A Proven Approach to Shrinkage Reduction

How adopting a systemic, systematic and collaborative approach has been proven to sell more and lose less

Table of Contents:

- Abstract

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Managing Shrinkage: A Missed Opportunity

- - Defining Shrinkage

- - Counting the Cost of Shrinkage

- - The Shrinkage Iceberg

- - Causes of Shrinkage

- - Lack of Co-operation

- - Problems of Managing Shrinkage

- Integrating Shrinkage into Corporate Policy

- - Traditional approaches to shrinkage management are crisis driven

- - Defining Accountability for Shrinkage Reduction

- - Responsibility for Shrinkage

- - Contextualise Shrinkage Against Corporate Objectives

- - Developing Detailed Measures of Shrinkage

- - Implementing Best Practice

- The Shrinkage Reduction Road Map

- - Step 1: Develop a Project Plan

- - Step 2: Map Key Processes & Gather Measures

- - Step 3: Analyse Risk and Identify Root Causes

- - Step 4: Develop Solutions and Prioritise Actions

- - Step 5: Implement and Trial Solutions

- - Step 6: Evaluate Implementation

- - Road Map Epilogue

- - Sonae and Colgate Palmolive

- - Sainsbury’s and a Consortium of Branded Spirits Suppliers

- - Tesco and Gillette

- - Wickes, Lloyd Fraser and GET

- - Coop Italia and Procter & Gamble

Languages :

This report, first published in 2001, with an updated version released in 2003, sets the stage for the ECR Retail Loss Group’s overarching philosophy of ‘sell more and lose less. It is based upon extensive research with a range of European retailers, including a series of case studies charting how businesses went about adopting this approach to better manage their retail losses.

The original printed version of this report includes a CD Rom containing the overall rationale for the ‘ECR’ approach together with a series of tools and techniques that retailers could utilise.

The report notes that average European retailer profits could be 29 per cent higher if they could reduce their losses through shrinkage by one half. In addition, it highlights some of the consequences of shrinkage, such as out of stocks and restricted product availability, which impact directly upon shopper satisfaction.

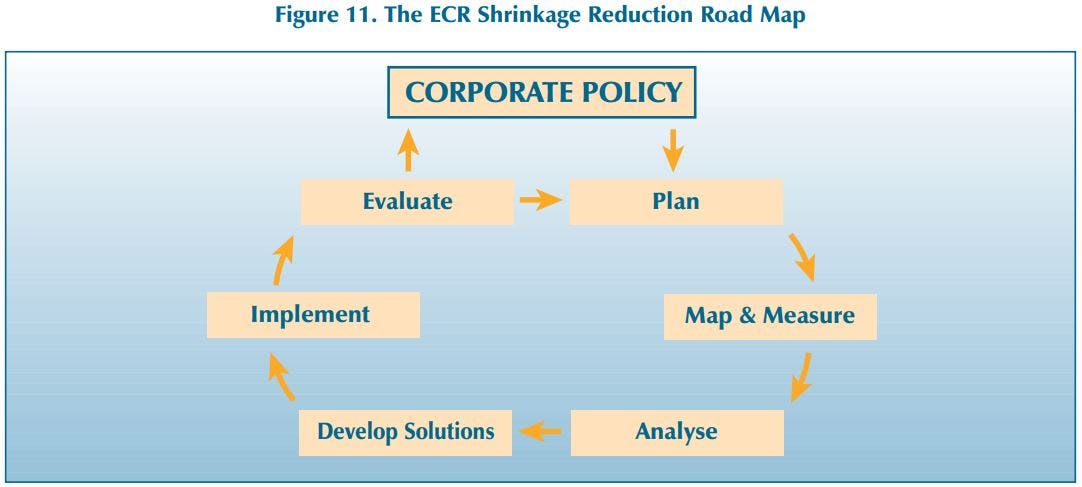

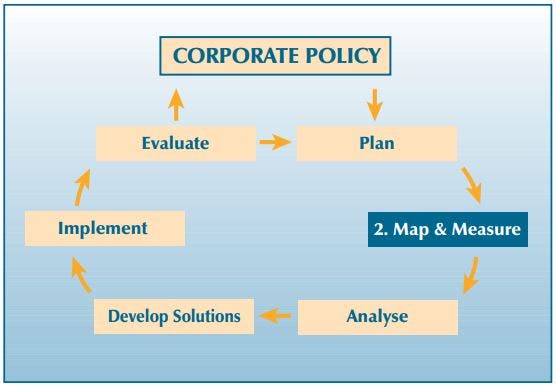

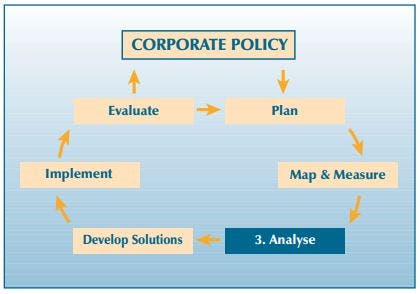

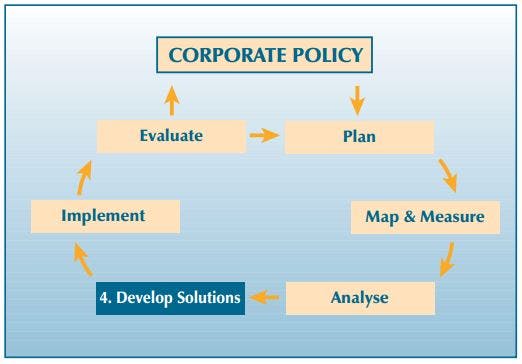

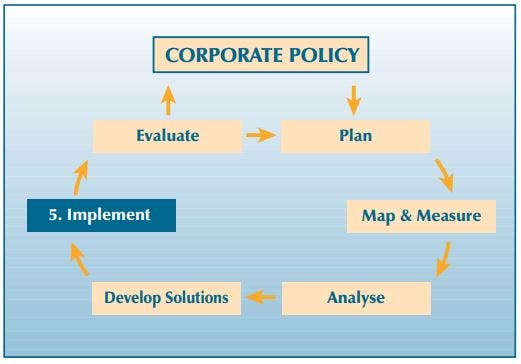

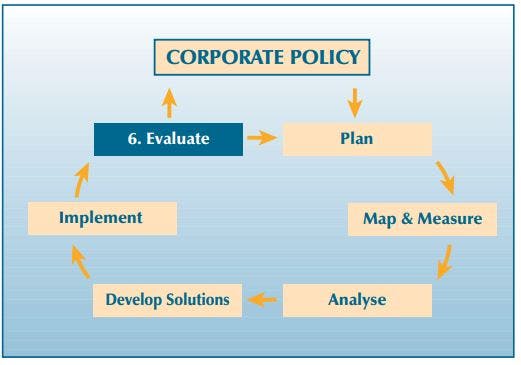

A central component of the report is the Shrinkage Reduction Road Map – an approach that is considered to be both systemic and systematic and designed to deliver real benefits to the companies using it. The Road Map is made up of six steps: 1) Develop a Project Plan; 2) Map Key Processes and Gather Measures; 3) Analyse Risk and Identify Root Causes; 4) Develop Solutions and Prioritise Actions; 5) Implement and Trial Solutions; and 6) Evaluate Implementation.

The Report stresses that it is important to recognise that the Road Map needs to be incorporated into a shrinkage reduction strategy that is itself fully integrated into the overall corporate policy of the company. Companies need to appreciate that unless and until companies give shrinkage management the same weight and importance as other functions within the business such as sales, distribution and marketing, they will continue to suffer unacceptably high levels of loss.

This seminal study goes on to argue that an integrated shrinkage policy that is committed to ongoing improvement, recognises the value of working with partners throughout the supply chain, and uses the ECR Road Map to deliver targeted solutions to particular problems, will make a significant contribution to the overall profitability of the business.

It concludes by suggesting that the application of this approach to managing shrinkage can bring companies a real opportunity to increase profits and increased customer satisfaction – a win-win outcome the FMCG sector.

Abstract

This report, first published in 2001, with an updated version released in 2003, sets the stage for the ECR Retail Loss Group’s overarching philosophy of ‘sell more and lose less. It is based upon extensive research with a range of European retailers, including a series of case studies charting how businesses went about adopting this approach to better manage their retail losses.

The original printed version of this report includes a CD Rom containing the overall rationale for the ‘ECR’ approach together with a series of tools and techniques that retailers could utilise.

The report notes that average European retailer profits could be 29 per cent higher if they could reduce their losses through shrinkage by one half. In addition, it highlights some of the consequences of shrinkage, such as out of stocks and restricted product availability, which impact directly upon shopper satisfaction.

A central component of the report is the Shrinkage Reduction Road Map – an approach that is considered to be both systemic and systematic and designed to deliver real benefits to the companies using it. The Road Map is made up of six steps: 1) Develop a Project Plan; 2) Map Key Processes and Gather Measures; 3) Analyse Risk and Identify Root Causes; 4) Develop Solutions and Prioritise Actions; 5) Implement and Trial Solutions; and 6) Evaluate Implementation.

The Report stresses that it is important to recognise that the Road Map needs to be incorporated into a shrinkage reduction strategy that is itself fully integrated into the overall corporate policy of the company. Companies need to appreciate that unless and until companies give shrinkage management the same weight and importance as other functions within the business such as sales, distribution and marketing, they will continue to suffer unacceptably high levels of loss.

This seminal study goes on to argue that an integrated shrinkage policy that is committed to ongoing improvement, recognises the value of working with partners throughout the supply chain, and uses the ECR Road Map to deliver targeted solutions to particular problems, will make a significant contribution to the overall profitability of the business.

It concludes by suggesting that the application of this approach to managing shrinkage can bring companies a real opportunity to increase profits and increased customer satisfaction – a win-win outcome the FMCG sector.

Executive Summary

There is an increasing recognition of the scale and extent of the problem of shrinkage in the FMCG sector. Current estimates suggest that in Europe alone it accounts for €18 billion a year. There is also a growing realisation that existing approaches to tackle this problem have been piecemeal, partial and largely ineffective. As we outline in this book, on average European retailer profits could be 29 per cent higher if they could reduce their losses through shrinkage by one half. In addition, some of the consequences of shrinkage, such as out of stocks and restricted product availability, impact directly upon shopper satisfaction.

Over the past three years the ECR Europe Shrinkage Group has developed a new approach to tackling the problem of stock loss, based upon genuine inter-company collaboration throughout the supply chain. The outcome of this work has been the development of the Shrinkage Reduction Road Map – an approach that is both systemic and systematic and designed to deliver real benefits to the companies using it.

It is important to recognise, however, that the Road Map needs to be incorporated into a shrinkage reduction strategy that is itself fully integrated into the overall corporate policy of the company. Companies therefore must appreciate that unless and until they give shrinkage management the same weight and importance as other functions within the business such as sales, distribution and marketing, they will continue to suffer unacceptably high levels of loss.

An integrated shrinkage policy that is committed to ongoing improvement, recognises the value of working with partners throughout the supply chain, and uses the ECR Road Map to deliver targeted solutions to particular problems, will make a significant contribution to the overall profitability of the business.

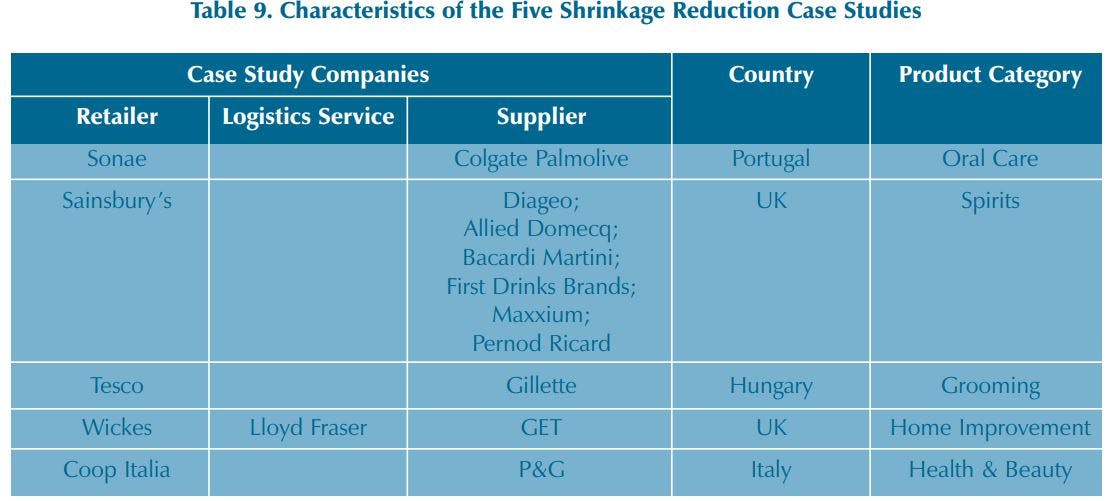

The case studies presented in this Blue Book offer real examples of how the Road Map can be used to develop and deploy end to end solutions – it has been tried and tested to show it is practical, easy to use, robust and capable of delivering results in just a few weeks. Detailed in this book and the accompanying CD is the rationale for adopting this approach and the tools and techniques that can be used to implement the Road Map

Above all, the application of this approach to managing shrinkage can bring companies a real opportunity to increase profits and customer satisfaction – a win-win outcome that should make this Blue Book essential reading for the FMCG sector!

