Fortress Stores: Keeping the most-at-risk grocery stores trading

This research report outlines the findings from an in-depth study into ‘most-at-risk stores’, i.e. those with the highest rates of crime, threat and vulnerability. The project aimed to explore the risk mitigation strategies being deployed, their rationale, and how they are experienced by store associates.

Companies located in 11 different countries took part in interviews and more than 30 stores were visited in person in six different countries. Store associates, security guards, store managers, area managers, and even some customers took part in informal discussions and interviews relating to security and risk mitigation in each site. Initial findings were presented at international events and circulated to specific industry experts for comment. Feedback from these individuals and sessions has further helped shape this final report.

The research reveals that most-at-risk stores are typically comprised of intensified levels of the following:

- Violence and verbally abusive behaviour directed at store associates.

- External theft and theft from customers

- Homelessness, Transient Populations and Loitering

Risk Mitigation Wheel: 7 key strategies

The findings are presented as a framework designed to help retailers think about protecting their most-at-risk stores. The framework is comprised of seven elements: data, people, control, offenders, guarding, monitoring and joining forces. If nothing else, it is worth reflecting upon these categories; they might provide affirmation that your risk mitigation strategy is aligned with international approaches. Or they might just spark a new idea or approach to thinking about risk and how to counter it. The approaches in some locations are changing the mould and this might leverage engagement and support for delivering a successful risk mitigation strategy in some of the industry’s most challenging stores, particularly when it might be at odds with brand identity.

Although the tactics that sit within each of the 7 strategic principles might be different, the key point is about the extent to which the business is aware of risk, acknowledges the need to do things differently, aligns the different business functions, and enables specific actions to be taken.

- Awareness: To what extent is the store aware of the specific risks that are present?

- Acknowledgment: To what extent does the business acknowledge that the store requires special measures to manage the heighten risks?

- Alignment: To what extent has the business shifted practice to align with the security needs, particularly when this presents tensions with the overarching company brand and/or policy deployed elsewhere in the estate?

- Actions: To what extent is the business supporting and investing in concrete actions to mitigate risks?

A benchmarking tool is available for businesses to assess how well they are performing against the 7 key strategies and four levels of activity.

Foreword

We know that the current climate for bricks and mortar grocery stores is very challenging in some locations. This report documents in detail the many and varied issues that are present in and around stores; violence, verbal abuse, theft, organised retail crime, anti-social behaviour. It makes for a sobering read. But what is most illuminating about this report is its synthesis of how businesses are responding. There are strategies that are working to turn the tide on increased levels of violence and theft, but they involve creative thinking and sometimes tensions with the company brand. There are also areas identified where businesses could – and should – do better. Making it easier for employees to report incidents to the police and ensuring that accurate and timely data is collected, analysed, and acted upon is just one area where the industry could improve.

For those with responsibility for keeping colleagues safe and protecting assets, I strongly urge you to read this report, reflect upon the 7 strategies for keeping the most-at-risk stores trading and complete the Most-at-risk Stores Benchmarking Tool. It might be that some of the approaches are affirmative, some might not be possible due to local laws, but there might be some ideas or ways of doing things that are new. Additionally, the Benchmarking Tool might help to better identify where there are gaps, blockages and opportunities to evolve risk mitigation strategies and leverage engagement and support for delivering innovative strategies to combat risk.

I would like to thank Professor Emmeline Taylor for carrying out this research. With 11 countries participating, six of which were visited in person, it is by far the most comprehensive and in-depth study conducted on this important topic. I would also like to thank CAP Index for the additional research grant that made this study possible.

As with all the research undertaken on behalf of ECR Retail Loss, it would not be possible without the active support and involvement of the retail community and the many employees who generously gave their time to participate in the most meaningful of ways. Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts and experiences – by working together we are much more likely to Sell More and Lose Less!

Finally, can I encourage you to not only read and share this study, but also take part in the work of ECR Retail Loss – further details can be found at: www.ecrloss.com.

John Fonteijn

Chair of the ECR Retail Loss Group

Acknowledgements

This research would not have been possible without the generous participation of the individuals who took part in interviews and their companies who agreed to host multiple store visits. I am also thankful to the many store associates, security officers, store and area managers, as well as customers who also contributed by taking part in informal interviews and discussions and sharing their insights and experience. All participants talked candidly about the issues that they face on a day-to-day basis. The research was made possible by an additional research grant provided by CAP Index. I would also like to extend gratitude to the 65 participants at an ECR Loss working group meeting in March 2023, the 128 attendees at the FMI Asset Protection and Grocery Resilience Conference in the USA in April 2023, and the specific industry experts to whom an earlier draft was circulated, for providing incredibly valuable feedback and discussion that has further helped to shape this final report.

Executive Summary

Background

Grocery retailers are facing unprecedented levels of in-store risks including frequent violent and verbally abusive attacks on employees and increases in the value and volume of thefts. These issues are occurring within a broader social context of a challenging economy, homelessness, drug and alcohol misuse and politically driven civil unrest that can lead to looting and criminal damage. Furthermore, there are ongoing difficulties in employee recruitment and retention. High vacancy rates and persistent staff turnover create additional problems. Experienced and trained employees are leaving the sector and recruitment remains challenging. Low levels of training and experience amongst new recruits, alongside understaffing only exacerbate the risks.

Although there are some positive examples of the police collaborating with retailers to tackle crimes affecting their business, overall, the view is that law enforcement is unresponsive to the issues and retailers describe feeling ignored and even “abandoned.” There are also many examples of criminal justice policies introduced with the good intention to relieve pressure on buckling systems but that bring with them unintended consequences for retail crime by effectively downgrading the seriousness of theft or allowing organised repeat offenders to avoid prosecution.

It is hard to think of a more challenging trading context for grocers and it is driving some stores to the brink of closure.

The research project

This research aimed to identify what security solutions (technological, design-based and humanistic) are being deployed by grocery retailers in their most-at-risk stores, i.e. those with the highest rates of crime; to explore the rationale for deploying the selected solutions from the perspective of Heads of Security/Loss Prevention, and; to gain an understanding of how the security response is experienced by store staff (in terms of usability, effectiveness, performance, issues etc.).

To meet these aims, an in-depth study was carried out that involved 25 interviews with 34 participants representing companies located in 11 different countries.2 Multinational in-person store visits were made to some of the most-at-risk stores identified by participating businesses. More than 30 stores were visited in person in six different countries.3 Store associates, security guards, store managers, area managers, and even some customers took part in informal discussions and ad hoc interviews relating to security and risk mitigation in each site. An initial draft of the findings was presented for discussion at an ECR Loss working group meeting in March 2023 attended by 65 retailers, circulated to specific industry experts for comment, and presented in the USA at the FMI Asset Protection and Grocery Resilience Conference in April 2023. Feedback from these individuals and sessions has further helped shape this final report.

Identifying the most-at-risk stores

Despite the growing range of risks present in-store, the research found very few businesses had a robust system for reporting, collating, analysing, and using accurate and up to date data to inform risk mitigation strategies. Even fewer were using data to predict the location of problematic stores or to enable the linking of repeat offenders across multiple locations. A lack of data not only makes it difficult to develop effective countermeasures, but it also hinders the ability to disrupt prolific criminal gangs.

Characteristics of most-at-risk stores

Grocers report that their key vulnerabilities and threats in most-at-risk stores are typically comprised of intensified levels of the following:

Violence and verbally abusive behaviour directed at store associates. The main scenarios in which this happens relate to encountering thieves and the enforcement of legislation relating to the sale of age-restricted goods and other prohibited sales. Less frequent but devastating is hate and ideologically motivated incidents (including armed active assailants) and robberies.

External theft in most-at-risk stores occurs at a heightened volume and frequency. Two types of theft are currently of particular concern: self-service checkout theft and emergency exit ‘push outs.’

Homelessness, Transient Populations and Loitering are major concerns in the most-at-risk stores. This can present multiple problems for retailers relating to littering, obstructing entrances and exits, aggressive behaviour, antisocial behaviour and signs of drug use.

