process.

Supply Chain Utilisation

While most respondents stated that they were now using RFID in their supply chain, a number of those interviewed were cautious in the extent to which it could bring direct value in this environment. The main use cases were focussed upon checking the accuracy of inbound and outbound shipments and improving the accuracy of DC inventories. In addition, where DCs were being used as online order fulfilment centres, then RFID could bring value in the online ordering process (checking product availability, product finding, order accuracy etc). However, making a generalised business case for using RFID to monitor stock inventories in the retail supply chain was seen as challenging by several respondents.

RFID and Self-checkout

Only one retailer interviewed was currently using RFID to deliver a self-checkout (SCO) option for their customers. Its relative scarcity was due in part because of the need to have a 100% SKU tagging strategy in place and for the read reliability at the SCO to be extremely high. Any tags that were not automatically read could lead to a direct loss to the business. However, the use of RFID to facilitate SCO was found to deliver several benefits:

Speed of Checkout: because RFID does not require line of sight reading for product identification, it means that far more products can be registered at the checkout at the same time (bulk reading).

Loss Control: by automating the product recognition and registration process, it makes it considerably harder for errant users to non-scan items or mis-represent one product for another

Customer Service Benefits: an RFID-based SCO system significantly reduces the likelihood of double scanning, where a consumer inadvertently registers the same item for payment more than once. In addition, former checkout staff can be redeployed to more sales-driven activities on the shopfloor.

Facilitating Retail Loss Prevention

While none of the participating retailers argued that reducing loss was the primary reason for investing in RFID, many were now reaping more indirect benefits in this area:

Tackling Refund Frauds: by enabling products to be identified uniquely, RFID can be used to identify incidents where thieves are trying to return non-purchased products. While this is potentially a ‘game changer’ in responding to this problem, it does require an RFID system capable of interacting with an EPOS system, the RFID tag not to have been removed from the returning product, and a returns policy that clearly facilitates such as approach.

Enabling Dynamic Product Loss Profiling: lack of information about missing products is a perennial problem for loss prevention teams. What RFID data can do is offer greater insights into which products are more vulnerable to loss and, because of more frequent inventory checking, enable the performance of potential stock loss interventions to be more quickly and accurately assessed.

Managing E-frauds: When customers fraudulently claim an online order is incorrect, it can be hard for a retailer to refute. One retailer was using RFID-based data generated through their order checking process to provide evidence to challenge these claims.

Stolen Product Identification: For one US retailer, handheld RFID scanners were being used at Flea Markets and other Open-Air Markets to check the veracity of their products being offered for sale in these environments. The RFID data was analysed to understand the origin of the products and whether it had ever been ‘purchased’ through the business.

Plans for Innovation in the Use of RFID

The priorities for future use of RFID systems included: greater data integration; increased use in the retail supply chains; the utilisation of more forms of reader technologies; its application to SCO services; broadening the range of SKUs and locations where RFID was enabled; and the introduction and use of Smart Mirrors and Augmented Reality technologies.

RFID in Retailing

Use of RFID in Retailing Maturity Model

The research identified a range of stages of maturity in the way in which RFID is being used in retail environments, ranging from Basic and Developing approaches through more Established utilisation modes and on to what can be regarded as Leading Edge use. Most retailers taking part in this study could still be regarded as at the Basic and Developing Stage, with relatively few having a more Established profile and hardly any that could be considered as Leading Edge. However, it seems clear that the degree of utilisation of RFID in retailing can be seen for many adopters as an incremental journey – that as new business cases for its use emerge/become sustainable, then its use further develops.

What seems clear from this research and the earlier study completed in 2018, is that the overarching philosophy of ‘keep it simple’ and ‘make it pay’ still seems a sensible position to adopt when deciding whether to invest in RFID-based systems.

Background and Context

In February 2018, the ECR Retail Loss Group, in partnership with GS1 UK, published a study capturing the experiences of 10 retail companies that were at various stages in the use of Radio Frequency Identification technologies (RFID). The report, Measuring the Impact of RFID in Retailing: Key Lessons from 10 Case-study Companies, summarised the business context for the decision to invest, the various ways in which its impact was being measured and the value it was bringing, what lessons could be learnt from their experiences of utilising RFID in their organisations, and possible future developments they were planning2 . The study found that all 10 companies had achieved a positive return on their investment in the technology, particularly measured in terms of an increase in retail sales, driven by improved inventory accuracy which in turn had reduced the extent of lost sales caused by products not being available for consumers to purchase. In addition, some of the participating companies had benefited from being able to reduce the value of their stock holdings, reduce staffing costs and in some cases bring down the value of stock losses they were experiencing (shrinkage).

Overall, the report reflected a positive experience for retailers that operated in an environment that was conducive to the utilisation of RFID – primarily apparel, stocking product types that made the business case deliverable. In addition, the study found that most companies had adopted a relatively simple and focussed approach to how the data derived from the technology was being used and managed – almost exclusively collected in physical retail stores, mainly via handheld devices and principally driven by a desire to improve the accuracy and transparency of stock available on the shelf. This ‘keep it simple’ strategy had clearly delivered tangible dividends for these companies and articulated the importance of having a highly focussed laser sharp understanding of what the purpose of the technology was and how its impact and value would be measured and achieved.

While most of the companies had adopted this store-centric and defined approach to what the RFID technology would be used for, many also articulated potential plans for future developments – to begin to use the technology and data in different settings and for a wider range of purposes and possible business benefits. The purpose of this report is to consider how retailers have begun to utilise RFID-based technologies beyond the highly successful but closely defined business cases captured in the 2018 study. In particular, the study aimed to answer the question: how have retail companies developed (if at all) in the way in which they are using RFID and associated data – what does innovation in this space look like, what are the limitations, and what benefits can be achieved?

Methodology

The study adopted a two-pronged approach to gathering data to answer this question. First an online survey of global retail companies was undertaken to identify businesses utilising RFID in ways regarded as ‘innovative’3 . Secondly, interviews were carried out with representatives from some of the 10 companies taking part in the 2018 study and with other retail businesses identified via the online survey and from recommendations made by RFID technology provider companies. The online survey generated useable responses from 25 retail companies based in Australia, Europe, and the USA. Of the previous 10 companies taking part in the 2018 study, representatives from six were interviewed, of the remaining four, three were of the view that nothing had changed in the way in which the business was utilising RFID, and one could not be contacted. In addition, representatives from a further 7 companies were interviewed to understand how they were innovating in the use of RFID. In total, 13 interviews were carried out as part of this research – due to the ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic, all of these were carried out online. It was also not possible to visit any of the retail stores where the technology was in use – at the time of writing, the retail sector in many countries remains in various stages of lock down, with only online and essential stores operating in some.

Inevitably, given the significant and ongoing economic dislocation caused by the Pandemic, many plans for the introduction and development of RFID-based systems (and other investments) have been put on hold while retail companies understand and react to the consequences of the Pandemic. As with any study focussed upon the retail sector, there are limitations in terms of the representativeness of those agreeing to take part. Details of the online survey were advertised via business social media, sent to known contacts of the researcher and members of the ECR Retail Loss Management Group, distributed by the RFID Online Journal team to a list of their contacts4 , and circulated to customers of all the main suppliers of RFID technology. From these contacts, interviews were then arranged with those viewed as innovative and prepared to discuss their experiences with the researcher. As such the sample is self-selecting and limited (few companies where English is not routinely spoken made themselves available for interview). As such, caution needs to be exercised when reviewing the findings from this research.