Introduction

The aim of the ECR Europe shrinkage project was to identify the scale and extent of stock loss in the Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) sector, and develop a joint vision on how retailers, manufacturers and distributors could work together to reduce the problem of shrinkage.

In recognition of the complex nature of the stock loss problem, two academic organisations were selected to manage the research programme. The University of Leicester was chosen for their expertise in the area of security and retail crime while the Cranfield School of Management was chosen for their specialism in the field of supply chain management and logistics. Working together these two groups of experts have combined their knowledge to bring fresh thinking to the FMCG sector in an effort to achieve a coherent and comprehensive approach to tackling stock loss. This study breaks much new ground with the first pan-European study of stock loss in the FMCG supply chain and the development and validation of the Road Map – a collaborative and systematic approach to reducing stock loss.

This report is intended to be a concise document, focused on convincing the industry to adopt the Road Map. It draws on an earlier report by the University of Leicester dealing with the size and nature of the stock loss problem within the FMCG sector, based upon a pan-European survey of retailers and manufacturers1 , and research carried out by Cranfield School of Management on the supply chains of 23 European companies.

If collaborative efforts are increased, the industry could start to reduce its losses significantly

Looking forward there is good reason to believe that collaborative efforts, guided by the Road Map, can contribute to total systems efficiency throughout the supply chain. While the evidence shows that there are opportunities for increased internal collaboration in all areas of the supply chain, it is the collaborative efforts between retailers, distributors and manufacturers working to reduce stock loss within retail stores where the most impact is likely to be made. Companies along the supply chain need to work together to identify improvements in a wide range of areas including: product design, packaging, administration, logistics, stock control, replenishment planning, stock room management, store layout, shelf design and people management. Getting it right requires teamwork, a structured approach and hard data on the extent and nature of stock loss throughout the entire supply chain: a paradigm shift away from where many companies are today. But if this is done, all parties, not least the shopper, who will see greater availability and choice on the shelf, will benefit. This in turn will increase sales and profits for both retailers and manufacturers.

Getting it right will require teamwork, a structured approach and hard data on the extent and nature of stock loss throughout the entire supply chain

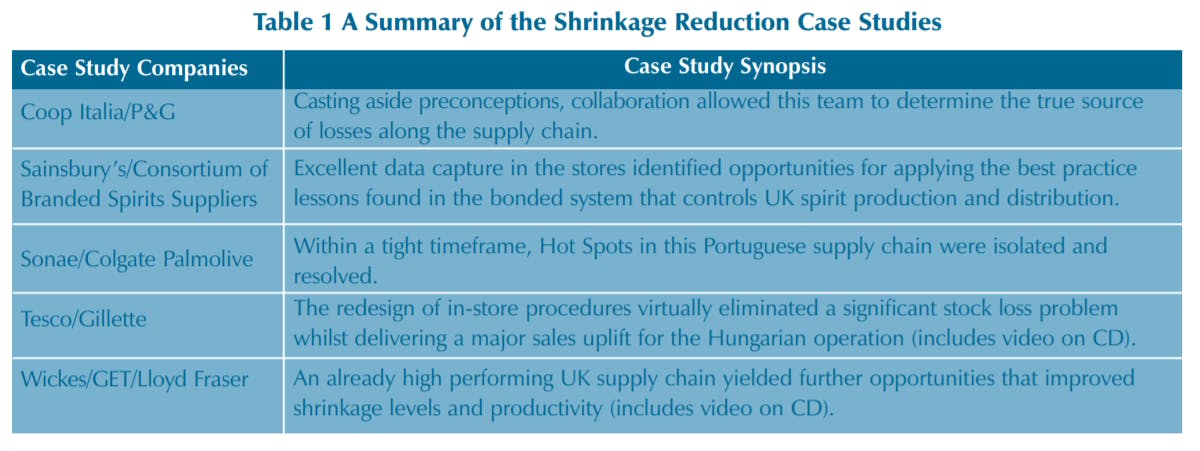

A CD-ROM accompanies this ECR Blue Book. This contains material that provides practical assistance for teams undertaking a loss reduction project. This includes tools and techniques that help the team follow the steps in the Road Map and come in various forms, including questionnaires, checksheets and spreadsheets. The CD also includes a series of case studies taken from projects carried out by companies in the ECR movement, consisting of a presentation from the project teams. It also includes two videos. A brief synopsis of each case is presented in Table 1 overleaf.

Managing Shrinkage: A Missed Opportunity

Defining Shrinkage

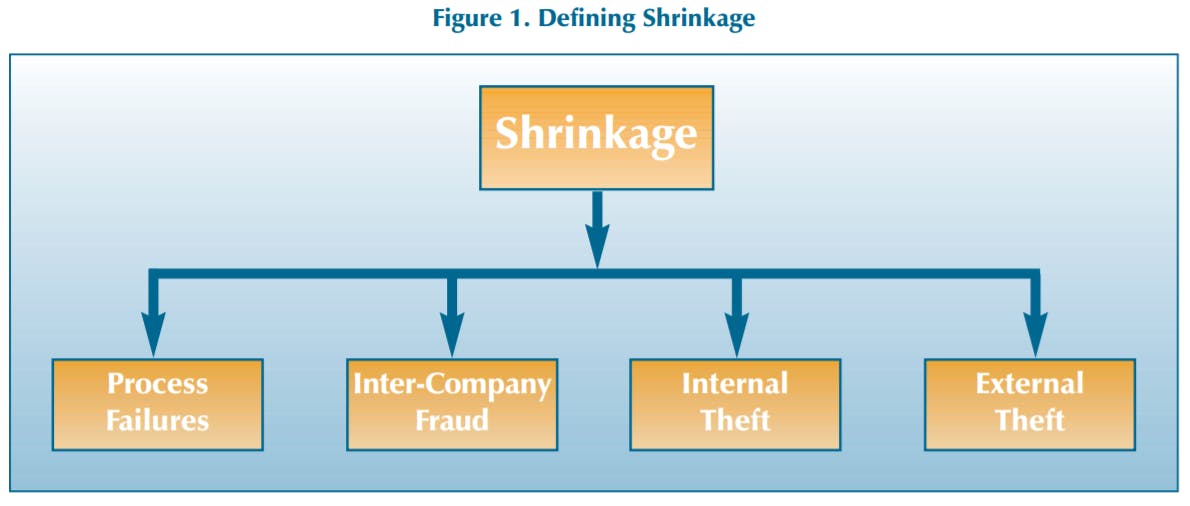

In order to resolve shrinkage, it is important to have clarity about what it is. The ECR team considers shrinkage as consisting of four elements, as shown below.

Process failures can occur in the physical flow of goods along the supply chain, in information systems or in finance systems. The effect of failure in any one of these systems is that stock will be lost and/or payment for goods is incorrect. When considering fresh product, process failure is likely to be the biggest cause of shrinkage. Inter-company fraud leads to shrinkage when trading partners intentionally deliver the wrong quantities and/or charge for goods to their advantage. This tends to occur when poor processes, procedures or controls are exploited. Whilst the effect is similar, theft is categorised as being either internal, e.g. by employees or contracted staff, or external, e.g. shop thieves or burglars. The ways theft occurs can vary significantly although in many instances it is a consequence of poor processes, procedures or controls within a company. Theft accounts for a significant proportion of shrinkage in the FMCG sector with ‘Hot Products’2 being particularly vulnerable.

Counting the Cost of Shrinkage

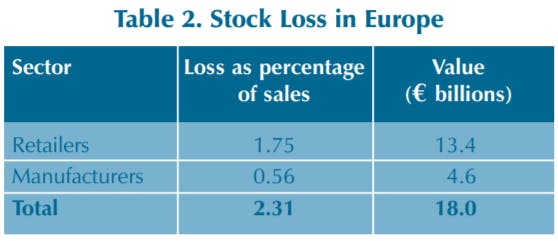

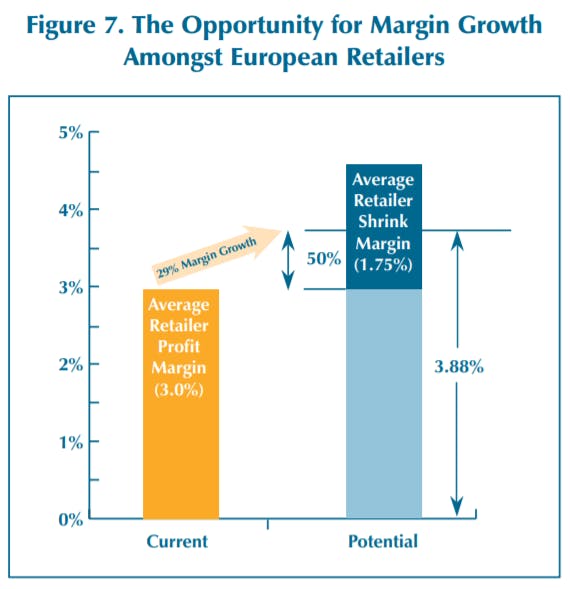

The FMCG sector in Europe is big business with a combined market turnover of over €820 billion. The groundbreaking research carried out on behalf of ECR Europe showed that shrinkage is a major threat to the efficiency and effectiveness of the sector. In 2000, retailers lost €13.4 billion due to shrinkage, equating to 1.75% of turnover or €258 million a week. Manufacturers are not immune from this problem and lost €4.6 billion, accounting for 0.56% of turnover or €89 million a week. Taken together, the FMCG sector is haemorrhaging €18 billion a year due to stock loss. In addition, retailers alone are spending €2.14 billion trying to tackle this problem. The impact on profitability is dramatic and retail profits could be 29% higher if companies reduced losses due to shrinkage by 50%.3

The FMCG sector is losing €50 million a day due to shrinkage. Annually this is equivalent to the GDP of Luxembourg

The FMCG sector is highly complex with many manufacturers having logistical webs covering all of Europe, while many retailers have product ranges between 40,000-250,000 SKUs. Research shows that all points of the logistical chain are vulnerable to loss not just the retail store. In 2000, €6.1 billion of stock was lost even before it made it to stores.

The Shrinkage Iceberg

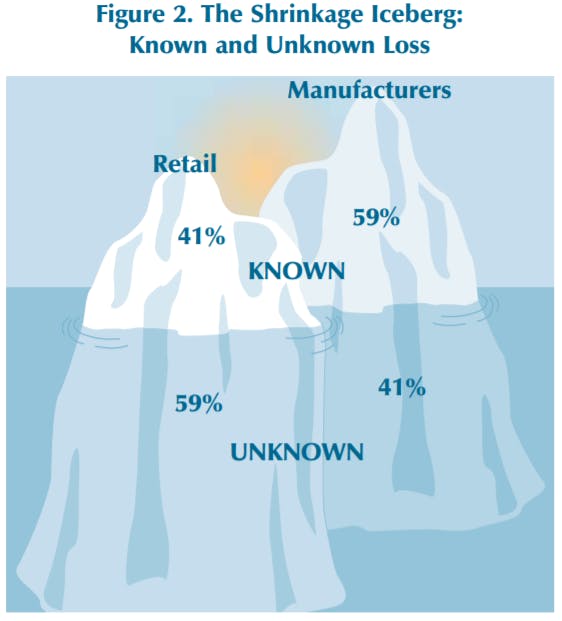

Information on stock loss is shrouded in ignorance and hearsay. At best, company information on this problem is partial and incomplete and at worst non-existent. Research carried out for ECR Europe found that most retail companies do not know where, how or when the majority of their losses occurred. Manufacturers can only boast a slightly better record although even they cannot account for over 40% of their losses. In 2000, retailers were unable to explain how €7.9 billion of stock was lost, while manufacturers were unable to pinpoint how €1.9 billion of their products ‘disappeared’. Taken together, the FMCG sector cannot account for nearly €10 billion of stock.