Theft from customers, typically taking place in the parking lot, offenders use a range of distraction techniques to steal from customers and/or their vehicles. Some thieves operate inside the store, stealing personal items that have been left momentarily unattended in shopping carts.

While some issues are more pronounced in certain markets and rates of crime might vary by country, the increased cost of responding to physical security threats and vulnerabilities is universal. Not only are these costs incurred as a direct result of crime (stolen goods, lost working hours, criminal damage, etc.), but companies report that expenditure on security and preventative strategies is increasing across the sector.

How are businesses responding in their most-at-risk stores?

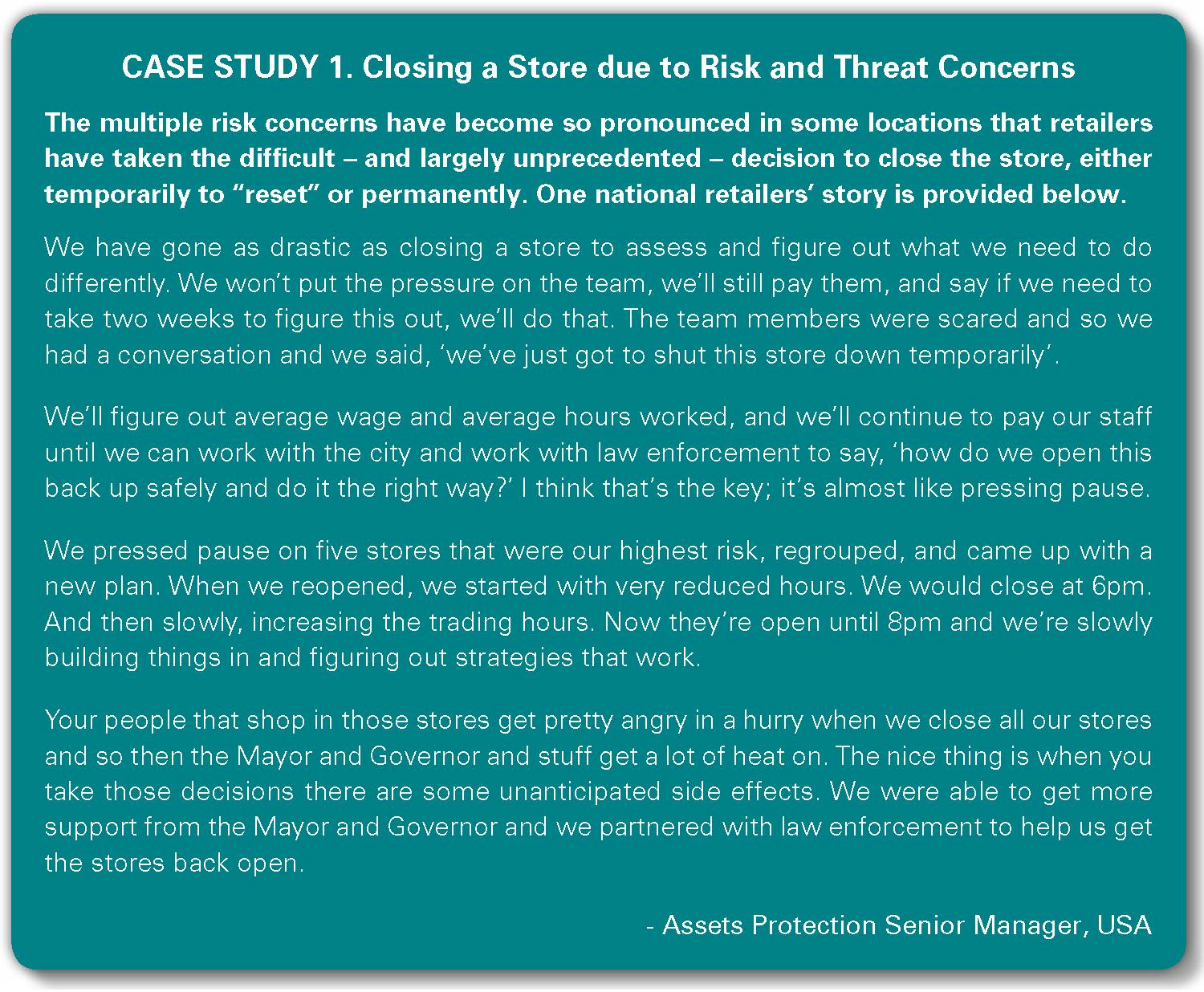

It is no secret that some businesses are permanently closing stores in their most-at-risk locations. High-risk and low-profit stores are balancing a need to protect people, assets, and reputation. This balancing act is not without tensions; there are social and political implications as well as reputational risks for security and operational decisions in some markets, particularly those in deprived neighbourhoods. The closure of stores in some locations can remove vital services such as medical supplies, contribute to unemployment rates, and even create ‘food deserts’ where local people cannot access affordable fresh produce within a reasonable distance.

A step back from permanent closure is a concerted effort to exert heightened levels of control over every aspect of the store operation using a mix of technology, design, operational strategies, and people. For some companies, applying a ‘fortress store’ mentality was a last attempt to keep trading in some markets that had become increasingly hostile. This includes changing trading hours, merchandise assortment, locking more produce away, tagging more products, enhanced and innovative guarding strategies, reconfiguring layouts and transforming store design. At times, the security strategy applied in most-at-risk stores was at odds with the broader direction of the company and its brand. There are difficult discussions taking place about how best to protect employees and assets while maintaining brand reputation and profitability

Strategies are not always straight forward or easy to implement across the estate. Big-box stores, retrofits and other formats are often not designed to be operated with the enhanced levels of control that is needed to manage high-level risks. There is no ‘one size fits all’ recipe.

Health and safety regulations and other legislation present additional challenges; prolific thieves take advantage of emergency exits to escape, employees are required to enforce a range of rules relating to public health and restricted goods (e.g. Covid-19 and alcohol laws) which can create ‘flashpoints’ for violence, and some thieves now flaunt their stealing to store associates knowing there is a ‘no challenge’ company policy in place.

Keeping most-at-risk stores trading: 7 key strategic principles

The findings are presented as a risk mitigation wheel designed to help retailers think about protecting their most-at-risk stores. The wheel is comprised of seven elements: data, people, control, offenders, guarding, monitoring, and joining forces. If nothing else, it is worth reflecting upon these categories; they might provide affirmation that your risk mitigation strategy is aligned with your current approaches. Or they might just spark a new idea or approach to thinking about risk and how to counter it. The approaches in some locations are changing the mould and this might leverage engagement and support for delivering a successful risk mitigation strategy in some of the industry’s most challenging stores, particularly when it might be at odds with brand identity.

Although the tactics that sit within each of the 7 strategic principles might be different, the key point is about the extent to which the business is aware of risk, accepts the need to do things differently, aligns the different business functions, and enables specific actions to be taken.

- Awareness: To what extent is the business aware of the specific in-store risks and vulnerabilities?

- Acceptance: To what extent does the business accept that the most-at-risk stores require special measures to manage the heighten risks?

- Alignment: To what extent has the business shifted practice to align with the security needs, particularly when this presents tensions with the overarching company brand and/ or policy deployed elsewhere across the estate?

- Actions: To what extent is the business supporting and investing in concrete actions to mitigate risks?

Most-at-risk Stores Benchmarking Tool

The Most-at-risk Stores Benchmarking Tool can be found on page 45. Businesses are encouraged to complete the tool by responding to a set of four statements for each of the 7 key strategic principles. The questions relate to the degree of awareness, acceptance, alignment, and commitment to act on issues experienced in most-at-risk stores.

The benchmarking tool will provide a score for each category (data, people, control, offenders, guarding, monitoring and joining forces) as well as across the four levels of activity: awareness, acceptance, alignment and actions, to provide clear insight to what aspects are working well and which require further attention.