Throughout this report, direct quotations are provided from the transcripts of interviews carried out with representatives from the companies taking part in this research. Each quotation has been given an identifying case-study number to anonymise the companies. The companies that participated in this research and agreed to be named are: Adidas; C&A; Decathlon; Harvey Nicholls; Kurt Gieger; Lululemon; Marks & Spencer; River Island; Stadium; and Brunello Cucinelli. In addition, Peter Longo, a former President of Macy’s Logistics and Operations and a member of GS1 US’s Board of Governors also provided valuable input.

The terms RFID, RFID system and RFID technologies will be used to describe a system whereby some form of uniquely identifiable taggant is attached to a retail product, which can then be identified using a range of different Readers, which in turn communicate with a software system that is able to recognise, record and where appropriate associate that taggant with other retail data. While there are numerous variants of this system, the basic elements remain consistent: some form of tag (typically representing a Unique Product Code (UPC)), a variety of readers to identify the tag (via Radio Frequency and Line of Sight) and a software system to offer the capacity for collation, connection, visualisation, and analysis.

The Report is made up of three sections: the first provides the context and background to the study. The second maps out the findings from the online survey and the interviews, and the third draws together the main conclusions from the study, including a Maturity Model summarising the way in which RFID is being utilised in the retail sector5 .

Findings

The data from the online survey and the interviews with respondents identified several areas where the use of RFID technologies had developed beyond the core area of counting stock in physical retail stores using handheld readers, although this remained a dominant focus for all businesses, as will be discussed below. Five key areas emerged from the data. First, developments in the way in which RFID was becoming integrated into systems and operations, and increasingly viewed as Business as Usual (BAU). Secondly, enabling the delivery of omni channel retailing, including Buy online and Pickup in Store (BOPIS); Ship From Store (SFS); and reducing Buffer Stock Margins (BSMs). Thirdly, the use of RFID in the retail supply chain, particularly distribution centres (DCs). Fourthly, how RFID innovation is contributing to the management of retail losses, and finally, RFID and Self-checkout systems. Each of these areas will be considered below, but the section will begin with a review of the overall use of RFID found in this study by the retailers participating in this study

Intrinsic Value of the Plateau of Productivity

While the focus of this study is directed towards exploring how retailers are innovating in the use of RFID technologies beyond the primary scenario detailed in the 2018 study – counting stock in physical retail stores with a handheld reader, it quickly became apparent that there were relatively few retailers that had substantively moved beyond this use case to any great extent. Part of the reason for this was the challenge of developing business cases to justify its use. As one respondent put it:

We probably use 5% of RFID’s capability …there’s lots of talk, plans and aspirations in the industry for what RFID can do but not a lot of evidence thus far. It is very difficult to come up with a [standalone] business case beyond the core purpose of RFID – counting stock on the shelf and the back of the store[RR2].

Another respondent agreed, arguing that getting beyond this use case can be difficult: ‘RFID is a challenging technology to get to work well in a retail environment’[RR7]. For others, especially some of those companies that had taken part in the 2018 study, they were still on a journey of integration which was viewed as a necessary stepping stone to the future expansion in the use of the technology: ‘[we are still]…trying to merge all the data systems into one version of the truth’[RR1]; ‘Serialised numbering is the core of the concept and it must be interoperable – we are not there yet’[RR9].

The challenge of pushing the RFID ‘envelope’ was particularly apparent in efforts to use overhead readers in retail stores, seen by some commentators as a way to remove the need for staff to scan stock using a handheld reader, and provide a continuous view of a store’s inventory position. Two of the retailers interviewed for this research had piloted this technology and both had experienced challenges in making the business case persuasive.

For one it was the cost and complexity: ‘So decided to park the project for now – the business case was not the most rewarding – the costs associated with this are enormous’[RR2]. The other retailer held similar views: ‘The real issue is the amount of readers you need and the cost; hard to get the payback in a reasonable time… it was still very complicated to get the data accuracy that would make it worthwhile’[RR4]. Both recognised that while in theory the use of overhead readers makes sense and could well be part of future iterations, the problems associated with maintaining data accuracy can become overwhelming:

We thought all these issues would be manageable, but it was hard to get certainty about the status of all items in a store. We tried to get workarounds, but it became very complex and too many things can go wrong in a store – you also rely upon everybody doing the right thing all the time. So, the system begins to drift every day, just a little bit, but that quite quickly grows to a level whereby you need a full store count to establish where you are and fix the discrepancies[RR2].

Once again, the issue of ROI and value-added dominated thinking and decision making – what extra value can be attained from adopting this approach and is it manageable? Certainly, in the near term, the use of overhead readers in retail stores would seem to be an innovation that has yet to be fully embraced by the retail RFID user community

Integrating RFID into Business as Usual

While overhead readers were an example of an innovation which for the most part are still waiting to happen, the research uncovered other ways in which businesses were beginning to extract additional value from their investment in RFID. This was evidenced in the following ways7 .

Streamlining the Audit Process

Routine stock audits have been the bedrock of most retail operations, partly as a legal necessity in some countries to enable accounting practices to be satisfactorily ratified, but mainly to ensure a business has a better understanding of their inventory – what stock do we have and where is it? Auditing practices vary considerably – for many companies it will be an annual event and could be completed in-house or by a specialist auditing company. For some it is a purely financial exercise – calculating the value of the stock in the business, while for others it can be a SKU-based count – how may items of stock do we have? Either way, it can be an expensive and time-consuming exercise although the benefits can be considerable8 .

For several companies taking part in this research, RFID was now playing a key role in streamlining this process, making it easier and cheaper to complete, and therefore an activity that could be undertaken more often. Indeed, for some the ‘annual’ stock take had now been abandoned as their routine RFID-based stock counts were regarded as a better way to provide the data for accounting purposes and improving the accuracy of their inventories. As one respondent summarised it: ‘[we have achieved] significant saving on stock taking; increasingly making annual stock takes redundant’[RR4]. For another, while it had taken time for the business and the tax authorities to build confidence in the efficacy of the RFID data9 , they were now seeing a significant saving in annual stock audit costs: ‘year on year we are saving a seven-figure number – it was never part of the original business case for RFID, so a good development for us’[RR10].

Improving Store Processes

RFID technologies are essentially a means to generate precise and unique data on retail stock, such as its identity (sizing, price, colour etc), location (on a shelf, back of store etc) and status (sold or not sold). While this data is key to driving the core objective of improving inventory accuracy, several companies are now innovating in how this data can further improve business activities. For one company, it was being used by store teams to reduce the incidence of pseudo Out of Stocks (OOS): ‘Now producing pick lists twice a week for stock that is in the stockroom but not on the shopfloor’[RR2]. For another, RFID was enabling much quicker stock search and find tasks, particularly in larger stores with extensive back-room areas. As will be discussed below, this can be an important feature in developing an efficient Ship from Store (SFS) capability: ‘RFID enables search and find to be easier – the Geiger counter approach – important when you have large stores and backroom areas’[RR2]. For a retailer trading in very high value products, the RFID data was now being used by staff, via a bespoke App, to build customer ‘wish lists’ as they browsed products, enabling them to provide an even higher level of customer service.