Gathering high quality data that is reliable, timely and complete needs to be a priority for any future stock loss reduction strategy. At the moment, while a number of companies regularly collect computerised information on process failures, very few keep track of all the shrinkage threats, in particular theft. If a problem is not recorded and analysed, it is highly unlikely that it will be understood or tackled effectively. Retailers and manufacturers do not know where, how or when they lose €192 million a week.

Without doubt, a paucity of data plays a pivotal part in producing poor product protection

Causes of Shrinkage

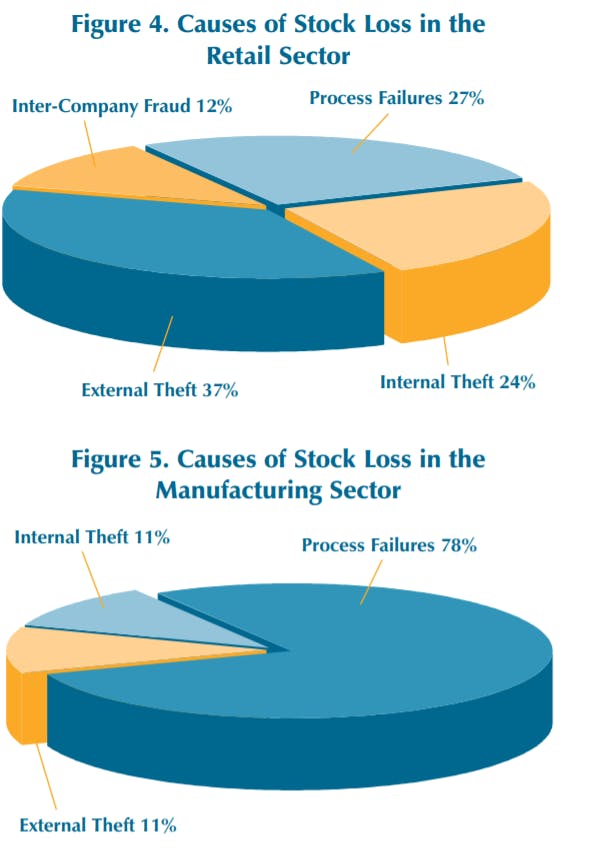

Highlighting how stock is lost is a vital part of any effective stock loss reduction strategy – it can identify priorities and enable responses to be tailored to specific needs. The research showed that for retailers, the biggest perceived threat came from theft – over €8 billion or over 60% of all stock loss was thought to be due to staff and ‘customers’ thieving from their organisations. Process failures were seen as the next major cause of shrinkage – €3.6 billion lost due to products being ‘misplaced’ in the supply chain, getting damaged or going out of date. For manufacturers, the biggest culprit was process failures with over three-quarters of all losses being seen as a consequence of this. For them theft was less of an issue although it still accounted for over €1 billion of loss in 2000. Theft is thought to account for over €9 billion of loss in the FMCG sector

Lack of Co-operation

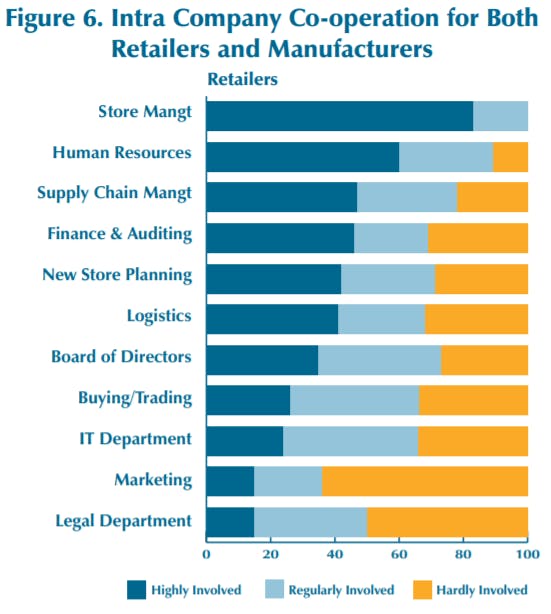

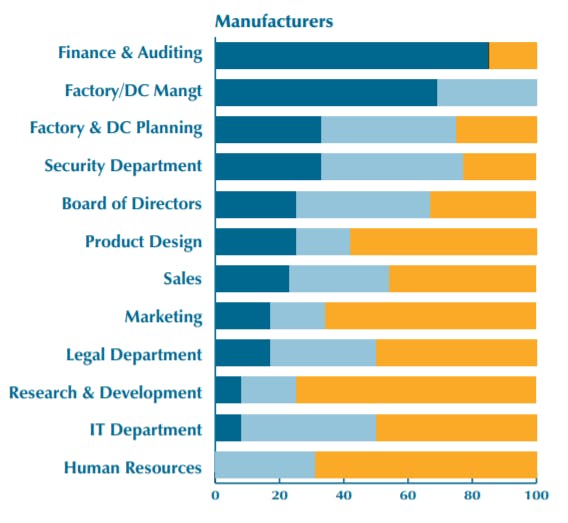

Shrinkage is a problem that transcends departmental and company boundaries – it is a common problem requiring shared solutions. The ECR Europe research showed a lack of cooperation not only within companies, but also between companies who are involved in the supply chain. For the most part retailers see stock loss as the exclusive responsibility of the security/loss prevention and audit departments, and store management, while manufacturers tend to put the onus upon the logistics team to deal with this problem. Few other departments are highly involved, with retailers rarely involving buyers, marketing, the IT department or indeed the Board of Directors. Similarly, manufacturers rarely make use of the research and development team, sales and marketing or human resources.

The picture is even gloomier when inter-company co-operation is considered. For retailers, the current climate is characterised by an emphasis on reactive collaboration with security providers and the police. Relatively few pointed to work with individual manufacturers or their representative organisations. Manufacturers were even more isolated with less than 1 in 3 working with individual retailers on issues of stock loss and most focusing their co-operative efforts on third party logistics service providers.

Problems of Managing Shrinkage

The management of shrinkage has suffered from a number of inter-related problems that have combined to limit its effectiveness in dealing with an issue that is costing businesses billions of Euro a year both in terms of losses and expenditure on so called ‘solutions’.

Unfortunately Necessary

Shrinkage management suffers from an image problem within organisations. Too often it is not seen as actively contributing to bottom line profitability. It is seen as a regrettable consequence of doing business or a function that can be called upon when things have gone badly wrong, such as a break-in, when products have been contaminated or a member of staff has been attacked. To this end, it is often seen as the task that requires skills similar to those used in public policing, i.e. detaining offenders and employing guards.

Juggling Priorities

The roles and responsibilities of security/loss prevention departments are often many and varied, ranging from issues of health and safety, through monitoring contract guarding companies, to responding to kidnap attempts on senior members of the organisation. Some of this myriad of duties are statutory requirements. Non-compliance can result in substantial penalties, which means that stock loss receives a lower priority from those people tasked with its management.

Solutions Searching for a Problem

Many of the methods and approaches currently adopted by shrinkage managers focus on one particular problem: shoplifting, coupled with an almost obsessive belief that the answer can be found in a quick fix technological panacea. As the data presented above has shown, retail shrinkage managers themselves suggest that only about onethird of loss is caused by external theft, and yet as one senior manager put it: ‘tackling shoplifting accounts for about 95 per cent of our security budget’. In addition, security services and technology providers have been able to drive the stock loss agenda on a ‘we have a solution, can we now find a problem’ basis.

‘Tackling shoplifting accounts for about 95 per cent of our security budget’ (Senior Retail Manager)

Myopic Management

Many shrinkage practitioners have a tendency to see the problem as only occurring at the end of the supply chain – after the products eventually reach the store. This is in part a function of the prioritisation of shoplifting as the primary cause of stock loss. The store is the point at which customers interact with the products and where many of the current technology ‘solutions’ are most easily applied. But as shown above, up to one third of loss takes place before the goods have reached the retail outlet, highlighting the need to look at losses of goods in transit and while being stored in distribution centres. Certainly the stores are a very vulnerable part of the supply chain, but they are only a part of the chain and stock loss practitioners need to look beyond the retail outlet and recognise that good loss prevention is about securing the entire supply chain.

Time to Take Action

The research carried out for ECR Europe clearly shows that to date the FMCG sector has neglected the problem of shrinkage and its effective management. It is a sector suffering enormous losses, lacking any detailed understanding of the extent and nature of the problem, with existing approaches tending to be ad hoc, piecemeal, partial and lacking in intra- and inter- company cooperation. It is time for the FMCG sector to act and tackle this problem through a systematic and coordinated approach. The consequence of not doing this is an ever-increasing bill for shrinkage, which currently stands at €18 billion per year.

Integrating Shrinkage into Corporate Policy

Recent research carried out by ECR Europe examined the causes of shrinkage, looking at 12 FMCG supply chains. Each supply chain was investigated from supplier right through to the shelf in the retailers’ store. A key phenomenon observed in the approaches adopted to tackle shrinkage was that they tended to be crisis driven – resource and attention was only applied when a significant event had occurred or extraordinary levels of loss had come to light. The response was ad-hoc and usually driven by a series of well-worn anecdotes – ‘shoplifters must be the problem’.

This research also showed that while a multitude of alternative solutions to shrinkage exist, loss prevention specialists often prioritised those that involved the use of technology. In addition, it was found that efforts to reduce shrinkage typically failed to consider the impact they have on other business objectives, for instance sales, stock availability and customer satisfaction. Solutions were often imposed unilaterally by one party in the supply chain without considering the impact on other groups; something which is clearly at odds with the collaborative approach supported by ECR.

Finally the implementation of solutions was not followed by an analysis of their effectiveness – there was little evidence of the collection of hard data on what impact the intervention had had within the supply chain. In stark contrast to good practices observed elsewhere in the FMCG industry, shrinkage reduction cannot claim to be part of the ‘knowledge economy.’ The lack of data on the impact of previous shrinkage solutions therefore undermines the ability of businesses to make sound business decisions. When the next crisis occurs the old cycle continues: ad-hoc reactions based on anecdotes emphasising the problem of shoplifting and the usefulness of technology-based solutions.

Traditional approaches to shrinkage management are crisis driven

In order to break out of this cycle, the management of shrinkage needs to be fully integrated into overall corporate policy, giving it the same weight and importance as other functions within the business such as sales, distribution and marketing. In addition, it needs to develop a corporate shrinkage policy that extends beyond the company to effectively incorporate all supply chain partners. An integrated shrinkage policy needs to be properly resourced, it needs appropriate channels of accountability and it needs to incorporate the mechanisms to capture high quality shrinkage data so that key performance indicators can be developed and the value of solutions assessed.

Through adopting such an approach, companies are far more likely to develop and deploy best practice in reducing shrinkage throughout the supply chain. This Blue Book is designed to help with this process. The ECR Shrinkage Reduction Road Map described in detail later in this book is a tried and tested tool to help companies to develop a corporate shrinkage strategy committed to ongoing improvement and recognised as contributing to the overall profitability of the business. The key components of developing an integrated shrinkage policy are outlined below.

Defining Accountability for Shrinkage Reduction

To deliver the opportunity that shrinkage reduction presents for profit enhancement, there needs to be a senior manager or ‘champion’ accountable for it. This person co-ordinates the development of the shrinkage policy, ensuring that the knowledge and experience of stakeholders from across the supply chain are incorporated. They then oversee its management within their company and ensure collaboration with supply chain partners. More specifically, this person ensures the following actions are undertaken:

- Set and agree policy:

– Internally with the senior management team.

– Externally in collaboration with supply chain partners.

- Set KPIs:

– Identify the metrics needed to make informed decisions on shrinkage issues.

– Design a system to collect and collate the necessary information.

- Allocate responsibility to deliver the policy:

– Collect data.

– Research/mine data.

– Plan and undertake actions to reduce loss.

- Monitor performance and adherence to the policy and revise as appropriate.

These activities require resources and naturally no management team should make such a commitment lightly. However the ECR research found that companies employing dedicated security/loss prevention departments and audit departments suffered much lower losses due to shrinkage. For those retailers with a security/loss prevention department, the level of stock loss was 27% lower. Similarly, manufacturers with such a specialist department also benefited from significantly lower levels of loss. The impact of dedicated audit departments was even more dramatic – retailers with such a function had losses 39% lower than those companies without such a department. Once again, this picture was mirrored in the data from manufacturers. It was also found that having the opportunity to report directly to the Board of Directors significantly improved the performance of these specialist teams. The conclusion is that having specialist teams that report directly to the Board of Directors can significantly reduce losses from shrinkage.

Responsibility for Shrinkage

Whilst it is necessary to assign accountability for delivering results at a senior level in the organisation, responsibility for undertaking the tasks necessary to reduce losses should be devolved to operational managers throughout the organisation. Stock loss is a cross-functional problem and examples of poor management that lead to stock loss can be seen in most areas. For example:

- Logistics managers failing to follow receiving and dispatch procedures.