Introduction

Retailers are facing multiple in-store security-related challenges and risks. Frequent violent and verbally abusive attacks on employees continue to be a major concern. This includes violence relating to theft; hate motivated incidents (including armed active assailants), robberies, and enforcing legislation relating to the sale of restricted goods (e.g. alcohol and bladed articles). Some challenges, such as theft, have always been a threat to contend with, but the volume and value of theft incidents has shifted gear as organised retail crime gangs mobilise efforts across states and countries. In addition, newer threats have emerged such as ideologically motivated attacks playing out in business environments, and civil unrest spilling over into stores resulting in looting, lost trading hours, and criminal damage. There are also many confronting social issues presenting in and around grocery stores that associates are typically ill-equipped to manage. For example, homelessness, drug and alcohol misuse, antisocial behaviour, and poor mental health within the community. A concentration of these risks is driving some stores to the brink of closure.

Research Aims and Objectives

Despite the heightened risks and the huge financial costs, there is relatively little shared knowledge about how retailers are responding to keep their most-at-risk stores trading. This report presents findings from a study that focused on understanding how grocers seek to mitigate risks in their most vulnerable locations, how they go about balancing profitability with a need to protect people, assets, and reputation, and, how store associates respond to interventions.

The research had three main aims, to:

- identify what security solutions (technological, design-based and humanistic) are being deployed by grocery retailers in high-risk stores, i.e. those with relatively high rates of crime (including theft, assaults against staff, and/or robberies) in multiple countries;

- understand the rationale for deploying the selected solutions from the perspective of Heads of Security/Loss Prevention, and;

- gain an understanding of how the security response is experienced by store staff (in terms of usability, effectiveness, performance, issues etc.).

Methodology

To meet these aims, a comprehensive and in-depth study was carried out with a total of 24 different businesses participating. The methodology involved the following:

- Interviews were conducted with 34 participants representing 24 companies located in 11 different countries.4 Interviews were conducted with a range of individuals and role types, including Heads of Security and Loss Prevention Managers.

- Multinational in-person store visits were made to some of the most-at-risk stores identified by participating businesses. The visits focused on observing firsthand the challenges that the store was experiencing as well as seeing the security strategies in situ. More than 30 stores were visited in person in six different countries (Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, the UK, and the USA). Multiple businesses took part in some locations e.g. six different businesses participated in the USA store visits. Store associates, security guards, store managers, area managers, and even some customers took part in informal discussions and ad hoc interviews relating to safety and security concerns and risk mitigation in each site.

- Industry expert feedback. An initial draft of the findings was presented for discussion at an ECR Loss working group meeting in March 2023 attended by 65 retailers, circulated to specific industry experts for comment, and presented in the USA at the FMI Asset Protection and Grocery Resilience Conference in April 2023 attended by 128 delegates. The valuable feedback from these individuals and sessions has further helped to shape this final report.

- Literature review. A comprehensive review of available industry reports and academic research published in the English language was undertaken. Businesses from 8 non-native English-speaking countries participated in the project. We have tried to incorporate as many examples of data from these countries as possible but it is often not readily available. It should also be noted that often the data underpinning non-academic reports is not available for scrutiny and therefore the robustness of the claims, particularly relating to the frequency and volume of crime incidents, should be taken with caution. This caveat further underscores the need for businesses to collect the most accurate, detailed and timely data as possible.

Structure of the report

The following section, ‘Most-at-risk Stores: risk and threat priorities’, outlines the main issues experienced in most-at-risk stores. While some of these concerns might also be present in lower risk stores, the emphasis here is on the frequency, volume and scale which catapults the store into the ‘most-at-risk’ status.

Section 3, ‘Fortress Stores: keeping the most-at-risk stores trading’ outlines a snapshot of the approaches being taken internationally to respond to different risks in the grocery sector. The findings are presented as a framework comprised of seven elements: data, people, control, offenders, guarding, monitoring and joining forces. They represent the top-level tactics and approaches applied in the most-at-risk stores and locations. Again, some of these approaches might be very familiar in some locations, others might not be possible due to the legal context, but overall, as a framework, there were very few businesses that were actively adapting in all seven areas. The Most-at-risk Stores Benchmarking Tool on page 45 enables businesses to explore how they are performing across the 7 key strategic principles.

It is important to highlight that the law is different in each country (and sometimes across jurisdictions in the same country). This goes some way to explaining the varied deployment of security solutions, particularly pronounced for audio-visual technologies such as body-worn cameras (BWC), and facial matching. There are also cultural differences which underscore customers’ tolerance of and appetite for different security procedures and technologies. Furthermore, the research did not set out to establish the effectiveness or ROI of each technology or process beyond a company’s own perception of it. Rather, the aim is to document the approaches being taken across the international landscape to provide affirmation, inspiration, and leverage to support difficult conversations within businesses.

Most-at-risk Stores: risk and threat priorities

I have never seen levels of theft as high as they are now. When the offender no longer cares if you see them stealing or not or they think the risk is worth the reward, that is a scary place to be. Companies are having to take more and more extreme measures. In some locations they are deciding not to stock some merchandise, or the cost is being driven up because the losses are so high. Some companies are closing stores entirely. That means that those communities have nowhere to go to buy their medicines, their groceries, etcetera.

(Assets Protection Senior Manager, national retailer, USA)

As outlined previously, we know that retailers are experiencing multiple and varied in-store security-related challenges. We asked grocery retailers to identify their top three concerns in their most-at-risk stores (see Table 1). Perhaps unsurprisingly, the safety of employees was the leading concern in most countries. All participants described an environment that was becoming increasingly hostile and one in which employees were experiencing heightened levels of violence, aggression, and verbal abuse. Concerns mostly related to guest-on-associate violence, the main triggers for which are explored below, but also other specific violent threats such as active armed assailants (particularly in the USA) and civil unrest (particularly France, the USA, and the UK to a lesser extent) which could manifest in looting or protests within the vicinity of the store.

Other prevalent risks identified as priority concerns included theft, particularly self-service checkout theft and emergency exit ‘push outs’; the issues generating by loitering, antisocial behaviour and large homeless populations congregating in and around the store; and theft from customers while on the premises (often associated with professional travelling thieves rather than opportunists). These four main concerns are outlined in more detail below.

Violence and Aggression

Violence can be customer on customer, customer on team member, team member on team member or some other factor in a team member’s life that could play out in the workplace where the potential attacker could be coming to the workplace to cause harm.

(VP Asset Protection and Safety, regional retailer, USA)

Multiple sources suggest that the frequency and severity of violent incidents in the retail sector have been increasing significantly.5,6 While this trend does not manifest in precisely the same way in each country, the overall perception is of an ever more aggressive working environment, particularly in densely populated urban areas.

Some of this increase was attributed to what was referred to as ‘organised retail crime’ (ORC) but it is important to note that there are different definitions internationally as to what constitutes ORC (see textbox below). Participants in this study described organised criminals as being more brazen, more willing to use violence, and more confrontational than other types of offenders.

In addition, there are other factors that are contributing to an increase in violence including a corresponding growth in opportunist theft, active armed assailants, gun and knife violence, and the requirement for store associates to uphold legislation and regulations associated with restricted items e.g. age-related sales, bladed items, alcohol and tobacco.

I’ve had people scream in my face because I accidentally rang an item twice.

(Store Associate, USA)

The threshold has definitely lowered for the use of violence.

(Chief Risk Officer, Finland)

Demonstrating the triviality of some situations that result in violent altercations, some shop workers reported that customers would become violent or abusive if merchandise was out of stock, they had accidently been charged the wrong amount, or other services in the store, such as ATMs, lottery machines, or bill paying facilities, were not functioning.

Organised Retail Crime: A note on definitions

There are different definitions of organised retail crime used internationally. For example, in some countries two or more persons stealing with the intention of selling on merchandise for financial gain is regarded as ORC. Whereas in other locations ORC is used to refer to largescale criminal enterprises that use techniques of criminal exploitation7 to force victims, usually vulnerable adults and children, to steal.

The scales of operation in these two descriptions are vastly different and the involvement of organised criminals in other activities such as trafficking, drug dealing, and modern slavery also sets them apart.

There is much more that needs to be done to establish universal working definitions of what ORC is, and how it manifests, if it is to be effectively targeted and disrupted.