Smart Fitting Rooms and Magic Mirrors

While the concept of the ‘smart’ fitting room and ‘magic’ mirror have long been associated with RFID in retailing, they were still a relative rarity amongst the companies taking part in this research10. Once again, issues around ROI were raised and their implications for staffing and customer service: ‘Smart fitting rooms sound like a good idea, but they have significant implications for staffing and customer expectations – have you got enough of one to satisfactorily and consistently meet the needs of the other?’[RR14]. For another retailer they were adopting a relatively straightforward approach to the use of the RFID data around their fitting rooms: ‘Trial underway – simply displays the number of items a customer is carrying in to the changing room’[RR2]. Only one company was beginning to roll out what might be regarded as a combination smart fitting room and mirror, but again their experience had been challenging:

Now have a smart fitting room that is scalable which reads the tag regardless of where the customer holds it – this is the only consumer facing RFID product we have developed so far. It was not easy – had to work with three providers – hardware, software, and technology reader. The rationale is to save time for the consumer, but you must educate the consumer to use this technology[RR3].

In this case, measuring the value of the investment was not based upon any impact upon sales (too hard to generate causative data) but more through customer satisfaction via a Net Promoter Score (NPS). Using this measure, the retailer claimed that the smart fitting room scored the highest NPS of any of their current customer-facing digital tools.

RFID Penetration

Another area of innovation with regards to how RFID was becoming embedded into BAU was in the expansion of the breadth and range of SKUs and retail locations where it was being used. RFID technologies have had a long and chequered history when it comes to their application on objects which are predominately metal and/or contain viscous fluids. As the 2018 ECR Report identified, this had led most companies to only tag a proportion of their products, excluding those items that were too hard to tag or where it did not make financial sense (the tag cost was proportionally too high). However, the downside of this approach is that companies must maintain different data systems to manage products with and without an RFID tag.

What was evident from the current study was that many companies were pushing forward to increase the number of SKUs which were RFID enabled. This was partly driven by a more favourable business model: ‘Cost of RFID has come down which makes it more cost effective to use on a broader range of products and the business case does not have to be as robust as in the past’[RR2]. But it was also the case that different types of tag were being utilised to make more SKUs RFID compatible, with several companies actively exploring/ now adopting a strategy where the RFID tag is either sewn into the product care label or fully integrated into the product itself. As will be discussed below, for one company, getting to 100% of SKUs RFID tagged was an essential part of their strategy to deliver self-checkout, but it can come at a considerable cost: ‘Getting to 95% of SKUs was fairly easy but the last 5% for us was very expensive’[RR9].

The Omni Channel Imperative

There is no doubt that the COVID-19 Pandemic has wreaked considerable havoc across the global retail industry, driving many well-established brands into bankruptcy, such as the Arcadia Group of businesses11. It has also seen a massive expansion in the volume of online sales as locked down consumers have had little choice but to shop from home. While E-commerce has been growing steadily in many countries over the past 10 years as a proportion of total retail sales, with many retailers adopting a twin track approach of both physical retail stores and an online presence, the Pandemic effectively closed the former and rapidly promoted the latter, certainly in the short term12. It is highly likely that consumers will want to return to physical stores once Pandemic restrictions are removed – they will remain a significant cultural and social setting for many years to come, but the days when a retailer operates exclusively through this format are likely to be increasingly limited or restricted to only a small number of retail formats where an online option is considered unviable13.

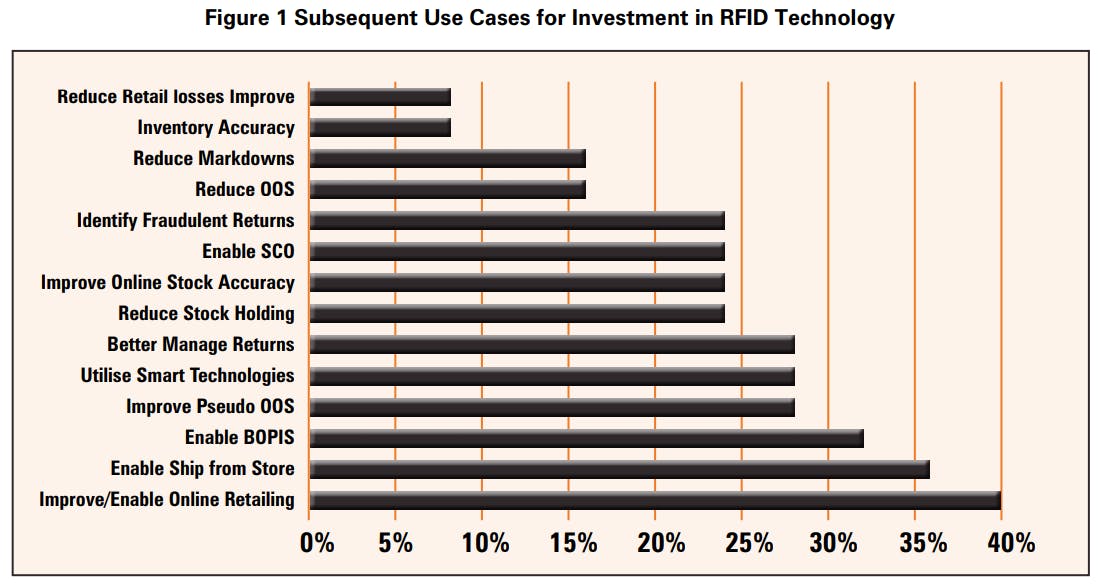

For all the companies taking part in this research, omni channel was now BAU and their investment in RFID was increasingly seen as a key facilitator in delivering this mode of retailing. As one respondent put it: ‘We need to future proof the business and therefore we need a proper omni channel strategy’[RR8]. This was evidenced in some of the data collected through the online survey of retailers. While improving and enabling online retailing was the fifth most popular primary use case for initially investing in RFID, it accounted for the top three subsequent use cases (Figure 1).

As can be seen, Improving and Enabling Online Retailing was the most frequent use case selected, followed by Enabling Buy Online Ship from Store (BOSFS) and Enabling Buy Online Pickup in Store (BOPIS). Respondents’ views were driven by growing awareness that fulfilling online orders requires much higher levels of stock accuracy throughout a retail business – in effect an Enterprise View of Inventory (EVI) where stock held in all retail locations is accurately recorded and identifiable14. For one respondent, this need for stock accuracy was driven by customer perceptions of the online shopping experience: ‘Studies have shown that customers are more tolerant of inconvenience and out of stocks when visiting a physical store than when shopping online’[RR6].

RFID Enabling Stores to be Used as Fulfilment Centres

For several respondents, their investment in RFID to generate significantly higher levels of inventory accuracy was pivotal in the business deciding to begin to use physical stores as online order fulfilment centres: ‘Without RFID, it would be hard to use the stores as fulfilment centres – just too unreliable; inventory accuracy would be too low without RFID’[RR1]. Another respondent made the same point: ‘In order to build the confidence that the stores could do this [E-commerce fulfilment], because they traditionally have very poor inventory accuracy, they had to be improved and the only way was the use of RFID’[RR6]. For a third respondent, whether a SKU was part of their RFID programme determined what products could be shipped from a physical store: ‘It is a very labour-intensive process [fulfilling online orders], particularly the picking process, so we only do BOSFS with RFID products because accuracy isn’t good enough with non-RFID products’[RR2].