- Operations managers storing vulnerable products in locations that are difficult to supervise.

- HR managers failing to carry out routine checks on new employees.

- Facilities managers failing to liase with architects to design out well-known problems in store layout and warehouse design.

- Product designers failing to ensure packaging protects its contents.

- Category mangers failing to set up product attributes correctly.

- Sales managers overstocking shelves and promoting vulnerable products without considering the impact on losses.

It is therefore necessary for managers in these and all other functions to be aware of their responsibility to reduce shrinkage. Their roles should therefore include an obligation to collate and act upon data on stock loss within their sphere of influence. Results from action to resolve outstanding issues are then reported up the management structure to the person accountable for shrinkage.

Contextualise Shrinkage Against Corporate Objectives

Successful shrinkage management requires it to be recognised and prioritised as a key component within the objectives of the corporation. To be effective, shrinkage results should be communicated regularly at board level, not hidden from view amongst the general cost of doing business. Shrinkage justifies this need for managerial attention because of two factors:

- Impact of shrinkage on corporate results.

- Impact of shrinkage on shopper satisfaction.

Impact of Shrinkage on Corporate Results

Shrinkage thwarts the efforts of retailers and manufacturers to deliver their financial objectives as the cost of shrinkage is both significant and has a negative impact upon sales. Considering the cost of shrinkage, the most significant element is typically the cost of lost stock. Described in detail earlier, it is worth recapping that the FMCG sector is losing 2.31% of the value of its turnover to shrinkage. The significance cost of shrinkage becomes clearer when considered in terms of retailer profitability. A review of 25 European supermarket chains’ annual reports for year 2000 revealed an average profit margin of 3%, while the cost of shrinkage was calculated at 1.75% of turnover. If the cost of shrinkage was halved, the retail sector could increase its average profitability from 3% to 3.88%, a growth of nearly one-third (Figure 7).

In addition to this figure is the cost of responding to shrinkage through a variety of loss reduction measures, including the installation of equipment, employing security personnel, adding checks to procedures, and the cost of managerial effort required to implement and supervise these measures. The ECR survey estimated that this costs FMCG European retailers and manufacturers approximately €2.1 billion a year.

Impact of Shrinkage on Shopper Satisfaction

Shrinkage can negatively impact upon customer satisfaction in two key ways: by causing out-ofstocks (OOS) at retail outlets; and restricting access to goods that retailers perceive to be at high risk from shrinkage.

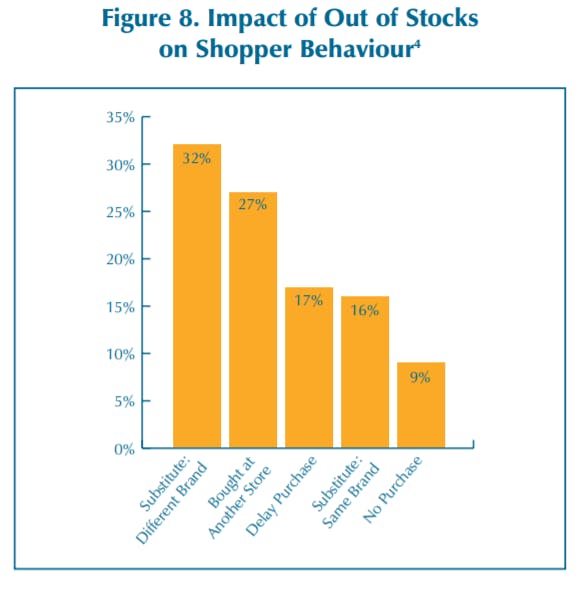

Automatic stock management systems use sales data to determine when to replenish a store. Shrinkage can cause shelves to become empty before the reordering point is reached. Without any stock on the shelf, no sales are made and so the reordering point is not reached. This causes the shelves to remain empty until the time either a manual order is generated or the inventory record is corrected. Shopper inconvenience and inconsistent on-shelf-availability negatively impacts upon the relationship between consumers, their preferred products and their preferred retail outlets. Even occasional gaps in availability can diminish loyalty, which may increase shoppers’ propensity to permanently switch product or store (see Figure 8).

Shrinkage also has an impact on shopper satisfaction by restricting product choice and convenience. The range of products carried by a retailer may be restricted where they perceive that the threat of shrinkage is too high. For example shoppers may want to buy DVDs along with their regular shopping but the threat of losses in this category may cause a grocery retailer not to stock them. Similarly, a retailer may feel that the sale of certain fresh products are too unpredictable, leading to product going out of date, and so they decide to limit their range. In addition, retailers may take items from open sale if they perceive the threat of shrinkage to be too high. This often involves relocating the product away from the usual aisle and locking them away. Shoppers often interpret an empty shelf as meaning the store is out of stock, whether there is a sign explaining the situation or not, so they behave accordingly. Where they recognise that they must look elsewhere for the product, the shopper may have to find a member of staff to serve them. This goes against the common practice of self-service retailing and is not to the liking of many shoppers. This can lead to them displacing their purchase to another product or another store or going without. It is unlikely that any of these conclusions increases shopper satisfaction.

Shrinkage impacts on shopper satisfaction by restricting product choice and convenience

Developing Detailed Measures of Shrinkage

Resolving shrinkage would be a simple matter were it possible to identify incidents at the time they occur and a person was accountable for responding to it and resolving the problem. The lesson that can be drawn from this cosy scenario is that before it is possible to act to resolve shrinkage it is necessary to determine what and how many items are being lost, where the losses are occurring and when.

Defining Shrinkage

Opinions vary on a definition for shrinkage. Some take a very narrow perspective and limit it to the loss of stock only, choosing to exclude the loss of cash from an organisation, or consider it to relate only to the losses that cannot be explained – ‘unknown losses’ as they are usually referred to. At the other end of the spectrum, some argue for a much more inclusive, broad ranging definition which encompasses both stock and cash, as well as the losses that result from shrinkage events – ‘indirect losses’ – such as out of stocks caused by shop theft, the sale of stolen goods on the ‘nonretail’ market or the production of counterfeit products. In addition, some feel that the expenditure incurred responding to stock loss should also be included in the overall cost of shrinkage.

As detailed earlier, the ECR Europe Shrinkage Group has developed a definition that has received relatively broad acceptance, which strikes a middle ground between the two, driven in part by the current limitations imposed upon the ability to accurately measure the impact of shrinkage upon organisations. It is based upon four categories of shrinkage encompassing both stock and cash and made up of inter-company fraud, internal theft, external theft and process failures.

Measuring Shrinkage

In order to get rigorous and robust data on the nature and extent of shrinkage within a business, the key questions of Where? What? How much? and When? need to be answered.

Where: Losses are not evenly spread across the supply chain. The location where they occur should be determined by measuring the loss at each separate site, including individual distribution centres and stores. More detailed measures are also needed within sites to determine the exact location of failures in the supply chain. These measures can be gathered by various means including taking random samples, for example the accurateness of a DC picking operation can be determined by assessing the accuracy of picked items on randomly selected pallets.

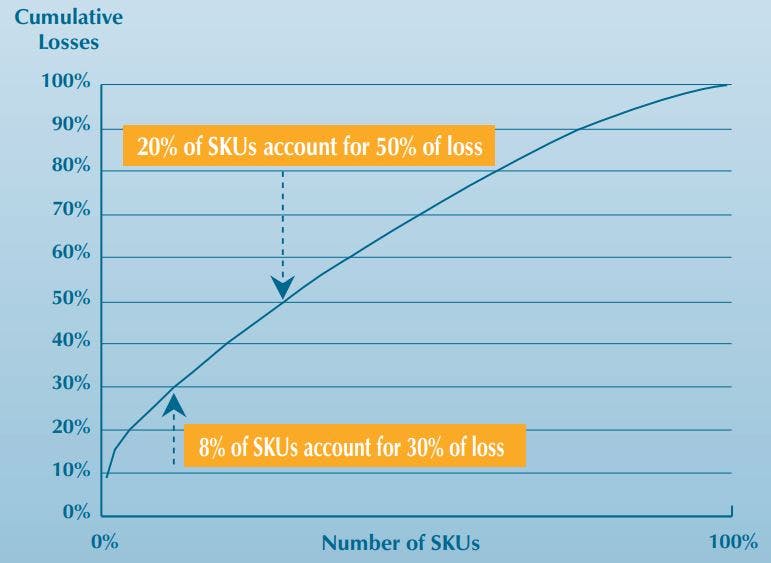

What: Losses are not evenly spread across all products. Even within a particular category or product range the overall loss will be concentrated on certain items. It is therefore necessary to collate data on losses by stock keeping unit (SKU) or reference.

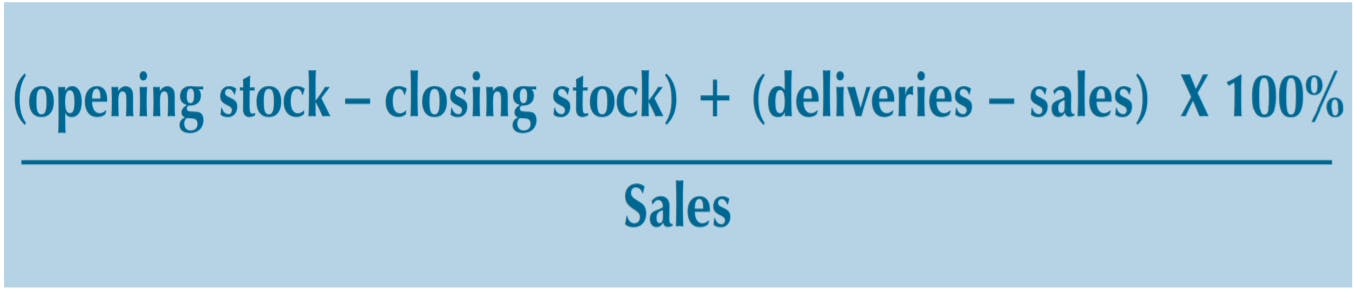

How much: In order to determine the direct cost of shrinkage for a given time period, the value of items and/or cash lost must be captured. This figure is expressed as a percentage of sales value, by using the following formula:

When: The frequency that measures are taken determines the ability to identify when losses occur. By measuring stock levels at the start and again at the end of a time period and then subtracting sales from recorded deliveries provides a measure of stock loss over a given period. The most common measurement interval is annually. This normally coincides with the annual stock-take in a business, which is necessary for accounting purposes. This allows a company to determine it’s annual stock loss. However it is not possible to specify the point in time over that year when losses occurred. Reducing the time period for undertaking this calculation narrows the time-window in which the loss could have occurred and increases the likelihood of understanding who was responsible and where it took place.

In order to understand the nature and extent of shrinkage, the key questions of Where? What? How much? and When? need to be answered

CASE STUDY EXAMPLE 1

In the Sainsbury’s BWS Case Study, data was gathered at the following intervals:

- Diageo’s DC counts inventory in a storage location the day after it had been moved.

- Allied Domecq’s DC ‘blind checks’ the inventory in a pick location every time product is picked from it.

- Sainsbury’s stores count their spirits every morning.

In each of these three operations, information is gathered very frequently. Where losses are found to occur it is therefore possible for the person accountable for stock loss to investigate each incident and act to resolve it.

Methods for Data Analysis

Having gathered the stock loss data it is necessary to determine the causes of losses in order to take action to reduce future problems. Not all causes of stock loss are easy to determine. Many occur intermittently and prove difficult to uncover. Thorough research of the causes of loss often requires the in-depth analysis of a large amount of data. This may need to be collated from a variety of sources and locations over an extended period of time.

The ECR research found that within the FMCG sector, most retailers keep records of inter-company fraud and process failures, but few kept computerised records of internal and external theft, either at a company or store level. Manufacturers were found to keep computerised records of process failures, but few recorded any form of theft on a computerised system. The majority kept either no record whatsoever or only paper files. It is only through the use of computerised databases that trends can be identified and a more informationled strategic approach can be adopted to deal with all the elements that account for shrinkage.

It is clear that the methods used to store and communicate information need to be rigorous, robust and reliable. For example, in order to determine which stores in a retail chain are responsible for a disproportionate amount of loss it is necessary to collect loss metrics in a common way, capture this information electronically and store it centrally.

Implementing Best Practice

At the heart of any corporate policy is the need for a business to make sufficient profit to ensure its survival. Europe’s €18 billion stock loss problem presents a substantial opportunity to achieve this most basic of aims. Adopting available best practice has the potential to make a significant contribution to releasing this opportunity for all the sectors’ stakeholders including shoppers, retailers and manufacturers.