The main triggers and scenarios in which violence occurred, as reported in this study, were:

- encountering thieves

- enforcing legislation relating to the sale of age-restricted goods and other prohibited sales

- hate and ideologically motivated incidents (including armed active assailants)

- robberies (including ‘flash mob’ robberies and ‘swarming’)

- mental health issues

Encountering thieves

Shop thieves are increasingly resorting to violence, threats, intimidation, and abuse directed at staff. Being challenged or apprehended for shop theft was identified as one of the main triggers for violence and verbal abuse. Importantly, a store associate might not actively be trying to intervene in a theft incident but unintentionally be in the way of a criminal trying to escape. Some businesses have responded to growing levels of violent attacks against store associates with “no challenge” policies that are enforced with disciplinary procedures should an employee contravene them. Some associates that took part in this study were not supportive of blanket policies which they felt undermined their ability to assess potential risk and disempowered them. Furthermore, some reported that offenders would brazenly taunt them by openly stealing knowing that they were unable to respond.

There is a strong relationship between substance misuse, shop theft and the use of violence and aggression by drug-affected offenders. Offenders who are desperate not to be detained through fear of withdrawing from drugs can become volatile and threatening. It was estimated in the UK in 2018 that approximately 70% of shop theft was committed by frequent users of heroin, cocaine or crack cocaine.

Enforcing legislation

Another flashpoint for violence and aggression is upholding restricted sales on merchandise such as bladed articles, acids, alcohol and tobacco products. It has been estimated that more than 1 in 5 violent attacks on shop staff are triggered by age-restricted sales.9 There are also some voluntary codes applied by retailers to restrict the sale of some products. For example, some companies as part of their social responsibility mandate, have imposed a voluntary ban on the sale of “energy drinks” to under-16s. Customers wishing to purchase these products might also be asked to present proof of age documentation. It has been reported that the voluntary codes can create tensions between store associates and customers, particularly where there is no legal reason to deny the sale. Similar issues have also been raised in relation to the reduction in single use plastics in some countries. Customers using their own bags can provide an opportunity for theft.

Hate and ideologically motivated incidents (including armed active assailants)

Hate and ideologically motivated attacks can take two broad forms: ‘hate motivated incidents’ or ‘ideologically motivated attacks’ that seek to gain attention for a particular cause or in response to a specific incident.

Hate motivated incidents

Hate crimes are defined as ‘any criminal offence which is perceived by the victim or any other person, to be motivated by hostility or prejudice based on a personal characteristic. Although hate crimes are defined differently in different countries, some of the protected characteristics typically include race, religion, disability, sexual orientation and gender identity. Shop workers frequently experience challenging customers, but few incidents are as distressing and difficult to manage as personal attacks that aim to maximise hurt and humiliation – particularly when it occurs in a busy shop setting in front of customers and colleagues. This type of abuse can often take place over a prolonged period of time and can be particularly traumatic for victims.

Ideologically-motivated attacks and armed active assailants

Domestic terrorists and active assailants have targeted transit systems, schools, hospitals, as well as retail stores and/or shopping malls. They can be acting on a range of violent ideological motivations, including racial or ethnic hatred as well as anti–government attitudes. Active assailants might be motivated by a single issue (such as far right extremism) or a combination of ideological influences. In some instances, they might be acting in response to a personal incident of perceived humiliation, feelings of social exclusion and low social capital. Perpetrators might also develop their own distinctive justifications for violence that are difficult to categorise. The range of ideological influences and the idiosyncratic ways they manifest make these attacks difficult to predict. They can take on a variety of forms from lone actors and small groups of informally aligned individuals to networks who target violence toward specific communities.10 Although concentrated in the USA, these incidents also occur in other countries. For example, a 22-year-old gunman armed with a rifle killed three people and injured another four at a shopping mall in Copenhagen, Denmark in July 2022.

Robberies, ‘flash mob’ and ‘swarming’

The reality is that any business with cash or high value items on the premises can attract the attention of criminals. Robbers deliberately employ strategies of violence to force victims to hand over money, cigarettes, alcohol and other goods. Robberies can be particularly scary and intimating for store associates who might be physically hurt or threatened. Often demands are made of them that can be difficult to fulfil under duress, such as opening cash tills and safes or removing security tags.

Most robbers are armed with some form of weapon; knives, firearms, machetes, hammers and syringes are not uncommon. The most used weapon varies by country but it is typically a firearm or knife. Robberies are particularly volatile situations, particularly when offenders are under the influence of drugs or heavily intoxicated.

Due to a range of new security measures and situational crime prevention strategies that have become more sophisticated and widely available, armed robbery has changed significantly in the past two decades. Reflecting target displacement, armed robbers have turned their attentions to ‘softer targets’ as banks have installed sophisticated security that is too difficult for the average criminal to defeat. Convenience stores, service stations, liquor stores, and supermarkets (particularly those with pharmacies) are now experiencing more robberies.11 Participants also described concerns relating to multiple offender crimes such as ‘flash mob’ or ‘swarming’ robberies where a group of participants, often masked, enter a retail shop or convenience store en masse and steal goods. In these types of incidents, the number of individuals participating in the robbery and their apparent willingness to use violence can quickly overwhelm store associates and security guards. Aside from ad hoc media reports, there is very little reliable data to determine the prevalence of this crime type, but it was referred to in several interviews as an example of how offenders are becoming more brazen and aggressive.

Mental health issues

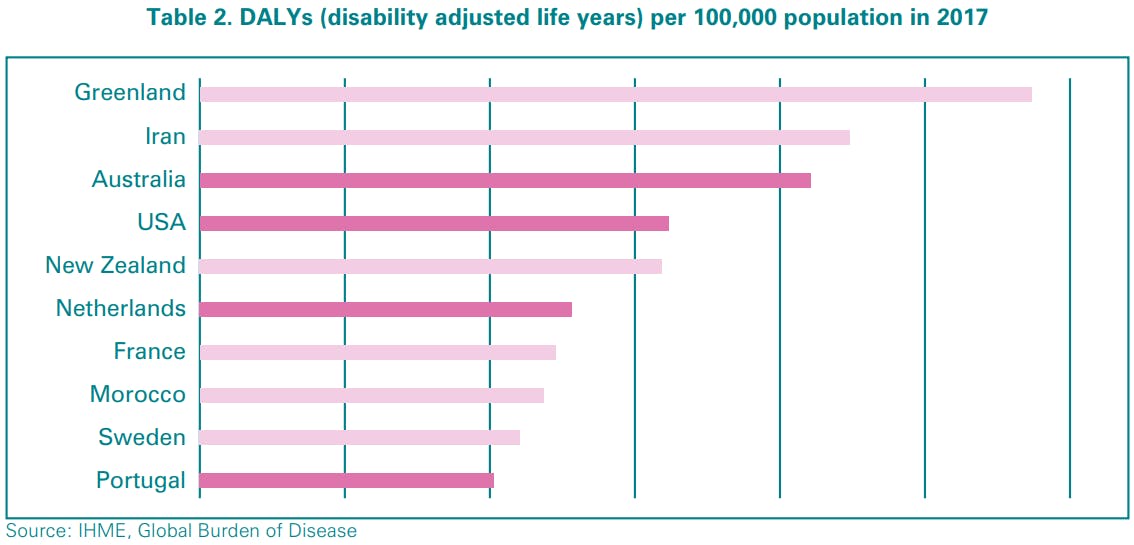

According to the Institute for Health Metrics (IHME) approximately 13% of the global population suffer from some kind of mental disorder. One way of measuring the prevalence of mental health issues in a population is to look at the disability adjusted life year (DALY) – a sum of all the years of healthy productive life lost to illness, be it through early death or through disability. As Table 2 illustrates, four of the countries that participated in the present study are in the most recent published top ten countries most burdened with mental illnesses.

This is not to suggest that those with mental health issues are more likely to offend, but it illustrates a range of societal issues that might impact upon a public-facing business. The data compiled by the IHME precedes the Covid-19 pandemic and the economic downturn experienced in many countries. These issues were highlighted by participants as further contributing to theft and violence in most at-risk stores.