In addition to helping to fulfil online orders, one respondent also reflected on the value this process can bring to the business in terms of making physical stores more profitable:

Large [Department] physical stores have low inventory turn – average would be 2.1/2.3. So, the average item hangs around a store for about 180 days. Omni channel speeded up turn and reduced markdowns; optimised working capital management[RR6].

Improving Online Order Accuracy

One retailer had recently begun to use their RFID capability to improve the accuracy of their online order fulfilment process. While several retailers are now exploring and using automation in the product picking process in bespoke online order fulfilment centres, for most, the selection and distribution of products remains a largely manual process completed by humans. Inevitably, this can lead to errors with consumers not receiving the products they have ordered. For this retailer, RFID was being used to enable a check of the accuracy of the picked goods against the original order to be carried out: ‘All e-comm orders use RFID – there is a check on Outbound to make sure the product pick matches the customer order – this has led to a massive reduction in claims for incorrect orders and complaints – number has dropped by at least 90%’[RR3]. In this scenario the online order package is passed through a RFID Reader Tunnel that compares the product data against the customer order. In addition to reducing the number of customer complaints and returns, the retailer also believes that the data checking process provides a useful data point to challenge possible cases of customer fraud: ‘[It] helps to challenge fraudulent claims by customers for nondelivery – evidence point to use with customers’[RR3].

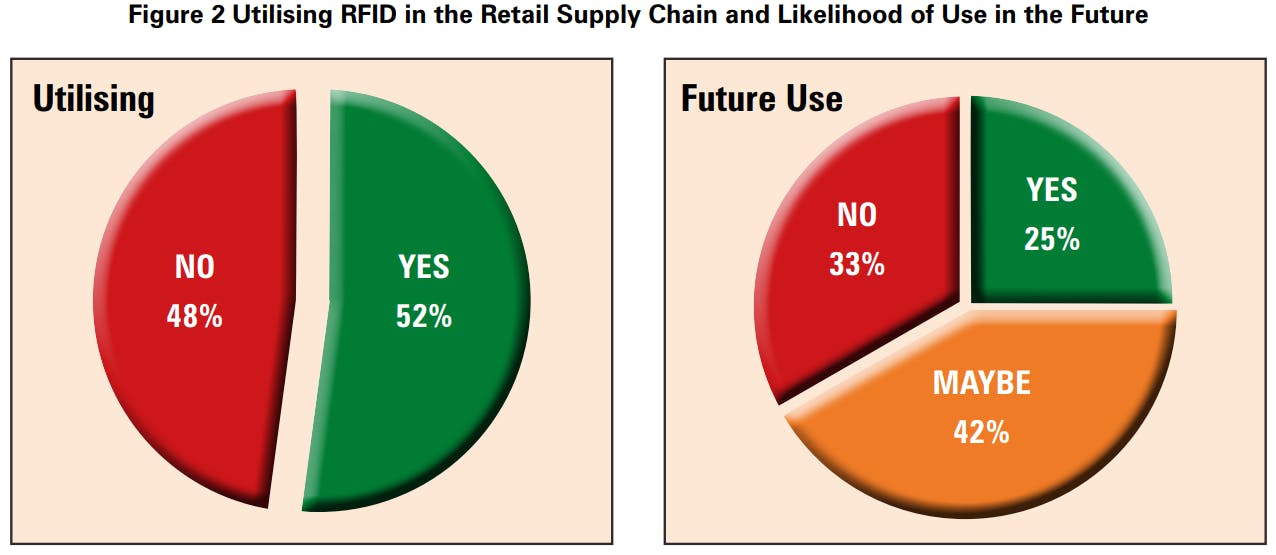

Supply Chain Utilisation

In the 2018 ECR Report, respondents were asked what their plans for the use of RFID were and the second most popular response was to begin using it in their retail supply chain. As can be seen in Figure 2 from the online survey, just over one-half of respondents (52%) said that they were now using RFID in some way in their retail supply chain, while one-quarter of those who were not currently using it thought they might in the near future.

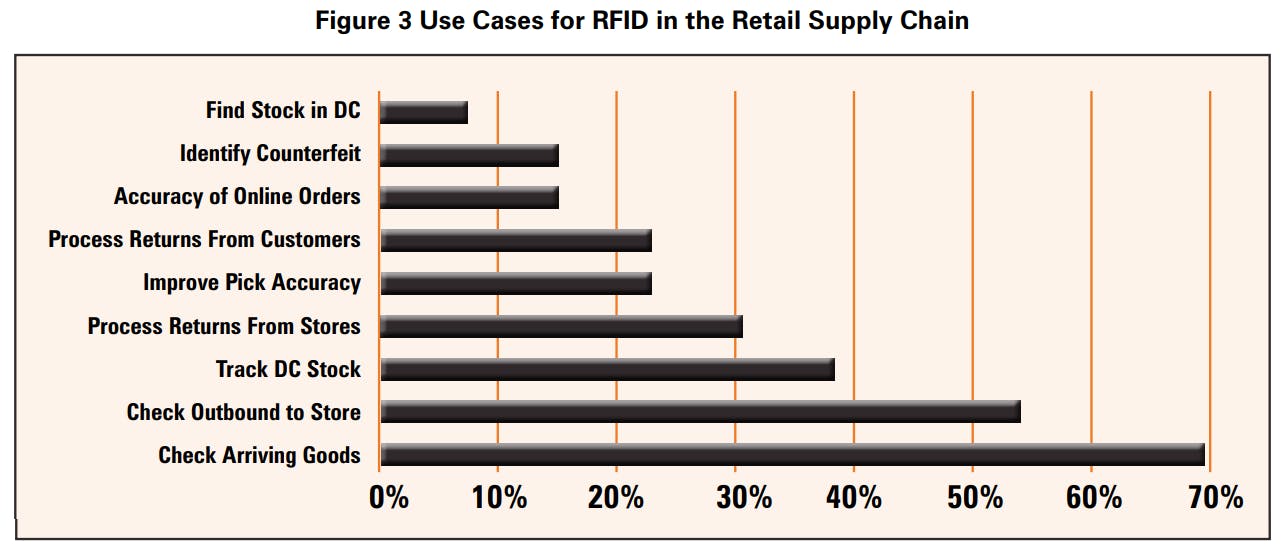

When respondents were asked to describe how RFID was being used in the retail supply chain, a range of use cases were described (Figure 3).

By far the most common use for RFID was checking the veracity of goods arriving at DCs, with nearly 70% of respondents selecting this option, while the second most common response was checking the accuracy of SKUs destined for retail stores: ‘We have automated our distribution centres – packages move from inbound lorry on a conveyor belt through an RFID tunnel; do the same for outbound to the stores and third party’[RR3]; ‘We are scanning items out of the DC sent to retailers to check orders – number of items to be shipped’[RR10]. The third most common use of RFID in the retail supply chain was for monitoring stock accuracy in DCs, followed by processing returns from retail stores. Other options chosen by respondents included processing returns from customers, monitoring pick accuracy and processing of online orders (as discussed earlier), locating stock in DCs and identifying stock that is counterfeit.