Lessons learnt from the ECR case studies identify the following practices as ones that help organisations deliver improvements and that appear to have universal applicability in a range of different circumstances:

- Take a collaborative approach to reducing shrinkage.

- Focus effort on Hot Products; Hot Stores; and Hot Spots in the supply chain.

- Capture and share best practice.

Take a Collaborative Approach to Reducing Shrinkage

At the core of the ECR movement is the advancement of robust management methods in retailing. In loss prevention this means informationled decision making in collaboration with supply chain partners. Operationalising this approach requires the systematic investigation of the root causes of shrinkage. Undertaking this along the supply chain brings a holistic approach to the problem. A prerequisite for success is to have a commitment to collaboration between manufacturers, logistics service providers and retailers along the supply chain. Therefore companies should seek to drive the delivery of these benefits on two fronts:

- Throughout their organisation.

- Across the supply chain.

Collaboration within a company provides the means to resolve problems beyond the scope of individual functions to solve.

Methods used to store and communicate information need to be rigorous, robust and reliable

Collaboration is therefore necessary between departments, such as operations, buying, logistics, marketing, IT, security and finance.

Likewise, collaboration between companies resolves problems that are beyond the scope of separate companies to solve. Inter-company collaboration within the ECR movement traditionally involves vertical supply chain partners working together, i.e. customers and suppliers. As the ECR shrinkage case studies show collaboration should extend to include logistics service providers as well. Collaboration can also be amongst competing organisations, for example where they work within the remit of a trade body to resolve common issues.

The results of this work will be to:

- Design loss prevention solutions into the fabric of processes and facilities.

- Ensure that these solutions effectively contribute to total supply chain efficiency, instead of solving a problem at only one end of the chain.

- Implement simpler and cheaper controls to minimise loss.

"Reducing stock loss presents a substantial opportunity for performance improvement throughout the supply chain"

Focus Effort on Hot Products, Hot Stores and Hot Spots in the Supply Chain

Manufacturing, distribution sites and retail outlets contain a wide range of product items. Rather than investigating all the different items it is appropriate in the initial cycle of analysis to focus on ‘Hot Products’. Following the path of these few ‘risky’ products through the supply chain can help to illustrate the general features of the process and the associated problems. ‘Hot products’ is a concept that many retailers and manufacturers are intuitively familiar with, and generally refers to those products most attractive to thieves. If retailers and manufacturers were to gain a better idea of what makes a product ‘hot’, then this could, by reducing the levels of the theft element within stock loss, help dramatically to reduce levels of shrinkage within the whole supply chain.

CASE STUDY EXAMPLE 2

Analysis undertaken on the Sainsbury’s case study clearly revealed the distinctive profile of losses concentrating on particular products. Efforts were then directed onto the small number of Hot Products in order to maximise the effectiveness of the investigation.

In categories suffering relatively little theft it is also possible to isolate a small number of items that account for a disproportionately high level of loss. This is true in bakeries for instance, where some items are particularly susceptible to damage as well as cooked meats where demand for particular items is volatile and therefore cause problems with stock going out of date.

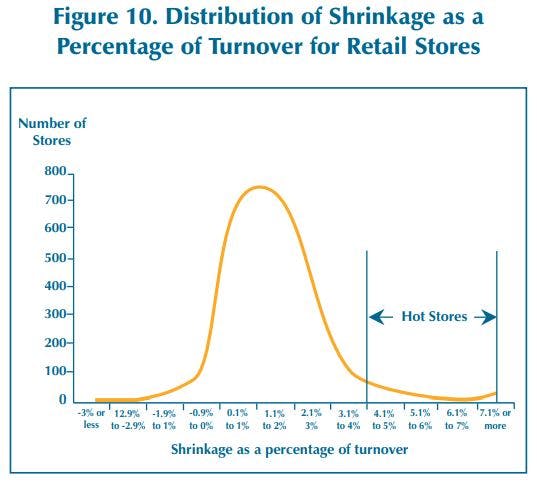

The concept of Hot Stores mirrors that of Hot Products – within a retailers’ estate the level of shrinkage is rarely evenly spread. Research commissioned by ECR has found that losses concentrate in a small number of stores that suffer a disproportionately high level of shrinkage. This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 10, which shows the distribution of losses for a sample of European retailers.

Hot products is a concept that many retailers and manufacturers are intuitively familiar with – it is those products most vulnerable to loss

In this example, the average rate of shrinkage is 1.75%. The Hot Stores are those to the right of the graph, with shrinkage levels considerably higher than the average. The objective of any business is to not only move the average figure further to the left of the graph, but to also reduce the number of stores generating rates of shrinkage above and below the average.

The social geography of a store’s location is likely to be a significant factor that affects the level of shrinkage. However, other factors are at least as important, for example, the competence of the store manager.

‘Good stock loss results follow good managers’ John Purnell, Director of Group Loss Prevention and Security at Tesco

Applying management attention to the disproportionately high level of shrinkage in Hot Stores by bringing their processes and procedures under control is likely to deliver significant benefits. Combining this focus on Hot Stores with a focus on Hot Products can help to maximise the return from investing in a shrinkage reduction project.

Hot Spots in supply chains are the steps where process robustness is at its poorest. Not only do losses occur by accident at Hot Spots but also the lack of control allows malicious loss to occur without detection or sanction. Identification of Hot Spots is achieved by undertaking a thorough risk assessment of the supply chain, paying particular attention to where product ownership transfers between internal functions and between organisations.

Capture and Share Best Practice

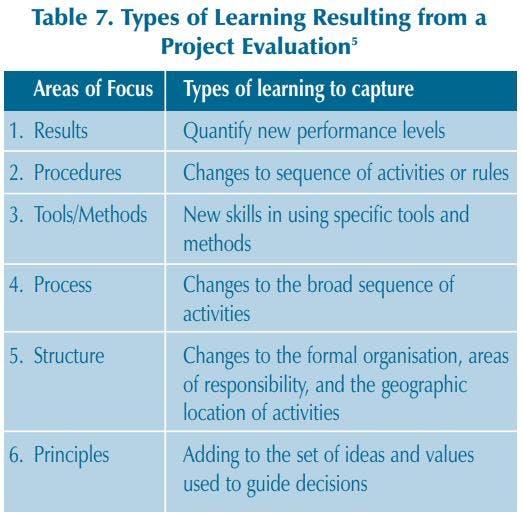

Practices implemented and used to address shrinkage should be assessed to determine their effectiveness. This can take a number of forms, with the most robust being to determine the impact of a practice on the metrics described previously. Where something is found to be effective, learning points should be distilled and then disseminated across the organisation. This is particularly true when assessing pilot projects in order to transfer the learning points across a wider geographic area or to other products. In the case of a retailer, best practices can be applied across the estate and to a range of suppliers. For manufacturers this roll out could be extended to other lines in their product range and the implementation of best practice across other retail accounts in other countries.

Deploying Policy in a Structured Way

More remarkable than the amount being lost by the FMCG industry each year is the fact that this situation has been allowed to continue unchallenged for so long. Shrinkage has been a significant blight on the FMCG industry throughout modern times and little has changed in recent years.

CASE STUDY EXAMPLE 3

Whilst today’s losses are a significant drain on profits, the key issue is the failure of current approaches in stemming this loss, a point well made by Allan Cheesman at Sainsbury’s:

‘Stock loss has been a ‘cause célèbre’ for over twenty-five years.’

Allan Cheesman, Head of Beers, Wines and Spirits, J. Sainsbury’s PLC

The resilience of shrinkage to existing methods should therefore come as no surprise. The reason being the poor quality of the approach used to tackle the issue.

The ECR Shrinkage Reduction Road Map provides a structured approach to collaborating with supply chain partners on loss reduction projects. The principle advantage of the Road Map is the focus it provides. This allows significant improvements to be delivered, as demonstrated in the case studies that accompany this Blue Book.

The Road Map is capable of delivering results in compressed timeframes (often as little as a few weeks), even when deployed by teams of people who are not improvement ‘experts’. These impressive results are achieved by incorporating a series of simple, effective tools within a structured series of steps that the team can put to work quickly and easily.

The ECR Road Map provides a structured approach to collaborating with supply chain partners – it is capable of delivering results in compressed timeframes using a series of simple and effective tools

Recognise Need for Ongoing Improvement

Key to successful integration of shrinkage reduction into corporate policy is to ensure that: gains identified by the deployment of the Road Map are sustained; best practice is propagated; and further improvement sought on an ongoing basis.

Making significant inroads into the opportunity to deliver better service to shoppers and streamline operations requires time and effort. Hence improvement projects need to be undertaken on an ongoing basis. Such projects involve a combination of:

- ‘Holding the gains,’ i.e. maintaining benefits by ensuring compliance to procedures and practices designed to prevent loss.

- ‘More of the same’ i.e. disseminating best practices identified by project teams.

- ‘Innovate and adapt’ i.e. respond to new threats and opportunities.

The learning gained through undertaking ongoing improvement efforts provides an important input to policy development, and highlights the need to develop the corporate policy itself over time. For example the underlying causes of shrinkage are dynamic, which means that the metrics used to track it may need to change over time in line with prevailing threats and opportunities.

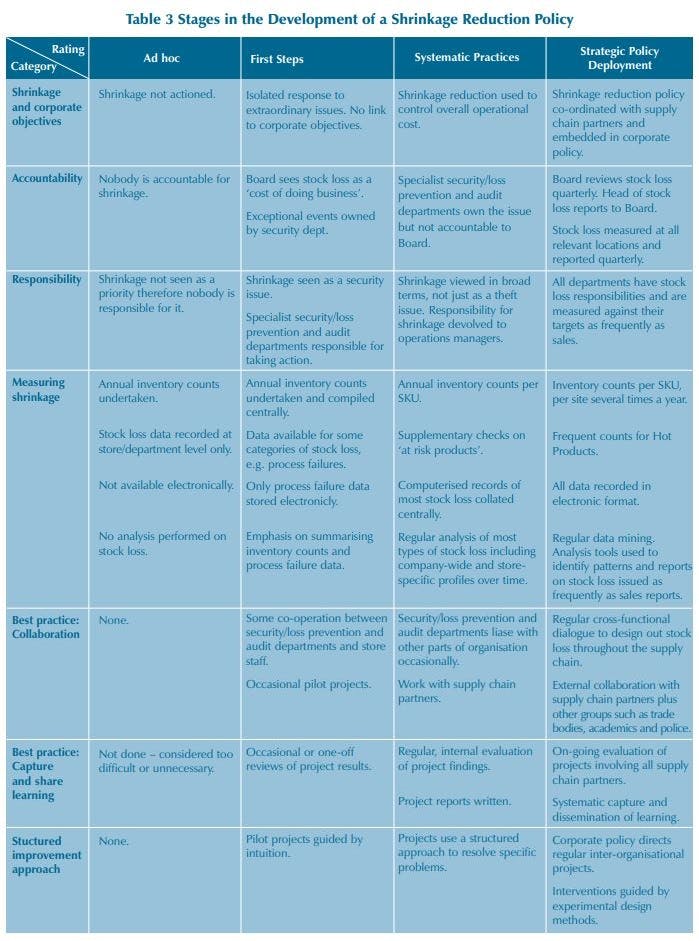

To help organisations review and develop their overall approach to stock loss reduction Table 3 provides a benchmarking tool to gauge the adoption of practices. This ‘look in the mirror’ is an important step in recognising how the overall shrinkage policy compares against best practice, as well as identifying the gaps between what is presently done and what needs to be achieved in the future.

The Shrinkage Reduction Road Map

At the heart of every corporate policy lies a framework for improvement. The ECR Europe Shrinkage Reduction Road Map, ‘The Road Map’ acts like a manual, describing the overall activities that need to be undertaken in order to develop projects to reduce stock loss. It also provides an objective ‘common language’ to help communication between the various partners that come together as a team to mutually resolve shrinkage.

The Road Map consists of a general approach made up of the steps that need to be followed, together with techniques and tools to help undertake each phase and to deal with problems that may be encountered. The general approach that forms the heart of the guide is shown in Figure 11. This structure is systematic and provides the means for planning and undertaking stock loss reduction projects while guiding users to embrace the need for continuous improvement.

Stock loss reduction involves problem diagnosis and solution implementation. The essence of the guide is that through well-planned investigation, pressing needs are identified. These are followed by smallscale experiments that explore the stock loss problem, identify likely causes and develop appropriate solutions. Undertaking trials can then assess the effectiveness of solutions. Where a solution is found to be successful it can be incorporated in the company shrinkage policy enabling its dissemination and the standardisation of best practice.