During the COVID-19 crisis, shop workers experienced increased levels of violence and verbal abuse directed at them. As customers became agitated by restrictions, queues and limits on stock, some directed their frustrations at public-facing employees such as shop staff who were working hard to serve their communities.

COVID-19 triggered a lot of aggression in all countries, towards staff and between customers.

(Security Expert, multinational, Europe)

During COVID, there was an explosion in the number of aggressive incidents reported - 150% on top of the regular numbers. Why? Because not that many customers were allowed to visit the store, they had to wait in line outside and sometimes in the rain. And of course, they are disappointed, and they are faced with a lot of new regulations. Then they started arguing and fighting and sometimes spitting. The number of incidents reported before COVID was around, say, 15- 20,000 incidents a year. And in peak moments of COVID in the entire year of 2020, it was around 50,000 incidents: more than double.

(Security Manager, the Netherlands)

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a severe impact on the mental health and wellbeing of people around the world. At the same time access to mental health services has been severely impeded. Many retailers recognise that violent incidents triggered by the mental health impacts of the pandemic continue.

Pre-COVID we would average one new threat of violence per day. During the two big years of COVID that number went up 50%. We are now 50% higher in 2022 than what we were last year. I don’t know if COVID is the driver. There’s a correlation there but I don’t know if it’s causational. Mental wellness is by far and away the highest contributing factor. There is correlation to COVID, there is correlation to organised retail crime and, in the US, there is also correlation to having access to guns. They are all correlated factors that increase risk in our stores.

(VP Asset Protection and Safety, USA)

The impact of violence and aggression on employees

The impact and consequences of violence can result in life-changing injuries and even fatalities. The industry report, It’s Not Part of the Job, focused on capturing the everyday experiences of violence and abuse that store associates endured.13 It revealed frequent instances of employees suffering broken bones, being punched, kicked, stabbed with knives, lacerated with smashed bottles, and sustaining permanent sight loss through in-store assaults. Yet the impact of violence and verbal abuse stem far beyond physical impacts; violent encounters can result in long-lasting and life-changing emotional and mental health consequences for victims. Retailers in this study highlighted that it is not just a store associate’s physical health that can be impacted by aggressive behaviour, but often their mental health and psychological wellbeing.

Our first concern is our team member’s psychological safety. That’s number one by far. What we’ve noticed in these challenging markets is coming into broken windows and boarded up windows and graffiti and that kind of stuff. Or seeing the number of boosters and thefts, it takes a toll on them mentally where they see it every day.

(AP Senior Manager, USA)

For frontline employees, working in a grocery store presents an increasingly aggressive environment which can impact on their mental wellbeing. It is not surprising that The Retail Trust’s Health of Retail report (2022) found the rate at which retail workers want to leave the industry is consistently higher than for workers across other sectors.

External theft

In addition to concerns relating to violent assaults against employees, is the high volume of theft. This has reached a level so severe in some stores that shop workers describe it as ‘soul destroying’.15 The nature of retail theft is changing. It is no longer ‘just’ individuals stealing for personal use or to fund a drug habit. These offenders are still active, but they have been joined by professional criminal gangs who steal with the express intention of reselling stolen merchandise at scale (see textbox on Organised Retail Crime on page 7).

Industry research in the UK suggests that the majority of thefts committed against retail businesses (79%) are by repeat offenders that are not being sufficiently tackled by the police.

We know about 10% of our offenders are responsible for 66% of our ORC losses in stores.

(Loss Prevention Manager, multinational retailer, Australasia)

ORC theft is a major issue particularly in defunded states. There are no consequences in some states. The police stance is that if no one is injured then they are not coming. We have complete inability to combat ORC in those states, so we end up turning the criminals loose.

(Senior AP Manager, USA)

Although overall, the participants relayed that ‘grab and run’ continues to be the most frequent modus operandi for thieves, there are multiple techniques that are used by shoplifters. Three issues were repeatedly flagged as being of particular concern for retailers: theft via the self-service checkout, emergency exit ‘push outs’, and theft from customers.

Self-service checkout theft

Self-service theft continues to be a major source of theft in the grocery sector. A recent report published the ECR Retail Loss in 2022 found that survey respondents estimated that SCO systems accounted for as much as 23% of their total unknown store losses, with malicious losses representing 48%.17 Furthermore, two-thirds of respondents were of the view that the problem of SCO-related losses was becoming more of a problem in their businesses (66%). The present study found that some stores were rolling back the number of self-checkout stations due to high losses:

“ SCO systems accounted for as much as 23% of their total unknown store losses, with malicious losses representing 48%”

We started with self-checkout. We have over a hundred stores now with self-checkout. We stopped the rollout. We’re even rolling back some stores, so the self-checkout is taken out, normal cash registers are reapplied. The losses are just crazy. If you’re working on a normal cash register and somebody buys a bucket, you have to look inside it. Is it just one bucket, or is it filled? But at the self-checkout, people can just put everything inside and scan the bucket. We don’t have weight scales, but we are piloting the cameras to try and solve it. If not, self-checkout is “done”.

(Security Expert, Europe)

However, despite these huge losses, the dominant direction of travel found in the present study is towards more self-service provision with some grocers embracing a fully self-service model, particularly in their smaller format stores.

65% of all our transactions are finished at the self-checkout. We believe in the instrument of self-checkout; we want to go to 100%.

(Security Manager, the Netherlands)

As self-service provision evolves to include ‘scan and go’ and trolley checkouts alongside the more established model, the complexity of issues this presents for accidental losses and deliberate theft becomes more complex.

Emergency Exit ‘push outs’

A growing trend that several retailers identified as a concern in most-at-risk stores was the use of emergency exits for thieves to run from the store with stolen items. Thieves would either carry the stolen items or fill a shopping cart and then push that out of the emergency exit. An Assets Protection Senior Manager for a national retailer in the USA outlined the severity of the problem:

We had one store that had 56 fire exit push outs in one day and 153 in a week. Nobody wanted to come into work.

(Assets Protection Senior Manager, national retailer, USA)

Emergency exits are required by law to allow staff and customers to escape quickly and easily in an emergency such as a fire or an active assailant. Exit doors must not be locked or fastened in a way that they cannot be easily and immediately opened by any person in an emergency. This makes them a useful means of escape for criminals. Some retailers were responding by stationing a member of staff at emergency exits located near high value goods. This potentially offered some deterrence to the less brazen thief, but store associates reported that at this point most thieves had already committed to steal and would still run through the exit with the stolen goods.

Theft from customers while on the premises

Theft from customers was identified as a major concern for several retailers, particularly for retailers in Italy, Portugal and the USA. While this can and does occur in any location, in most-at-risk stores this was specified as a persistent problem.

Typically, thefts occurred in the parking lot. Security experts reported that offenders would often deploy a range of different distraction techniques. These included placing a shopping cart behind the customers vehicle so they would have to get out of the car at which point the offender would grab any valuable items within reach and tell the customer they had dropped something and then stealing from them when they diverted their gaze. Offenders also pickpocketed customers while they were in store, often taking advantage of handbags and valuable items being left in the shopping cart.

In terms of impact to the customers, the worst one is probably pickpocketing. Because these have an impact for the customer that is very bad, when it happens the customer holds us responsible for that, because it’s happening in our store.

(Security Manager, Italy)

Antisocial behaviour, homelessness, and loitering

Many retailers, particularly in high density areas, report issues with anti-social behaviour (ASB). This typically takes the form of groups of people congregating, committing criminal damage, graffitiing, or intimidating customers.

We have problems in terms of the type of people that are present in the area, that often are not so easy to manage. Like drunk people for example, we have some areas where they use our entrance to sit down and to drink, after they probably have stolen the wine from our stores.