Challenges of Making the Business Case

While the online survey identified some of the ways in which companies were utilising RFID in their supply chains, several respondents interviewed expressed issues about the difficulty of making the business case to begin using it in this environment. Of particular concern was the challenge of identifying the problem RFID would resolve and whether it was the most appropriate intervention to address it. One respondent neatly summarised this issue:

Need to make sure there is clarity about what problem you want RFID to solve in the business. Why would you want to use it in the supply chain – what value added will it deliver? In some cases, there may well be another means or approach that could be more successful[RR2].

Other respondents echoed this sentiment: ‘Warehouse team have not been pushing to use RFID – do not think it would add to their efficiency – would cost millions to put the technology into the supply chain and so cannot see the ROI’[RR1]; ‘The warehouses don’t need RFID – they are already well organised and largely automated – no business case for using it’[RR6].

RFID and Self-checkout

Perhaps one of the most dramatic developments in retailing in the last 10 years has been the phenomenal growth in the use of a range of self-checkout technologies (SCO)15. Regarded in the early part of the 2000s as a rather niche and glitchy technology unloved by consumers, for many grocery retailers, it is now on course to account for as much as 80% of all customer transactions in the next few years. This incredible growth has been driven by two main factors – the considerable cost savings retailers can achieve through its introduction, primarily labour costs, and significant improvements in the quality, reliability, and usability of the technology. For the most part, consumers have largely accepted this fundamental change in the way in which they checkout and pay for the goods they wish to purchase, often perceiving it as speeding up the process and for some, enabling them to avoid social interaction16.

While SCO technology providers are always keen to highlight the significant upsides of their wares, recent evidence from a growing range of retail users is indicating that these systems can also generate considerable losses as well17. Perhaps unsurprisingly, retailers are finding that consumers using these systems are not always wholly reliable, accurate or indeed honest in the way in which they use them. Indeed, a recent study by the ECR Group found that non-scanning of items, mis-scanning (misrepresenting one item for another) and walking away without paying was generating considerable losses18. In response to these problems, retailers are increasingly investing in a range of strategies and technologies to try and address them, including video analytics, adapting staffing levels and training, changes to store design and process improvements.

Only one of the respondents to this research had embarked on a SCO programme that utilised their RFID technology. Probably the main reason why this is the case is that for an RFID-enabled checkout system to work, it requires a comprehensive SKU tagging strategy to be in place: ‘It required 100% of products to be RFID – very difficult to explain to a customer to use different processes for different products based upon whether they have an RFID tag or not’[RR9]. This is certainly true – it would be unworkable to expect a consumer to know to scan some items with a barcode reader while for RFID-enabled products it would be done automatically through an RF reader located at the checkout. In addition, because of the criticality of read accuracy at the point of payment, the system must be extremely reliable and robust. Each item not scanning potentially generates a direct loss to the business, unlike errors generated when using RFID to check inventory accuracy for instance, which will be disappointing, but not necessarily directly loss making. For most retailers, this is inevitably an expensive proposition: ‘Being 100% accurate is 10 times more expensive than being 99.5% accurate’[RR9]. It is perhaps understandable, therefore, why few retailers of any scale have currently installed SCO systems that interact with their RFID-based technologies.

Potential Benefits of RFID-Enabled Self-checkout

While it is currently a daunting proposition to get to a position where SCO systems can be used in conjunction with RFID, when it can be done, if certainly offers some attractive advantages.

Speed of Checkout: because RFID does not require line of sight reading for product identification, it means that far more products can be registered at the checkout at the same time (bulk reading). Consumers simply need to place all the items they wish to purchase within a designated read zone and the system will do the rest. This is clearly much faster than traditional forms of SCO where the consumer must find and then scan the barcode of each item they wish to purchase. In turn, this should mean a much quicker throughput of shoppers, reducing queue time and potentially the number of checkout stations required19.

Loss Control: by automating the product recognition and registration process, it makes it considerably harder for errant users to non-scan items or mis-represent one product for another. It may still be possible to try and pass an item around a RFID ‘read zone’, but it is likely to be much harder to do this in ways that do not attract the attention of SCO supervisors. In addition, the payment process can be combined with deactivation of exit alarm functionality, making walkaway thefts less easy to perpetrate as well.

Customer Service Part One: In addition to speeding up the checkout process, an RFID-based SCO system also significantly reduces the likelihood of double scanning, where a consumer inadvertently registers the same item for payment more than once20. With each product having a unique identification code, its status as either not registered for payment or registered for payment will be readily apparent. While retailers have certainly benefitted from consumers double scanning (getting paid for the same product more than once!) it can be a source of consumer dissatisfaction when they subsequently realise what has occurred (they may feel that the system is cheating them which could generate future retaliatory deviant behaviour).

Customer Service Part Two: For the retailer taking part in this research that was using their RFID system to deliver SCO, a significant benefit they recognised was their ability to move staff from checkout duties to inaisle product sales advising: ‘[Self-checkout] has enabled the company to increase the number of hours staff spend on the sales floor to assist customers … when people get advice, they tend to buy more expensive products – staff add value’[RR9].

RFID and Self-checkout: Beneficial But Challenging

The experience of the retailer utilising RFID to deliver SCO was clearly very positive and in many respects a culmination of more than 10 years of investment, development, and integration of RFID into the very fabric of their business. As the retail industry begins to grapple with the loss consequences associated with a SCO focussed strategy, then the attractions of an RFID-based approach would seem self-evident. But, and it is a very big BUT, for those parts of the retail industry where SCO is most widely used – Grocery – then getting to the point where ALL SKUs are reliably and consistently recognised with some form of RFID taggant is an extremely daunting and expensive proposition at the moment – fast moving low value items are currently not the intended recipients of an RFID tag.

Indeed, it is interesting to note how most technology developers in the field of SCO are presently not looking at how RFID can be utilised for product recognition in this environment21. However, in other parts of the retail sector where RFID is much more prevalent and longstanding, such as apparel, then RFID-driven SCO could well be an attractive proposition as businesses mature in their use of the technology and the business case is made for a more frictionless retail consumer experience22.

Facilitating Retail Loss Prevention

The final area of innovation this study identified related to the use of RFID for retail loss prevention purposes. Like the study published in 2018, none of the retailers contributing to this research argued that reducing loss was the primary reason for investing in RFID: ‘Security was never even close to be a primary purpose for RFID’[RR6]. Indeed, a number raised issues with using it for this purpose at all or to act as a replacement for an existing Electronic Article Surveillance (EAS) system: ‘For us, it is not a substitute for EAS – paper tags can be pulled off; the POS system needs to be able to update the EAS system in real time … means we cannot use offline tills, have slow networks etc as this could cause false arrests’[RR2]. For another participant, the challenges of their EPC repository having the capacity to respond quick enough to the requirements of EAS at exit gates was also an issue: ‘If you use RFID for EAS then its capability to access the EPC repository needs to be fast – within the range of 400 milliseconds’[RR8].