Given the uniqueness of each business environment where stock loss occurs, a single, ‘right’ strategy for reducing stock loss does not exist. Whilst this guide provides a basic structure for practitioners, the approach needs to be tailored to match prevailing circumstances in order for it to be effective. Knowing the scope for variation, what does and does not work and the reasons why comes with learning through experience. It is important to recognise that reducing stock loss is a long-term and on-going learning process. Therefore, success comes from using the systematic approach to building the capability to identify and understand the causes of shrinkage and reinforce practices that reduce loss.

The approach described in this guide provides a means for involving all company employees in stock loss reduction. Widespread involvement provides knowledge of current practices, such as stock control, and helps build commitment that allow changes to be implemented. This involvement stretches from the analysis of the current supply chain and its performance through to process redesign, implementation and review.

To help undertake the steps of the general approach, a number of techniques and tools are provided many with supporting documentation contained in the accompanying CD. These techniques and tools have been chosen to aid communication and understanding. This list is not comprehensive and practitioners should introduce their own tools where they find them to be more useful.

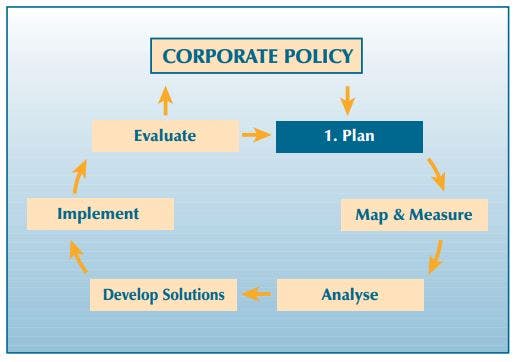

Step 1: Develop a Project Plan

Objectives

- Set a systematic approach to the project

- Identify and assemble project resources

- Undertake a stakeholder analysis

- St project goals

Set a Systematic Approach to the Project

Current efforts to contain and reduce stock loss are at best piece-meal, with few companies even operating an organisation-wide approach to resolving the problem. Companies need to recognise that traditional approaches, such as only tasking security, audit or health and safety departments with the challenge, are not effectual in tackling stock loss. Instead, companies need to change their approach to resolving stock loss and make use of a wider range of people. In changing their approach, companies need to choose one that is both systematic and holistic. A holistic approach requires involvement from stakeholders across a company and throughout the supply chain. Only through such collaboration can an effective strategy be developed for tackling shrinkage.

Identify and Assemble Project Resources

Effective stock loss reduction requires companies to be holistic by identifying, across the supply chain, where problems occur and can best be resolved. Such work requires collaboration along supply chains between suppliers, distributors and retailers as well as across the FMCG sector as a whole. Only when internal and external problems are considered together can comprehensive analysis be undertaken to deliver early, tangible results.

Undertake a Stakeholder Analysis

Having established the case for addressing the supply chain as a whole, the first step is to identify the key stakeholders in the supply chain. It is rare that any improvement project can be undertaken without an appreciation of social and cultural organisational dynamics. This is particularly true when seeking to reduce shrinkage as many of the concerns associated with it are ‘people’ issues.

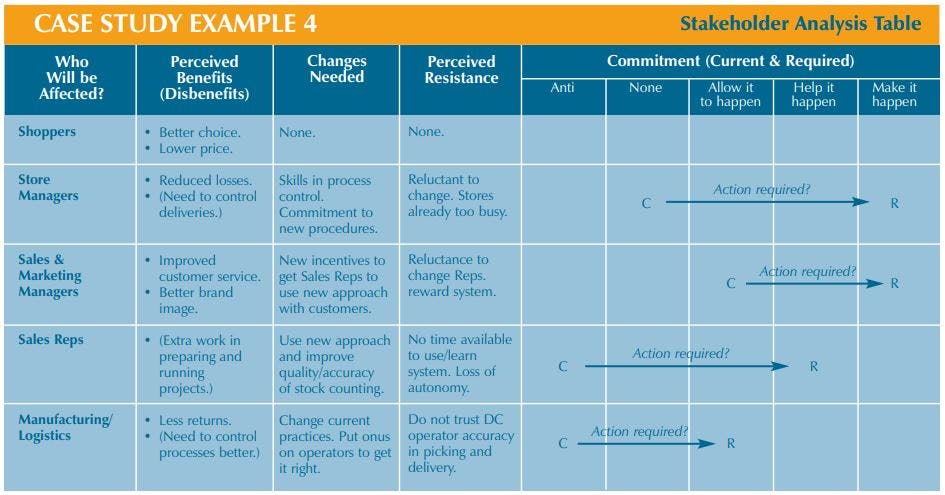

A stakeholder analysis identifies the people in an organisation and across the supply chain who will be affected by efforts to reduce shrinkage

Case Study Example 4 maps the effects that a loss reduction project will have on the stakeholders across a supply chain. The perception of the benefits and problems of these efforts are captured along with the various perceptions of the changes that will occur and the likely resistance to them. Finally, a judgement of current levels of commitment as well as those required to deliver the project is made. Efforts to resolve gaps between current and required levels of commitment must then be incorporated into the plan by the project team.

The results of the stakeholder analysis provide a valuable insight into which stakeholder groups need to be represented on the project team and where lines of communication need to be established.

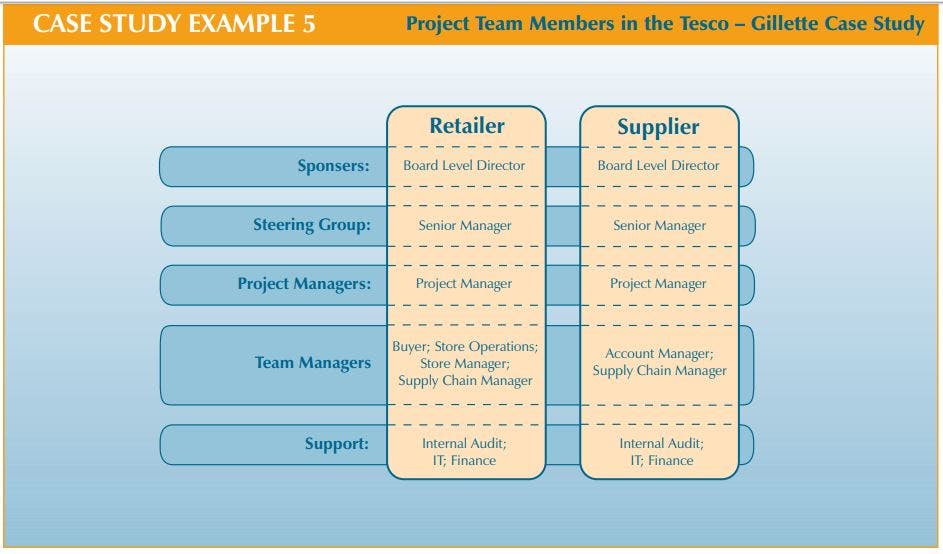

In the Tesco – Gillette case study, a stakeholder analysis helped to determine the make up of the project team. The various roles needed within the team are shown in Case Study Example 5, below.

This example shows the cascade of support from the sponsors of the project at director level, to the senior managers that lead the steering group and then to the project team itself. Whilst there are many people associated with the team, the bulk of the work falls to the project managers. These are the people tasked with delivering the project goals.

Set Project Goals

The final stage in the planning step is to set clear, realistic, attainable goals together with criteria for knowing when they are met. These goals are set by the project team who answer the following questions:

- What is the shrinkage problem?

- Where does the supply chain processes to be improved start and finish?

- What products are included in the investigation?

- What are the goals of the stock loss reduction activity?

- When is the date by which some benefits must be felt?

- What are the constraints to improvement?

The answers to these questions guide the project team’s activities towards achieving their goals. Starting the project in this way is especially important in cross-functional projects where the effectiveness and efficiency with which project resources are used dramatically improves with upfront investment in planning.

Planning for a project involves setting clear, realistic and attainable goals

Step 2: Map Key Processes & Gather Measures

Objectives

- Map key processes

- Gather measures

Reducing stock loss begins with a rigorous diagnosis of the problem. This starts by understanding the nature of the losses and then identifying their causes. Understanding the current operational system and processes is also important in gaining widespread recognition of the problem and establishing the need to change within an organisation. The act of creating a business process model that identifies the source of stock loss can develop the critical momentum required to change existing behaviour.

Security-led approaches to reducing stock loss tend to be based upon better detection of theft. A process-led approach applies process analysis to the stock loss problem and emphasises prevention. Traditional security strategies can therefore be supplemented by better understanding of supply chain processes. Process mapping and measurement provide the mechanisms to do this. Preventing system and procedural errors also removes the opportunities for theft that accompany deficient systems.

Map Key Processes

Documenting an existing process helps the project team view the various activities that make up a supply chain from a process perspective. Often, existing ways of working have never been described or even viewed as processes. Without the ability to communicate the need for improvement from this perspective, it can be difficult for some people to accept changes to the status quo.

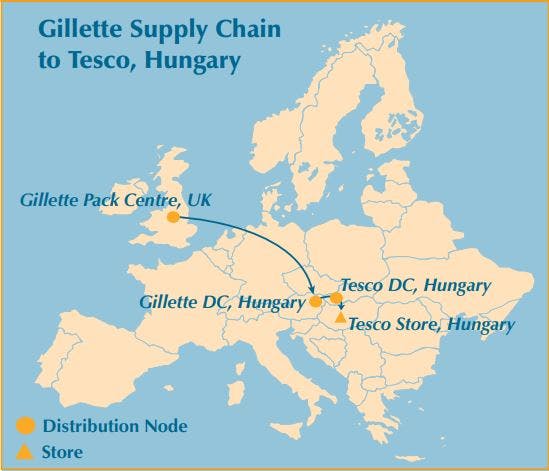

Process mapping is a technique used to: document a business process; focus on the important elements that influence behaviour; and allow the business to be viewed at a glance. Mapping and measuring a process establishes the performance base line that enables the effectiveness of solutions to be measured. An example of a top-level supply chain is depicted in Case Study Example 6. This diagram shows the supply chain from Gillette in the UK to Tesco in Hungary.

Whilst this example gives an understanding of the total supply chain, it provides few details. In order to acquire in-depth information on a process it is necessary to physically follow products as they pass along the supply chain. This involves visiting each site that the products pass through and documenting the steps involved in receiving, storing and dispatching them.

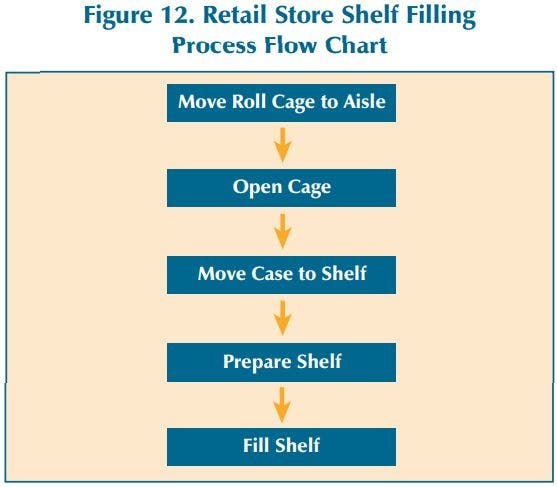

CASE STUDY EXAMPLE 6

Simple flow-charting techniques are the most appropriate way of documenting the steps of a process. When process mapping for the first time, the simplest and most effective flow-charting technique is to create a Block Flow Diagram. Figure 12 contains a block flow diagram that shows the steps involved in moving products in a retail store from backroom areas to the shelf. Where necessary, each of these process steps can be further analysed to document them to a higher level of detail.

There are many different ways that a process can be represented. These alternative methods can provide useful insights, however when communicating the findings of the process mapping exercise it is wise to keep the techniques as simple as possible. Even when the flow chart does not provide a complete or totally accurate model of a process it still has considerable value where it can promote a process-orientated approach to improvements and communicate understanding.

Gather Measures

Depending upon the current information systems within the company, the project team should employ two approaches to gathering measures to understand the problem they are trying to address. The first is to identify and collate relevant existing data available within the supply chain. The second is to collect new project specific data, which may include both ‘hard’ data such as statistics on particular incidents and types of loss, and ‘soft’ data such as interviews with staff or observations collected through site visits (the CD includes example data collection instruments that can be used to help project teams carry out this task).

As discussed earlier, there are a number of measures required to appreciate the Where? What? How much? and When? of stock loss.