(National Head of Safety and Security, multinational retailer, Portugal)

In addition, retailers report a growing problem with individuals who are homeless spending extended time in the immediate area outside their stores or stealing basic items for subsistence. In some locations, there might be a handful of homeless people who have identified a place to sit or sleep in alleyways, store entrances, or in the parking lot outside the store but in other locations, particularly in parts of the USA, large semi-permanent encampments have been established.18 This can present multiple problems for retailers – just some of the issues reported included littering, aggressive begging, obstructing entrances and exits, public urination and defecation, and signs of drug use.

Participants in this study were very sympathetic to the issues facing homeless people and want to see better service provision. However, they articulated frustrations with local governments to address the problem and voiced concern that the problem was only going to get worse post-pandemic and faced with economic downturn in many countries.

We’re seeing an incredible amount of homelessness and transient populations in a lot of these dense, urban areas. It’s making it difficult to run businesses in some of these locations. One of our stores has an entire homeless encampment right behind the store and the authorities are fine with it. They said they can have up to 50 tents there and when I say behind, I’m talking ten feet behind our store. So, as you can imagine, there’s a lot of drug abuse there. There’s a lot of things going on and what’s sad is that often times they’re not the violent people. From the stuff you see it’s mental illness, and drugs. So, that’s been a really challenging thing for us to figure out how to operate in that environment. (

AP Senior Manager, USA)

Summary

This section has outlined the main concerns that retailers are experiencing in their most-at-risk stores. While these factors are by no means unique to these stores, what sets the most-at-risk store apart from the rest of the estate is the sheer volume, severity, and frequency of criminal attacks against the store, its employees, and its customers.

By providing greater detail on the way in which risks are currently manifesting, it is hoped that businesses will be better equipped to recognise emerging issues in their own stores and respond swiftly. The following section outlines 7 key strategic principles that grocery retailers are deploying in their most-at-risk stores to tackle these threats and vulnerabilities. They represent the top-level strategies and approaches applied in the most-at-risk stores and locations. As mentioned above, some of these approaches might be very familiar in some locations, others might not be possible due to the legal context, but overall, as a framework, there were very few businesses that were actively adapting across all seven areas.

Keeping the most-at-risk stores trading: 7 key strategic principles

It’s not about immediacy but rather a strategy to stabilise and neutralise that environment over a period of time.

(VP of Assets Protection and Safety, USA)

This report focuses on the most-at-risk stores, i.e., those that occupy the highest level of concern for businesses. The previous section outlined the top-level concerns in these stores to paint a picture of the day-to-day problems encountered. Typically, a most-at-risk store will be characterised by frequent incidents of violence, verbal abuse, increased theft of merchandise (by volume and value), theft from customers, antisocial behaviour, and a range of social issues, such as homelessness and mental health, that present additional layers of operational risk and complexity.

Different terminology and scales are used to describe most-at-risk stores. Some companies had simple binaries of what they termed ‘basic stores’ (low risk) and ‘focused stores’ (high risk), whereas others had more disaggregated categories with up to a 10-point scale of risk. Furthermore, some companies were found to have separate registers for different types of risk e.g., for loss, food waste, or violence. Overall, most appeared to operate with – or be moving towards – a scale comprised of three or four risk ratings along the lines of ‘low risk’, ‘medium risk’, ‘high risk’ and some adding an additional category along the lines of ‘ultra-high risk’. There is a base level of security solutions that are common to most large grocery companies such as CCTV and electronic article surveillance (EAS); this section focuses on the cross-cutting principles that sit above the specific tactics.

It is important to remember that, at times, the strategy being pursued in these stores is at odds with the broader direction of the company and its brand. For example, putting products in locked cabinets that require a store associate to unlock them. There are difficult discussions taking place about how best to protect employees and assets while maintaining brand reputation and profitability. Although the tactics that sit within each of the 7 strategic principles might be different, the key point is about the extent to which the business is aware of risk, accepts the need to do things differently, aligns the different business functions, and enables specific actions to be taken.

- Awareness: To what extent is the business aware of the specific in-store risks and vulnerabilities?

- Acceptance: To what extent does the business accepts that the most-at-risk stores require special measures to manage the heighten risks?

- Alignment: To what extent has the business shifted practice to align with the security needs, particularly when this presents tensions with the overarching company brand and/or policy deployed elsewhere across the estate?

- Actions: To what extent is the business supporting and investing in concrete actions to mitigate risks?

1. DATA

Data is an important part of any risk strategy. After all, what gets measured gets managed. Some of the important uses of in-store incident data include:

- identifying new and emerging issues and risks

- identifying ‘travelling’ offenders operating at multiple locations across the estate

- signalling to offenders that their actions are noted, recorded and action is being taken

- reducing costs by ensuring that finite resources are targeted and efficient

- engaging with other businesses on shared concerns

- generating enhanced ‘buy in’ from law enforcement

- creating a risk model

- monitoring the impact and effectiveness of security solutions and strategies

- reassuring employees and allowing for successes to be celebrated

Despite the many ways that accurate data collection and analysis can help a business to manage risk, there was a lot of variation observed in this project. Although some businesses had a robust data collection and analysis process in place, these were the exception. It was acknowledged by several participants that internal data collection needs improvement; too many incidents go unreported due to the volume, a lack of staff time, and a lack of confidence that it will result in any action being taken by law enforcement and/or senior management.

There is a lot of potential to gather data so that we can gain more visibility of the issues. We can also analyse the impact of what we are doing.

(Chief Risk Officer, Finland)

Incidents are reported to a third-party provider and their analysts join the dots in the background. The more information they can feed in from retailers and the police, the more powerful it is.

(LP Manager, Australasia)

Retailers need to identify not only what their risks are, but also where they are most concentrated to enable the efficient targeting of resources.

Our critical shrinkage stores are not the same as our critical security stores. Sometimes you do have quite a lot of overlap, but sometimes you might have some really distinct stores that don’t have both issues, so our safety and security deployment principles are specific to the data. You might have a shop that has really bad anti-social behaviour and a really bad shoplifting problem, but it never suffers from a robbery. This informs which tools to roll out.

(Head of Security, UK)

It was clear from the interviews that accurate data was providing insights into cross-store prolific offenders. For organised or travelling offenders, having a team of investigators and analysts was revealing trends that otherwise would not have been picked up on. In these scenarios, businesses were centralising the security function to identify and respond to repeat prolific offenders.

Our resources to protect a store are exclusive to that store but organised retail crime (ORC) is agnostic to location. We have a special investigative team for ORC that is centrally managed out of the corporate office. They can work across multiple jurisdictions and are aware of how the laws vary state to state. So, for ORC we centralise the process.

(Head of AP and Safety, USA)

We’re typically quite tailored to stores or groups so we needed someone to centrally manage the offenders that work right across the UK. We knew we had offenders and gangs that would be popping up all over. So when they are identified as a prolific offender across different areas that case will go to the Crime Team who then work with the police to drive prosecution. They will go to the police and go ‘here’s 50 case files of this offender, go and prosecute them’. We’ve had some really great successes.

(Head of Security, UK)

Some companies are responding to the need for comprehensive data by making internal reporting more streamlined. For example, by introducing mobile devices and apps to enable instant reporting in situ. These can have multiple functions including the ability for mobile POS and communication through instant messaging to colleagues. Poor data collection severely limits the ability of businesses to conduct analysis that could help to bring awareness across the estate about new and emerging crimes. None of the above uses of data are possible without analysis – and this starts with accurate and timely incident reporting. There are certainly opportunities to mitigate risk being missed due to incomplete data recording. Businesses need to better support staff by providing them with the time, software and devices required to report crime.

Risk modelling

Participants described different methods for using the data collated to model the location, frequency and nature of risks. These can broadly be categorised into three main types based on the data they use:

Internal data only. Typically, this risk model would comprise of the number of incidents of customer theft, robberies, break-ins, vandalism, and aggression towards store associates.

Integrated internal model. A risk model devised and managed by an internal analyst that combines internal data (i.e., number of incidents) with externally available data such as police recorded crime, demographics and employment rate.

Integrated external model. A third-party designed and managed risk model that integrates storebased data with a range of other variables including socio-economic indicators, crime rates, the presence and concentration of crime generators (e.g., transport hubs, licensed premises) and potential crime inhibitors (e.g. police stations).