But, there were four areas where RFID was identified as facilitating the management of retail losses in some of the companies taking part in this research: refund frauds; loss profiling; E-commerce frauds; and stolen product identification.

Tackling Refund Frauds

Thieves undertaking refund frauds typically rely upon a key ambiguity to successfully perpetrate their crime – a retailer’s inability to categorically know whether an item presented for a refund has ever been purchased in the first place. In many respects refund fraud is one of the easiest ways to commit retail crime – genuinely purchase an item and get a receipt, return to the store, and take another item matching the description on the receipt from the shelf and present it for a refund. Store staff will assume that the product is the same item as described on the receipt and therefore issue a refund. The thief then gets to keep the original product for free. The fundamental flaw is that the SKU code does not uniquely identify each individual product, but merely offers a descriptor of what the product is to enable a price look up and trigger adjustments to the inventory.

What RFID offers is a way of identifying every single item to which a tag is attached, for instance, each size 10 blue dress is uniquely identifiable. This in turn enables each product’s status to be identifiable – has it been sold or not? For dealing with refund frauds, this is a real game changer – when the thief in the above scenario presents the second item for refund offering a receipt associated with another item that looks the same, the system will know that the product being presented for refund has not been sold thus far – the receipt is associated with another uniquely identifiable product, but not this one. Indeed, the data will enable staff to have access to a wealth of information about the product that has been previously sold – where it was purchased, when and how payment was made. In theory, this makes refund fraud extremely hard to carry out – the thief’s powerful weapon of ambiguity has effectively been neutralised.

Given this impressive capability, it is perhaps somewhat surprising that only two of the companies interviewed for this research were actively utilising this functionality of RFID. There are several reasons why this may be the case. First, some companies remove the RFID tag at the point of purchase either for privacy reasons or because it is in the form of a hard tag – this inevitably leaves open a degree of ambiguity about products being presented for refund – the would-be thief can remove a soft tag and claim it was previously purchased, although in the case of a hard tag, this would be more challenging without access to a deactivator.

The second more significant challenge is that the RFID system must be fully integrated into the POS system, something which only a minority of companies had done. Without this, the paid/not paid ‘status’ of unique products cannot be managed and therefore a thief’s weapon of ambiguity can be utilised once again. Thirdly, company policies around how refunds will be managed need to be aligned with the RFID capability of unique product identification. For some retailers, a relatively relaxed and laissez faire approach to customer requests for a refund has been regarded as an important part of their organisational identity, and so changing this to address the issue of refund frauds may be regarded as inappropriate. In such circumstances, understanding the ‘size of the prize’, the cost of refund fraud to the business, is undoubtedly an important statistic to be calculated if a business case for utilising RFID for this purpose is to be made.

Enabling Dynamic Product Loss Profiling

One of the greatest challenges of managing retail losses is the lack of product-specific information available from the main source of data on this subject – annualised stock inventory audits23. Because of the relative cost of undertaking audits, large swathes of the retail sector carry them out infrequently, meaning that timely information on product losses is rarely available. It also means that the impact of interventions designed to reduce losses can be hard to evaluate – the time lag between introduction and measurement can be considerable24.

Because of the capacity to carry out much more frequent and product-specific stock audits – most companies responding to the online RFID survey were performing them fortnightly or more frequently – data on losses is much more readily available: ‘Use RFID data to build patterns and trends on levels and types of loss in our retail stores’[RR2]. Other agreed, including the capacity of RFID data to make the use of security interventions more focussed: ‘It [RFID] provides information on what products are being stolen and we can then target them with hard tags’[RR9]; ‘The benefit to security is the information it provides to change the way in which product is protected’[RR6]. In this respect, RFID is enabling rather than driving retail loss control – it is instructive rather than having a direct impact.

Managing E-frauds

As with refund frauds carried out in physical stores, some forms of E-commerce frauds also rely upon ambiguity as a means of perpetration – in this case questioning the validity of the products delivered compared with those that were ordered. In this scenario, a fraudster claims that some or all the items ordered had not been shipped – errors had occurred in the picking and packing process. For one of the retailers taking part in this research, they had begun to use their RFID-based order shipping check process data (automatically comparing the items being shipped against the customer order) to challenge customer claims – offering evidence that the package contents were correct at the time of shipment25. While this process step was aimed primarily at reducing errors to reduce the rate of returns and customer complaints, it also had potential for beginning to address the issue of E-commerce frauds.

Stolen Product Identification

The final area of innovation in the use of RFID for retail loss purposes was in the identification of products that may have been stolen and were now being presented for sale at flea/open air markets. As part of an initiative to tackle Organised Retail Crime (ORC)26, one US retailer was using RFID to ascertain the status of products that their investigation team were finding in these locations. Using a handheld scanner, they can better understand the background of the products found – whether they had ever been paid for and where they had been last registered in the retailer’s supply chain (assuming an RFID tag was still on the product). Once again, like tackling refund frauds, the unique serialisation of retail products, provides a data window not previously available from a SKU-based numbering system.

RFID: Facilitating Loss Prevention

While the 2018 ECR Report on RFID identified a couple of retailers that were actively utilising RFID to manage retail loss using exit readers, most expressed concerns about the accuracy of read rates and the general fallibility of swing tickets/stickers to deter would-be thieves. The latest report found similar reservations about using RFID as an active security intervention – RFID exit readers remain a challenging technology to deliver high levels of accuracy. But, more retailers are utilising RFID data to augment and inform their loss prevention strategy – facilitating the process through providing a richer seam of data on product status and location.

Plans for Innovation in the Use of RFID

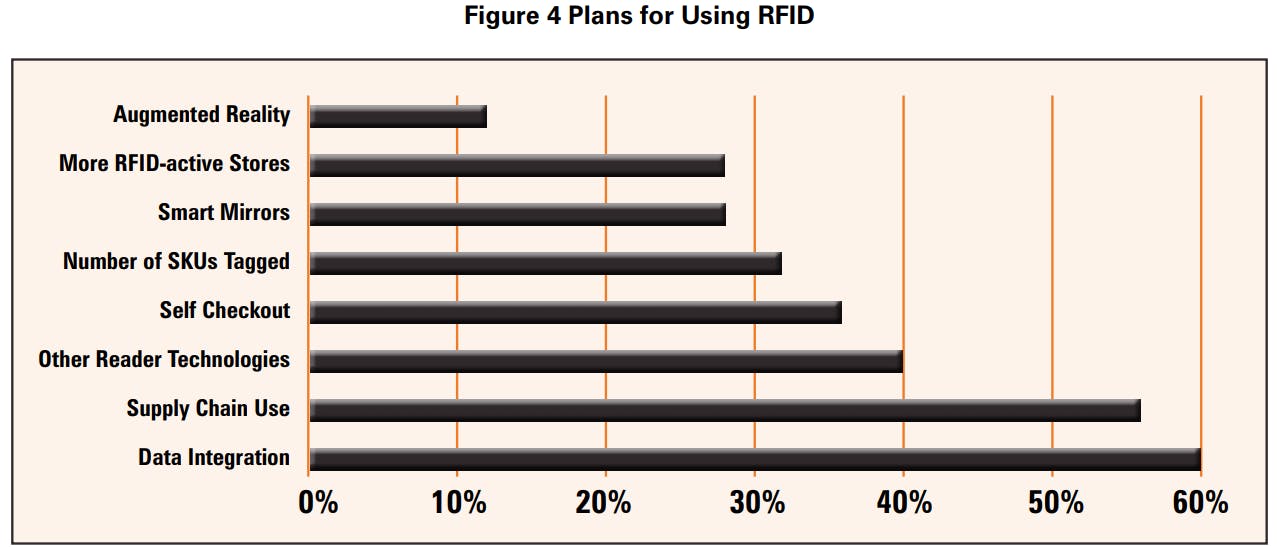

Like the 2018 report, the online survey also asked respondents to describe their plans for innovating in the use of RFID in their businesses (Figure 4).