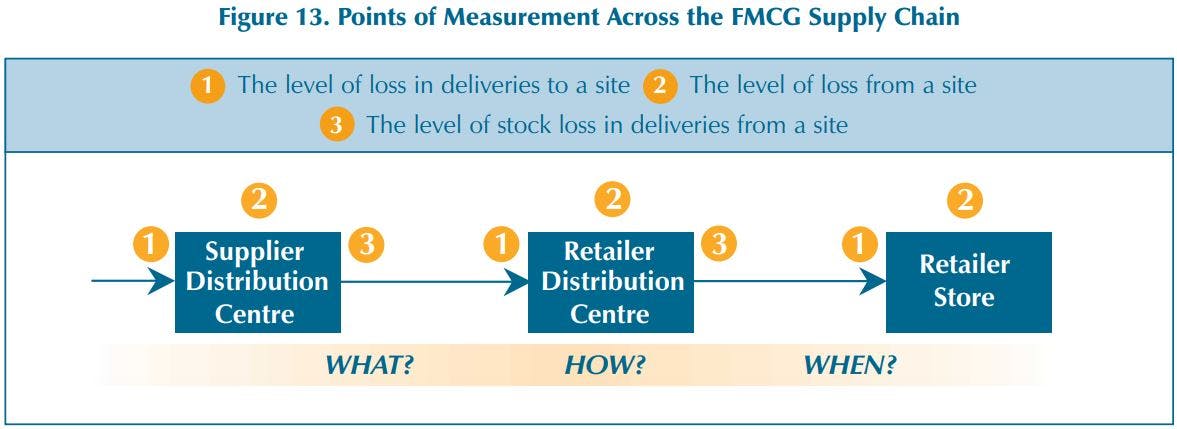

From a supply chain perspective, the following basic measures need to be collected:

- The level of loss in deliveries to a site.

- The level of loss from a site.

- The level of stock loss in deliveries from a site.

These measures allow a ‘top-level’ assessment of the extent and location of stock loss across a supply chain. In addition, it is necessary to collect data on the following factors:

- The type of incident, e.g. damage; out of date; or missing.

- How the incident occurred.

- When it happened.

This allows the nature of the type of stock losses suffered to be better understood. The points in the supply chain where these measures should be taken are shown in Figure 13. Companies need to develop an approach to data gathering that is systematic and part of an on-going process for collecting and collating timely and useful information that describes patterns, trends and information on stock loss throughout the supply chain – from first delivery to final check out.

Step 3: Analyse Risk and Identify Root Causes

Objectives

- Undertake a supply chain risk assessment

- Identify root causes of process failure

The information gathered through the mapping and measuring exercise provides an understanding of the supply chain. In order to make the best use of this information the ECR approach entails conducting a systematic risk analysis of the supply chain, identifying all the potential failures that could occur for each process step. These potential failures are documented and then each one is scored to determine its relative priority. The potential failures with the highest score are the Hot Spots in the supply chain. The Hot Spots are prioritised for further analysis, where their root causes are identified.

Undertake a Supply Chain Risk Assessment

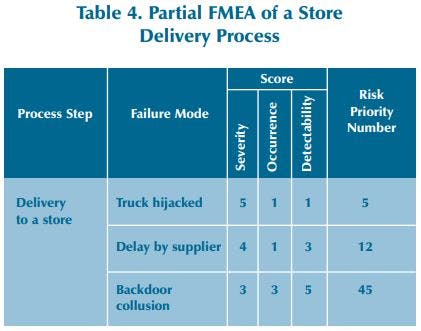

Supply chains are made up of many individual steps where each step and the handovers between steps are points where failure can occur. At each point there are several different modes (ways) for failure to happen. Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) is a technique that helps structure an assessment into the way a process can fail.

Each step in the process is examined and all the different potential failures associated with it are documented. A brainstorming exercise by the project team and specialists from across the supply chain is usually the most effective way of identifying all the failure modes.

A spreadsheet-based template for conducting the FMEA is provided in the accompanying CD-ROM

Having identified as many ways as possible that the process can fail, the risk associated with each failure mode is quantified. The scoring of risks considers the following criteria:

- Severity – the size of the loss, should a failure occur.

- Occurrence – how often the loss occurs.

- Detectability – how easy it is to detect loss.

Measuring the effect of a failure in terms of its ‘severity’ and ‘occurrence’ comes fairly intuitively to many people. However, the third criterion of ‘detectability’ is a little more difficult to judge but is as vital as the other two criteria to the risk assessment. The less detectable that a failure mode is, the more of a risk it presents. Undetectable failures cannot be resolved at the time they occur. Often they are detected at a much later time, if at all. The result is that the failure mode remains and the associated stock loss continues. When a thief or fraudster finds that losses are going undetected they are presented with an ideal opportunity to commit crime, which will also go undetected.

In the example below, some of the risks associated with a store delivery are assessed (Table 4).

In this example, three risks associated with a delivery to a store were identified and then scored against the three risk criteria using a scale of 1 (low) to 5 (high). In this example the truck hijacking was ranked as being the most severe, however it occurred very rarely and was considered as being very detectable. Multiplying the scores together gave this failure mode a relatively low risk priority number. In contrast, backdoor collusion at the store where goods are signed for but not delivered was thought to be moderately severe but occurred fairly often. This problem was also very hard to detect so this failure mode ended up with a relatively high risk priority number.

The highest scores calculated during the risk assessment for the supply chain as a whole reveal the ‘Hot Spots’. These Hot Spots are the points in the supply chain that present the greatest risk of loss. They are therefore prioritised for further investigation to determine their root causes. This is undertaken using the two tools of cause and effect analysis and 5-why analysis, described below. The cause and effect and 5-why analysis are repeated for as many Hot Spots that the project team has the time to investigate.

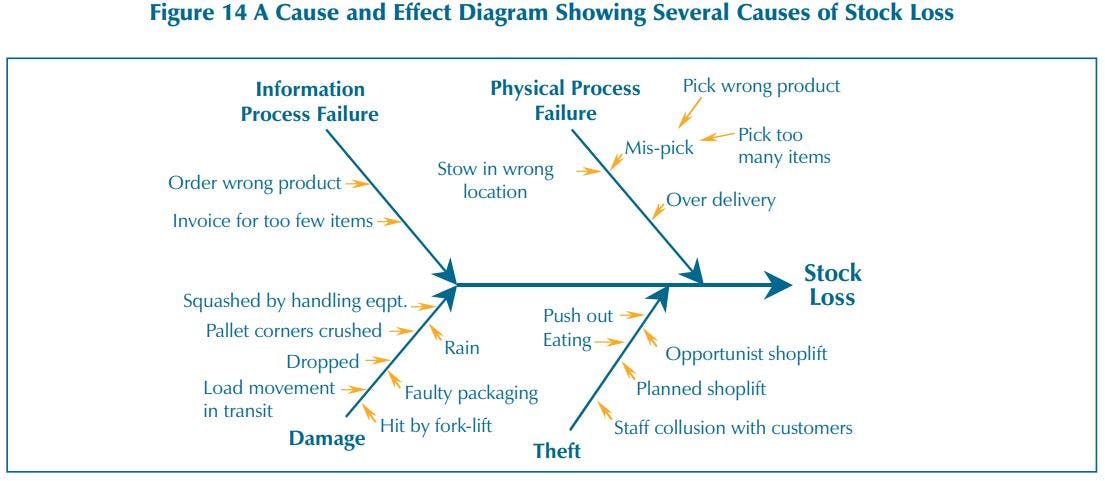

Identify Root Causes of Process Failure

A range of individual problems, as well as interactions between problems can cause supply chain Hot Spots. In order to reduce losses, a cause and effect analysis is undertaken on each Hot Spot. In keeping with the ECR principle of collaboration, the cause and effect analysis is once again a team effort. A further brainstorming session allows everyone to contribute their findings, experience and understanding. The key to the analysis is for the project team to repeatedly ask themselves variations around the question; ‘How/why/when does process or procedural failure occur at this Hot Spot?’ An example of the results from a cause and effect analysis is shown in Figure 14.

When the brainstorming is over, it is common for a team to identify a considerable number of ideas on what causes a Hot Spot. To focus effort, the key causes of failures need to be identified from amongst the trivial many. This could be achieved statistically through the collection of data from a process using check sheets to determine the number of incidents associated with each of the causes that have been suggested. However, it is possible to get the project group members to identify many of the most significant problems from their experience. The review by the team members should aim to identify between three and seven key issues from amongst the individual ideas. These issues should capture the essence of what is causing the Hot Spot.

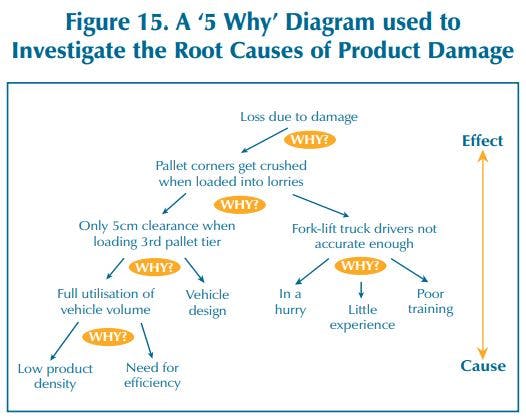

Often, the themes that are identified are themselves symptoms of other, more fundamental problems. It is therefore necessary to investigate further and identify the ‘root causes’ of the problem. In order to do this, the ‘5-why’ analysis tool is used.

5 Why Analysis

Initial ideas about the causes of problems are unlikely to identify underlying root causes. Having filtered the initial ideas and focused upon the significant ones, deeper cause and effect structures need to be identified. A technique to explore causes beyond those first perceived is ‘5 why’ analysis. This involves understanding the cause and effect relationship as fully as possible by repeating the question, ‘Why?’ This technique is illustrated in Figure 15 where the root causes of loss due to damage are investigated.

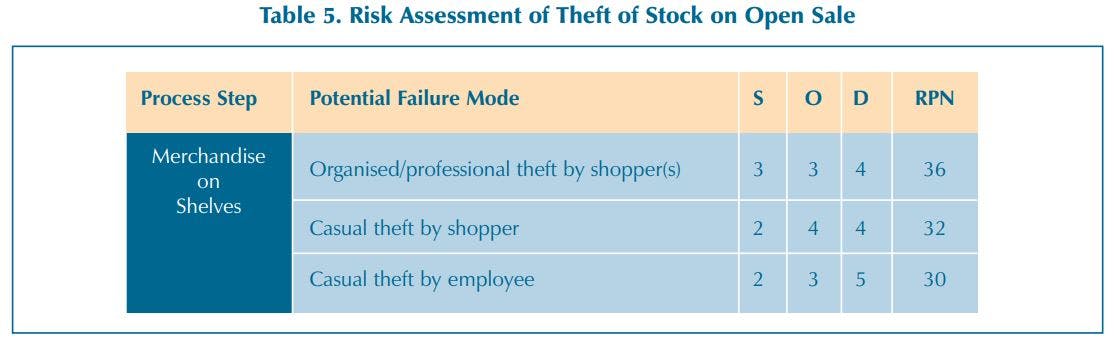

Using Risk Assessment to Address Theft

Risk reduction using FMEA and cause and effect analysis is a common approach to ensuring manufacturing processes conform to specification and is a significant help in reducing shrinkage caused by process failure, as described above. It is also well placed to help structure efforts to reduce shrinkage caused by theft as the following example aims to demonstrate.

A risk assessment was undertaken for a retail store, focussing on the risk of theft of a Hot Product line that was merchandised on open sale. The results are shown in Table 5 below

The problem of stock loss is dynamic – companies need to continually analyse the threat

All three of the potential failure modes were found to have a relatively high risk priority number, justifying further investigation into the root causes of these risks. A brainstorming exercise was conducted with people from store operations and the Loss Prevention team who contributed their ideas on the causes of off-shelf theft. The results of this exercise were filtered, identifying three key issues concerning product attributes, the location of the product in the store and the quantity of stock held on the shelves. Each issue was further analysed using the 5-why technique to uncover the root cause of the problem.

The result of this exercise was to highlight several root causes that were increasing the risk of theft from the shelf. Having diagnosed the problem and identified the root causes it is now possible to seek appropriate solutions to reduce risk.

End Note

Identification and understanding of root causes concludes the diagnosis of the causes of stock loss and starts the ‘remedial journey’, where solutions to these problems are sought. It is important to stress however, that the problem of stock loss is dynamic, particularly when considering the threat from internal and external thieves. Companies need to continually analyse the threat in order to react promptly to new approaches adopted by offenders.

Step 4: Develop Solutions and Prioritise Actions

Objectives

- Design solutions that reduce risk

- Balance solution cost against projected benefits

Organisations traditionally start their stock loss reduction efforts at this, the solution stage. It is not uncommon to find a great solution and then search for a problem to apply it to, particularly given the large number of seductive solutions currently available. However, this is totally at odds to the systematic approach advocated here. Having been through the diagnostic investigation described in the Road Map, where a stock loss problem has been investigated and its causes identified, it is usually clear that the solutions that resolve these causes and hence reduce loss are extremely context-specific.