We are developing a sort of ranking, based on the number of events (e.g., stealing) that are recorded in the store due to the presence of our loss prevention specialists. We use the indicators to decide where to put more internal resource, such as loss prevention specialists, or to target external activities, such as pickpocketing.

(Security Manager, Italy)

We spend a lot of time understanding the environment we operate in and how to neutralise it to make it feel safe. We look at crimes against persons in the community that could show up within our buildings, so that could be threats of violence, shootings, stabbings, things of that nature. And also, crimes against property, but more retail-centred, so risk of theft, burglaries, robberies, any armed activities, etc. We use an external provider for that, and we throw some internal factors into it e.g., stability of the workforce.

(VP of Asset Protection and Safety, USA

We generate a store performance profile which uses about 100 metrics currently to establish a benchmark. We are still working through which indicators have historically been underutilised and which ones don’t actually tell us much. But we know that internal behaviours are important for helping loss prevention to deal with the issues. Relating it to theft there are definite accountabilities that ‘smart leaders’ deal with better so we look at the tenure of the leadership team. They help to mitigate circumstances that can lead to loss. Team experience is important; a lot of indicators come down to how engaged the store team is.

(LP Manager, Australasia)

We draw upon external factors such as the average wages in the area, the unemployment rate, stuff like that. And we make good use of internal factors such as stock losses. We register all types of incidents at store-level, and we collate that in the dashboard and use it to make a security plan for that store.

(Head of Security, the Netherlands)

Any risk model is only as good as the data that is entered into it. Related to the issue of under reporting above, participants in this study described concerns about the validity, reliability, and timeliness of data, both internal and external, that could skew risk registers. In addition, some felt that there was not enough understanding about which variables had the strongest explanatory or predictive power, how to effectively weight variables (i.e. weighting high-risk/low-frequency incidents such as armed robbery compared to low-risk/high-volume incidents such as theft), and how to control for variables such as store format (e.g. convenience, large format, petrol filling station shops, acquisitions/purpose built, etc.).

2. PEOPLE

During the fieldwork, one retailer told me that according to their risk modelling, they had a store that on account of multiple metrics, should have been one of their most-at-risk locations. Yet, it was one of their best performing stores. Investigating further, they found out that a local drug dealer’s mother was employed as a manager of the store and so it was largely considered to be ‘off limits’ for any criminal activity. Of course, not every high-risk store can employ relatives of the local criminals, but there is a bigger insight here and it’s about the power of people to protect a store, its assets, associates and customers.

Investing in and empowering employees

The previous section highlighted low staff morale and despondency across the retail sector. Associates need a reason to believe that they can win against thieves and aggressive customers. This includes investing in meaningful and bespoke training, so staff feel equipped to deal with criminal events and challenging issues, as well as providing them with equipment to enable them to quickly report incidents, communicate, and feel protected.

Companies are recognising the need for store associates to be in instant and ongoing communication with one another to quickly identify and respond to risk, particularly in locations where the volume of criminal activity is high, and events unfold quickly. Wireless headsets for store associates were observed in several stores. These were reported to have multiple benefits including improving colleague safety. Employees can communicate in real time to alert other staff members and security if a customer is becoming aggressive. In addition, they can discretely share information about suspicious behaviour or known criminals entering the store. The previous section highlighted low staff morale and despondency across the retail sector. Associates need a reason to believe that they can win against thieves and aggressive customers. This includes investing in meaningful and bespoke training, so staff feel equipped to deal with criminal events and challenging issues, as well as providing them with equipment to enable them to quickly report incidents, communicate, and feel protected.

The headsets take a bit of getting used to. You have to block out all the background chatter and learn when to tune in. But now I’ve got the hang of it they are very helpful. You feel like you are constantly supported, and you can ask someone to listen in and advise at any point.

(Self-service attendant, UK)

It’s great, I always feel connected even when I’m the only one on the shop floor.

(Cashier, UK on headsets)

Some companies are investing in body-worn cameras (BWC). One UK company has issued them to every public-facing member of staff (an investment of approximately 18,000 cameras nationally) whereas other companies have made a more modest investment and provide them only to specific roles e.g., the Store Manager. There is anecdotal evidence that BWC can provide reassurance to the store associate as well as deliver a perceived reduction in the volume and severity of violent incidents.

You can tell sometimes the customer will back off when they see that you’re recording them, but it doesn’t always make a difference. It depends on the situation.

(Store Associate, UK)

We’re a brand driven company, so we deliberately picked our 20 lowest risk stores to understand how colleagues would feel wearing them. So, it wasn’t let’s put it in the high-risk stores and start a media blow up. We went, ‘this is about how does it feel for our colleagues’, and that’s an easier reactive statement to have planned as well if people were going, ‘what the hell are you doing?’

(Head of Security, UK)

You need to think ‘what is it that a body camera is trying to do?’ We want it to prevent a verbal assault turning into a physical assault so it’s really about de-escalation. If you have a limited budget for safety tools, then you need to be quite specific about your deployment principles.

(Head of Security, UK)

Ensuring staff buy-in for body-worn cameras is crucial. There are some ways in which this was being achieved including communicating how footage is accessed, by whom and for what reasons. As one Store Manager explained:

All the recording is centralised, so it can’t be seen by people in store. So, for example, the Area Manager doesn’t have access to his or her team’s footage unless it’s specifically requested and approved.

(Store Manager, UK)

There remain several gaps in the knowledge base regarding body-worn cameras in the grocery sector, including who wears them; if they should be in constant operation or require activation; which models are most effective (e.g. outward facing screens, flashing light to indicate recording); and where on the store associate they should they be worn (e.g. lapel, chest). There is also a lack of robust evidence to identify exactly what the range of impacts are. Some companies are reluctant to use BWC for various reasons including the cost, potential customer disapproval, and legal concerns.

Enhanced employee training and upskilling

Training is an ongoing investment for companies requiring a skilled, knowledgeable, and motivated workforce. There were multiple ways in which store staff were trained to identify and respond to crime in store. This included off-the-shelf e-learning modules which could easily be repeated as a refresher, class-based modules, formalised certificates, and some companies were investing in a more in-depth learning exercises such as using theatre style delivery with role play to train staff. The topics were extensive, including theft, violence, active assailants, terrorism, and organised retail crime. Some security teams produced regular newsletters that would include updates on the latest trends in criminal activity, whereas other companies would send regular instant messaging updates with an overview of what was occurring across the estate nationally.

We do a significant amount of training on individual modules. We invest in de-escalation tactics with our leaders and with team members and active shooter training. It’s a worldwide issue but it is an epidemic in the US. Our training isn’t just e-learning, it’s a physical drill and everything else that associated with it in order to really change behaviour.

(VP Asset Protection and Safety, regional retailer, USA)

We have a special security training day that is held regularly. We cover violence issues, theft, and other crime situations. We focus on protecting yourself and handling threatening situations correctly. In addition to that day, we have different kinds of e-learning packages for personnel. We have made short 3-minute videos of every incident to show how to handle the situation.

(Chief Safety Officer, Finland)

Training for staff was an integral part of the loss prevention and security provision for all retailers. It was acknowledged by several participants that the training program had been impacted negatively by the COVID-19 pandemic in several ways. Firstly, there was high staff turnover as a result of the pandemic, and this has resulted in a less experienced and trained workforce. Secondly, much of the training provision was moved online. For incidents and scenarios that require interaction with a criminal or a rapid response, online delivery was not viewed positively.

Since Covid, a lot of the training has moved online and losing some of the context has been felt.

(Loss Prevention Manager, Australasia)

We used to have live trainings with actors in each store once or twice a year to handle aggression or robbery.

(Security Expert, Europe)

Customer service training was viewed explicitly as part of the loss prevention function for some retailers. If store associates were engaged and delivering operational excellence, the view is that theft and violence could also be managed.