The data is strikingly like that found in the 2018 report. The most common response was to innovate in the way in which RFID data is integrated into the business. This report has highlighted the way in which RFID has increasingly become BAU for those that have invested in the technology for some time, albeit still relatively focused upon the physical retail store. As the technology becomes more established, then opportunities for extracting value from the data would seem to be a clear future priority: ‘90% of the cost of an RFID project is the tag – so you only have to find another 10% to begin to utilise the tag’[RR9].

The second most common proposed future development was to utilise RFID in the supply chain. As detailed earlier, understanding the purpose of using RFID in a retail supply chain needs to be firmly established – what value added will it bring and at what cost are important questions. These two options were then followed by plans to use other forms of reader technology, such as transition and POS readers. No doubt overhead readers will remain on the horizon for some – they are a logical progressive step – but operationalising them would seem to present significant challenges in the short to medium term (as discussed earlier). Other plans also included using RFID for self-checkout – again, offering significant opportunities, but requiring a step change in tagging density and accuracy for many, and Smart Mirrors/Augmented Reality, and generally extending the range of products tagged and locations in which the technology was in operation.

Conclusions

Maintaining the Productivity Plateau

This project set out to build upon the findings of the 2018 ECR Report that focussed upon summarising the experiences of 10 retail companies at various stages in the implementation and use of RFID systems. The overall conclusion was that they had all achieved a positive ROI, utilising the technology to achieve a range of business goals and for the most part, following an operational maxim of ‘keep it simple’. While the RFID industry is always keen to espouse innovation, offering new ways to read tags and utilise the data, most of these retail companies had initiated a straightforward system focussed primarily upon regularly counting stock in the front and sometimes rear of their physical stores for the purpose of improving inventory stock accuracy. For many this level of utilisation represented a valuable and achievable plateau of productivity for their investment.

Revisiting many of these companies three years later, as well as reviewing the experiences of several other retail businesses utilising RFID, what seems clear is that while there are several examples of innovation in the way in which the technology is being used, what is striking is how few have moved much beyond the Plateau of Productivity described in the 2018 Report. The essential premise of using RFID to improve the accuracy of stock inventory records in physical retail stores via the use of handheld readers remains the dominant business case – the Innovation Uplands remain a rarely visited locale for many retail businesses interested in RFID. The research did, however, identify some key areas of innovation and how they could add value within specific retail contexts.

The Value of Unique Product Identification (UPI)

While the term RFID is frequently used as a catch all acronym to describe a system of uniquely identifying retail products and capturing that information via radio frequency waves, it should increasingly be viewed as being made up of two distinct components – the unique serialisation of products (ID) and a vector by which it is communicated, in most cases thus far, via radio frequencies (RF). But other vectors are also in use – one retail company taking part in this research was using a 2-D printed barcode to ‘transmit’ product ID to enable their programme tackling refund frauds to operate – their current POS was not capable of communicating via RF. In another case, a company is experimenting using Bluetooth to transmit product ID as a way of addressing some of the well-known operating challenges of RF27. While RF currently continues to be the vector that offers the most cost-effective way to achieve appreciable benefits in the retail sector, it is worth recognising that the real value is in the ID component – the unique identification of product that enables a wide range of data-driven opportunities to be garnered. In this respect, innovative progression was found to be largely focussed upon a growing maturity in how and to what purposes this data could be used.

Enterprise-wide Inventory Visibility – BAU and the Omni Channel Imperative

This was especially evident in one of the key ways in which companies were innovating in their use of RFID – enabling businesses to operate as omni channel retailers. Irrespective of the Pandemic-driven acceleration, online retailing has been steadily growing as a proportion of retail sales in many countries for several years. Beyond online only retailers, making this form of operation profitable for traditional ‘bricks and mortar’ companies can be very challenging – especially when looking to utilise a distributed network of stores and distribution centres as order fulfilment/pick up/product return sites. As detailed earlier, customer expectations of product availability are markedly different when ordering online than when visiting a physical store – unexpected out of stocks and the inability to successfully complete an online order can have disastrous consequences for customer satisfaction and loyalty.

What numerous companies taking part in this study had found was that the utilisation of RFID to significantly increase the accuracy and transparency of their stock inventory was a critical cog in making their online retailing proposition viable. While in the past, rates of inventory accuracy at 60-65% might be acceptable and manageable in a physical store, such stock discrepancies make omni channel retailing a veritable liability, especially when a customer may be making a special trip to a store to pick up the product they had ordered and paid for online.

Moreover, developing an enterprise-wide system of stock visibility – knowing exactly what stock is in each of the distributed nodes of the business can provide significant competitive advantages in terms of improving the churn and turn of product, reducing overall stock holding levels, minimising discounting practices, and reducing the cost of localised delivery. In many respects, a significant number of the companies investing in RFID were beginning to recognise that the data it generated was increasingly an electronic ‘spine’ that facilitated the various ways in which they delivered omni channel retailing – without it, many of their fulfilment nodes would be too unreliable.

Making the Supply Chain Business Case

Logic suggests that if RFID makes sense and adds significant value when used in retail stores, then surely the same must be the case for its use in retail supply chains. The reality for many of the companies taking part in this research was that the business case for using RFID in the supply chain was and is much harder to make than in retail stores. What many found was that tracking products at item level in distribution centres rarely offers much value added – by their nature they are typically bulk product handling facilities – concerned with shipping tens of thousands of products in large batches rather than single items for sale. As such, levels of inventory accuracy are often higher, making the ROI much harder to make – why invest in large amounts of RFID tag reader technology when existing methods of product identification are already delivering high levels of product visibility and accuracy?

As detailed earlier, there are some retailers that have invested in reading RFID tags in their supply chain – checking inbound and outbound stock movements and see a good return on their investment, but the busines case is more likely to be made when distribution centres are being utilised for E-commerce fulfilment as well as store replenishment. In this scenario, item level visibility once again becomes an issue that can be better managed with RFID.

Informing the Management of Loss Prevention

Managing retail losses effectively is routinely hampered by a distinct lack of item-level data – what products have gone missing? Where were they? When did it happen? Who is likely to be responsible? All are questions that most loss prevention managers struggle to answer. While RFID has frequently been touted as an ‘effective’ way to reduce retail losses, understanding exactly how this will occur has been much more challenging to evidence. The problem is essentially twofold.