Bearing in mind that the effectiveness of specific solutions is extremely context-specific, it is not possible in this book to associate particular solutions with particular problems. However, a series of options are presented in the CD that accompanies this book. The 68 solutions listed have been grouped into four different types: procedures and routines; design and layout; equipment and technology; and people and processes. It is not an exhaustive list of possible stock loss reduction options and many other possible solutions are currently available. The solutions are listed in alphabetical order and no attempt has been made to ‘rate’ their effectiveness.

Designing Solutions that Reduce Risk

The supply chain risk assessment described earlier helps the project team to identify specific actions to reduce the risks they have identified. This is possible because during the risk assessment, the failure modes were assessed against the three criteria of Severity, Occurrence and Detectability. High scores against one or all of these criteria point the team to where actions need to be taken. These actions are usually context specific, for example, in the Gillette/Tesco case study, there was a supply chain Hot Spot where product could be lost when stored in the back of a store. Risks relating to detectability and severity of this failure mode were both assessed as being high. This pointed the project team to take action to improve the detectability of loss by introducing a daily stock count. The action taken to reduce the severity of loss was to minimise the amount of stock held in the back of the store and increase detectability through regular checks (See Case Study Example 7).

CASE STUDY EXAMPLE 7

The 10 steps are generic solutions developed by the Gillette Company in collaboration with its customers. In essence, it is a series of solutions designed to enable a retailer to more effectively increase product availability and at the same time reduce stock loss in their stores.

The core 10 steps are:

- Secure delivery: Separate out high risk products and deliver them in sealed pallets.

- In-store champion: Identify a member of staff to take responsibility for checking product movements.

- Fast tracking to secure area: The delivery area leaves products vulnerable – move them to a secure area as soon as they arrive.

- Check deliveries: Checking deliveries is important – mistakes show up as stock loss.

- Visible locations: Keep products on open sale but in highly visible locations.

- Anti-theft fixtures: Use fixtures that slow down the rate at which products can be removed.

- Appropriate replenishment: Stock shelves to match rate of sale – too much product tempts thieves, too little frustrates shoppers.

- Regular counting: Count high risk products regularly to track losses and allow accurate reordering.

- Staff awareness: Encourage all staff to be more vigilant.

- Measure and adjust: Measure the effectiveness of solutions, review and adjust the process accordingly.

Balancing Solution Cost Against Projected Benefits

Good solutions strike a balance between the benefits they deliver in reducing loss and the cost of achieving these benefits. In order to estimate this balance it is necessary to quantify the costs, both in terms of capital costs (such as buying equipment and training staff) and recurrent costs (such as maintenance or extra staff time).

The project team then need to calculate the benefits brought about through the introduction of the solution. For most projects this will be measured by the amount shrinkage is reduced and possibly increased sales. These benefits are likely to be recurring but may diminish over time depending upon the nature of the intervention. The project team needs to estimate what the likelihood is that the expected benefits will be sustained and over what time period.

COST BENEFIT EXAMPLE

Having investigated a supply chain, a project team identified a particular solution that removes one of the root causes of shrinkage for a Hot Spot. This solution has the potential to reduce shrinkage each year by €40,000. It is thought that 75% of this potential reduction can be realistically achieved in the first year. The team expects the effectiveness of the solution to decrease by 10% in subsequent years. The initial cost to implement the solution will be €20,000 and it costs €15,000 each year to keep operating the solution.

Year 1: Expected Benefit – Cost of Implementation = Net Contribution

(€40,000 x 0.75) – €35,000 = -€5,000

Year 2: Expected Benefit – Running Costs = Net Contribution

(€40,000 x 0.75) x 0.9 – €15,000 = €12,000

The overall net benefit is that the solution has both paid for its implementation and saved the company €7,000 within the first two years.

Step 5: Implement and Trial Solutions

Objectives:

- Develop implementation plans

- Implement solutions

In a similar manner to the approach used to plan the project investigation, the implementation of the solution that will reduce stock loss requires project planning. Successful projects require a sponsor to be responsible for delivering the benefits of the project. To achieve success the sponsor, usually a senior manager, needs to ensure that the project team constructs a clear and robust business case. This defines what is to be delivered, the benefits it will bring and the resources required.

The scale and scope of the solutions to be implemented varies considerably between projects however they tend to be variations around four main archetypes:

- Simple, quick and effective fixes

- Application of established best practice

- Experiments

- Business case pilots

Simple, quick and effective fixes (known in America as ‘no brainers’) are solutions that make good sense to be implemented straight away. Examples of these include ideas that the organisation thought it was already undertaking (such as re-establishing procedures that have lapsed); widespread application of ideas that are already tried and tested (such as regular counting); and low cost/no cost ideas that tighten up procedural adherence (such as refund policies).

The application of established best practice takes good ideas that are known to reduce risk and deliver profit improvement. Examples of this include controlling at-risk products the same way as established Hot Products such as cigarettes, cash and high value alcohol.

Experiments involve implementing seemingly good ideas that lack information on their effectiveness or potential impact on other aspects of the business.

The outcome in these implementations may not necessarily be to reduce shrinkage but to learn more about the solution itself. This may be thought of as a ‘shake down test’ of a piece of equipment or a particular process and above all as a learning opportunity.

Business case pilots trial ideas that are conceptually robust but where the data on which to make a cost/benefit analysis is lacking. The purpose of this work is therefore to assess benefits and costs of implementing the solution in an operational setting.

Develop Implementation Plans

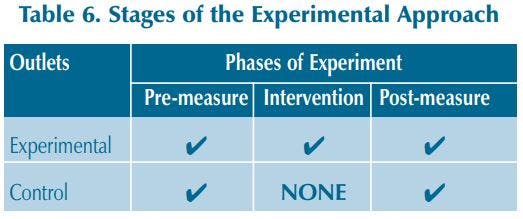

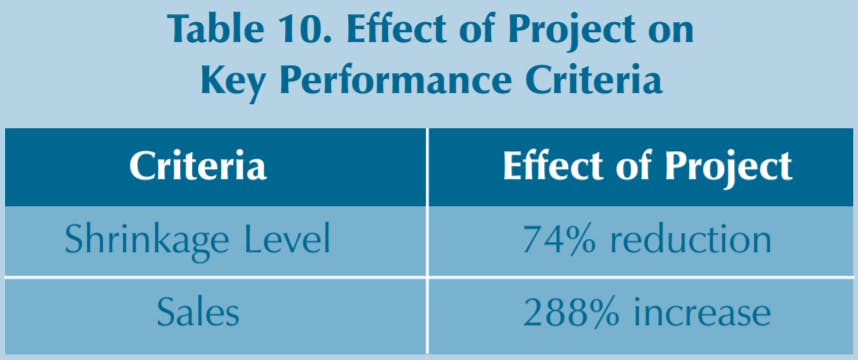

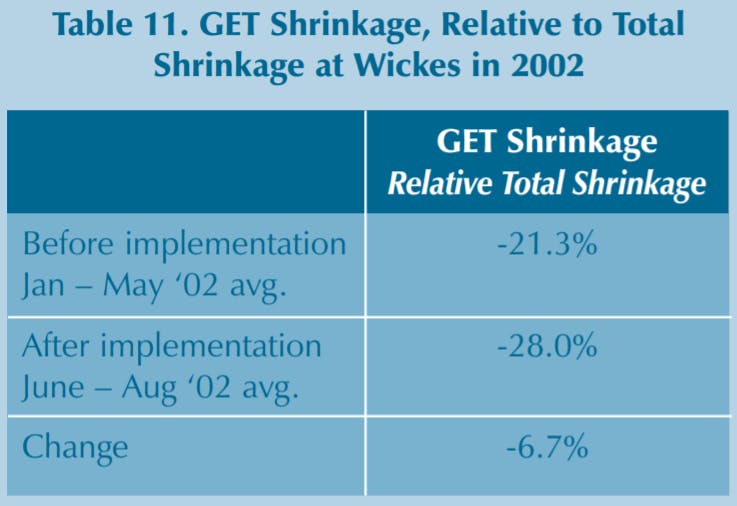

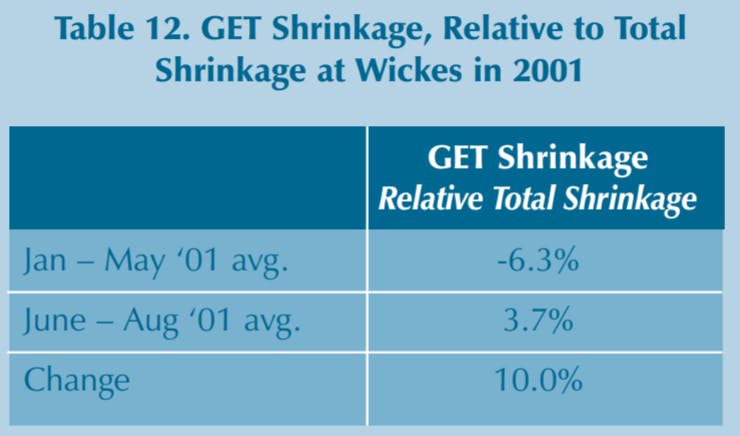

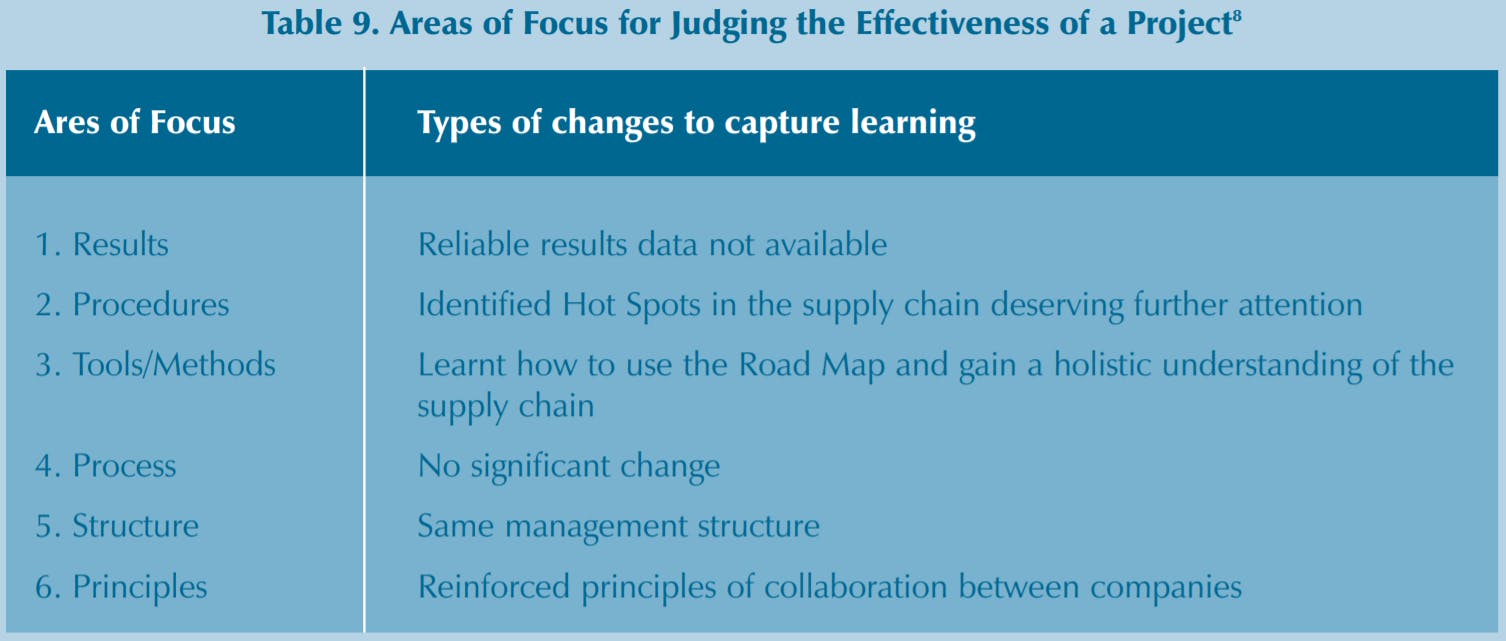

No matter what type of solution has been selected, an implementation plan helps ensure the desired objectives are delivered within time and cost limitations. Here the tools of project management will prove useful. These can be applied on both small and large-scale projects. Where a project team undertakes planned change for the first time, the plan should consider not just the task but also the learning necessary to deliver it.