First, given the primary business case for most companies investing in RFID is improved inventory accuracy, the RFID delivery mechanism of choice has been swing tickets/stickers applied to products at the point of manufacture. While this has proven to be a cost-effective way of applying RFID tags to individual items, the history of product protection tagging suggests that it is a less than desirable way of securing objects of interest to thieves. Certainly, where it is possible to sew in, embed or encase the tag in a theft-resistant outer shell, then this will mitigate this problem, but for most products currently identified with RFID, they are highly vulnerable to the tag being easily removed.

Secondly, exit alarm systems require not only robust information on the status of the product – activate/not activate the alarm, but also the capacity to read tags reliably in a variety of circumstances. In particular, the alarm system needs to know whether products have been paid for or not and if they are packed into a bag with several other products and items, that the system will still read all the tags accurately. In terms of the former, many users of RFID still do not link the system to their POS or may operate offline till systems – the status of any given tag may be ambiguous as it leaves a retail store28. In terms of the latter, the previous ECR Report on RFID found that levels of read accuracy at exits can be relatively low – in the region of 60-70%.

Taken together, for many retail users of RFID, utilising it for primary product protection purposes is not a viable proposition – too easy to defeat and hard to ensure it is alarming appropriately or reliably. However, the current research did find that users of RFID were innovating in their use of information it made available to improve their management of loss prevention. This was evidenced by its use to better identify refund frauds, where the purchase status of items could be checked and verified. In addition, analysis of the data from more routinised and regular stock counting activities facilitated by RFID provided not only potentially more detailed information on the products most vulnerable to loss, but also enabled the evaluation of security interventions to be carried out more quickly. In this respect, the loss prevention value of RFID is delivered by acting more as a facilitator than a primary instigator of crime control activities. Nevertheless, the value that RFID data offers in terms of better managing retail loss prevention would seem clear.

Delivering an Enhanced Consumer Experience

Throughout this report and the previous ECR study in 2018, the impact of RFID on improving the consumer experience was found to be primarily delivered indirectly – such as making inventories more accurate so that fewer customers experience disappointment in not having the opportunity to buy the exact product they wish to purchase. However, two examples of innovation in the use of RFID which arguably impact more directly on the customer experience were also apparent in the current study – one was in the delivery of smart changing rooms and the other was in the provision of self-checkout.

Smart changing rooms have long featured as an RFID deliverable but to date, few retail companies have managed to introduce them at scale. As detailed earlier, the problem is building a viable business case – proving the ROI has not been easy, but it could be that the measure of value should be considered more in terms of customer satisfaction and enhancing their shopping experience than in a direct measure of economic value such as increased sales. Certainly, the retailer described in this report that was rolling them out at scale felt this was the case – the Net Promoter Score (NPS) was their measure of value for this RFID-based innovation. When this was used, the business believed the value of smart changing rooms was considerable.

Creating increasingly ‘friction-less’ retail environments is very much in vogue presently – delivering the ease and convenience of online shopping but in physical retail spaces. A big friction driver is of course the checkout and pay process – it is hard to find any customer that enjoys standing in line while they wait to pay. Self checkout technologies have become part of the friction-reducing retail landscape, offering the shopper a range of ways to scan and pay for the goods they wish purchase more ‘quickly’. But, speed of checkout can be an illusion – shoppers are typically much more inefficient scanners of products than trained retail staff. However, the act of ‘doing’ can create a perception of increased speed – shoppers think the process is quicker because they are actively engaged in doing something.

What slows down many self-scan transactions is the inability of the consumer to quickly locate the barcodes to be scanned, often adding considerable ‘barcode location time’ to the overall transaction. In addition, self checkout users can be highly unreliable and indeed devious in their use of these systems – not scanning all their items and misrepresenting more expensive goods as cheaper variants. This can generate a significant amount of additional retail losses.

However, one of the retailers taking part in this study had introduced a major innovation to address many of these issues – self-checkout using RFID. Because the tags are recognised without the need for line of sight, product recognition is automated for the consumer – goods that are placed in the checkout zone are registered without the need for the consumer to locate and scan a barcode. In addition, errant user behaviour is much less likely to occur – deliberate non-scanning and mis-representation of products is far harder to achieve in this type of checkout environment.

This is a significant innovation with undoubtedly many benefits for both the consumer and the retailer, but it is far from an easy or cheap example of an RFID-based innovation, hence why only one example was found in a large format retail chain. To operationalise such a programme requires a profound level of organizational commitment to utilising RFID, not least it requires a strategy of 100% of all current and future products to be RFID tagged and for all those tags to deliver a high degree of read reliability. Failure of a tag to scan at a checkout potentially generates an immediate and significant loss – the responsibility for ensuring the registration of all products to be purchased in this scenario has moved away from the consumer and back to the retailer, with the latter now taking responsibility for any failures29.

Given the complexities of delivering RFID-driven self-checkout at scale, it is not surprising that few retailers of any size have adopted this approach thus far. But, it is a good example of perhaps one of the most cutting edge innovations in the retail RFID space to date.

Stages of RFID Maturity

Across the two recent reports undertaken by ECR on the topic of RFID, the way in which the technology has been deployed and used has differed considerably across a range of retailers. Indeed, it is possible to begin to develop a model that captures the various stages of maturity in the way in which RFID is being used in the retail sector. Detailed in Figure 5 are four stages of maturity – Basic, Developing, Established and Leading Edge. These stages are characterised by a number of different RFID indicators: Data Collection (the general location of where RFID tags are typically read); SKU Coverage (the proportion of products that have an RFID tag attached); Tag Reading Capability (how and where tags data is collected); Tag Type (how the tag is applied to products); Tag Application (where the tag is attached to the product); and Data Utilisation (to what purposes is RFID-based data put to use). It is likely that some retailers may well crossover between modes of maturity across some of these key indicators, but overall, it is hoped that the model provides a useful overview of the various stages this research has found in the use of the technology. It should be noted that the examples used to illustrate the types of key indicators found at the various stages of maturity are gleaned not only from the current research, but also from the 2018 study, the online survey and from discussions with industry commentators. In no way is this meant be an exhaustive list but more illustrative of the way in which levels of maturity can be described.

Basic and Developing Utilisation: By far and away most of the companies participating in this research can be located between these two categories – the Plateau of Productivity can be found in the utilisation of RFID in physical stores for the main purpose of improving inventory accuracy and increasingly delivering omni channel retailing. Tagging is mainly done at the point of manufacture, applied to products via stickers and swing tickets and read primarily using handheld readers.

Established Utilisation: Far fewer retailers have reached this level of maturity thus far, where use of the technology can be found both in retail stores and the supply chain. A significant proportion of SKUs are tagged (95%) and may in the right circumstances be sewn into the product as part of the manufacturing process. Tags can be read at various stages in the supply chain including at the Point of Sale and various points in the supply chain. RFID data is used for an expansive range of use cases, including forecasting, audit purposes, identifying refund frauds and facilitating a range of E-commerce processes.

Leading Edge Utilisation: Few retailers have reached this stage where 100% of all products are reliably tagged and can be read through a range of automated readers, including overhead readers, robots, and drones. The tag is firmly embedded in products at the point of manufacture or in the raw materials prior to manufacture. Tags are used to enable self-checkout, manage all forms of product returns, product provenance checking and can be used by manufacturers, retailers, and the consumer.

Figure 5 Use of RFID in Retailing Maturity Model

The Future of RFID in Retailing