The way we look at stock loss is different to how we have historically. The way we think about it now is about delivering operational excellence. So, if we’re filling merchandise gaps, we’re serving customers, we’re engaged, we’ve got the right stock rate then the outcome is that we’re also delivering on stock loss. If the team are engaged, then opportunistic theft will be less because the customers know that the team are on to them. They are defending the entry and exits and creating, from an offender’s perspective, a risk of getting caught. We can serve really well and have all the processes in place that make a great experience for the customers that want to come and purchase but this also creates a level of discomfort for the criminals as well.

(Development Manager: Loss Prevention, Australasia)

De-escalation training is also being used to train staff on how to identify and diffuse potentially aggressive altercations. Training is used for everyday aggressive incidents as well as more specific and rare scenarios such as armed robbery and active armed assailants. It is estimated that 85% of USA retailers have invested in an active shooter training program which typically adopts the ‘hide, run, fight’ approach.

We train colleagues to protect themselves and the immediate public, and then we’ll pick up the pieces after, even if that means letting someone steal. That training is there to preach ‘people, people, people’.

(Security Specialist, UK)

3. CONTROL

A step back from permanent closure is a concerted effort to exert heightened levels of control over every aspect of the store operation using a mix of technology, design, operational strategies, and people. Some businesses are undertaking an ‘operational reset’ which typically involve revisiting trading hours, changing merchandise assortment (including deleting high risk lines), removing some services, changing policies (e.g., on refunds) and (re)thinking about staffing. In some locations, it was the restrictions that were introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic that provided clear insight that the store could be managed differently with positive results.

During covid we were required to close overnight to do cleaning. There has not been an appetite to go back to it because we started to evaluate the number of criminal incidents that were happening overnight in our stores, what our shrink rates were, the number of apprehensions and other theft attempts overnight. And so, corporately we made the decision that we were not going to reopen those buildings for the foreseeable future. We saw that the customer was willing to shift their shopping pattern as no other retailers had overnight hours either.

(VP Asset Protection and Safety, USA)

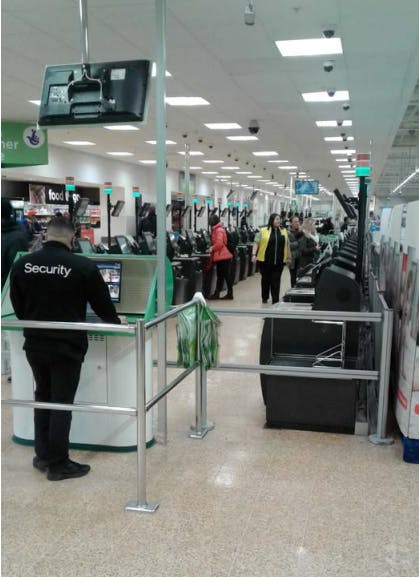

Some stores are moving away from ‘cathedral entrances’, 24/7 opening, and frictionless shopping towards an emphasis on enhanced control. The strategy is to intensify the control of customer movements in the aisles and throughout the store. This includes managing entrances and exits through the installation of one way automated and alarmed gates, creating physical barriers, using ‘bullpen’ and ‘store in store’ designs, restricting access to high-risk aisles, reducing or changing opening hours, or in the most extreme scenarios ceasing trading altogether either temporarily or permanently.

Controlling the flow of customers, particularly in the larger format stores, was viewed as an important part of a loss prevention strategy to deter thieves. Corralling is intensified in certain areas such as the selfservice checkouts to ensure that customers can’t bypass the payment kiosks. More generally, corralling was achieved through one way entrances and exits and supported with barriers and strategically placed shelving creating a ‘bullpen’.

We want to force customers to enter here, and then twenty feet over they exit. Hopefully that will reduce some shrink by forcing people to walk past the customer service centre or a staffed station, so they feel seen.

(AP Manager, USA)

For our alcohol departments we create “bullpens”, so one way in, one way out. That’s staffed with a register that encourages purchase of those goods in that particular area. In a handful of stores that do not have liquor bullpens, we have in-aisle gates that secure that aisle and prohibits shopping in line with state laws and any mischievous behaviour as well.

(VP Asset Protection and Safety, USA)

Once in the store, a range of strategies guide access to certain areas and merchandise. For example, gated aisles are being used to restrict access to ‘hot products’ such as alcohol, laundry detergent, and coffee. In some most-at-risk stores, the gates are locked and only opened during certain hours when there are more store associates on the premises (e.g. the laundry detergent aisle in one metro area was not opened until after 10am due to early morning ‘raids’ on replenished shelves). Other stores have notifications sent to store members using pagers or audible alerts when a customer enters the aisle.

Going one step further than gated aisles, some companies have adopted the ‘store within store’ concept for certain products such as perfume and alcohol in their most-at-risk stores. The areas have a dedicated POS, associate, and enhanced surveillance (as well as signage, PVMs, locked cabinets, etc.). Store policy typically requires that items selected in the controlled zone is paid for at a dedicated POS. Ongoing monitoring of transactions reveals if these items are being transacted at other tills – and by whom – to allow for reminders and additional training to be targeted to stores if necessary.

Turnstiles or gates that require a receipt or barcode to be scanned to exit are also being deployed in some most-at-risk stores, but this was not an approach favoured by all. Some interviewees commented that it would only potentially impact thieves who were planning to exit the store having not paid for any items – and that these determined criminals would simply find another route to exit the store (e.g. via non-staffed checkouts or ‘tailgating’). The receipt validation gates would not impact on customers who under-scan, deliberately or unintentionally, as they could still scan their receipt and exit.

We were thinking about receipt scanning and based on our opinion it doesn’t help. During rush hour, a customer will open it through the scanning of the barcode and then the second and third customers will exit at the same time. It might be effective for the self-scan walkaways, but not for the non-scanning of half of the items.

(Head of Security, Czechia)

It doesn’t stop you scanning five things and not scanning two of them; you still get a receipt and walk out.

(Head of Loss Prevention, UK)

It’s a bit of a joke really because you can steal 10 things and pay for one and you still have a receipt to validate your exit.

(Store Associate)

Most-at-risk stores were removing merchandise from the shelves, particularly in response to ‘steaming’, ‘flash mob’ and professional theft, and replacing it with dummy items, empty boxes or picture cards. The customer takes the box or card to a store associate who will retrieve the product from behind a counter or a locked room. In more extreme scenarios, several stores were taking the decision to no longer stock certain brands and products. Examples include printer cartridges, razor blades, designer apparel, and electric toothbrushes. The reason being was that not only was there ‘more products being stolen than sold’ but also these brands were attracting thieves to the store.

Sometimes in very extreme situations our knowledge of criminal activity can influence the merchandise assortment. So, operationally we will just choose not to carry that particular item in the store based on the level of risk. For example, within our alcohol categories we may not carry any of our higher end products that are more prolific or known for theft. On occasion we’ve provided that data to the merchant and they’ve in turn handed it over to the supplier. The supplier has offered some sort of recommendation in order to get their product in, that they’d be willing to concede on X, Y and Z or they would be willing to provide additional security features. I can’t say that we would always accept that or that we’d always deny it. It must be evaluated as to whether or not it makes sense for us to deploy those things – cosmetically and in terms of efficiency – or are we better off just not having the product altogether?

(VP Asset Protection and Safety, USA)

If some products only attract criminals to the store to steal, then we will remove that item in that location.

(Head of Security, UK)

In the most-at-risk stores, there is a trend towards using cabinets for a far higher proportion of everyday items regardless of unit price. For example, health and beauty care (HBC), washing detergent, air freshener and baby formula. In the most-at-risk stores, entire aisles of products are being placed behind locked cabinets. Reduced product accessibility can create friction for customers and undermine the in-store shopping experience. After the initial installation, some companies are looking at ways to reduce the friction, including staff-operated smartphones that permit any staff member to unlock product (rather than requiring a specific physical key) and customer-operated opening devices that require the input of a loyalty card or personal information.

There was a marked difference in opinion relating to the impact that locked cases and aisles has on sales. Some staff reported that sales had increased as a result (because the stock was actually available instead of having been stolen), whereas other interviewees were adamant that sales were negatively impacted due to customers deciding it was too inconvenient.

While it definitely reduces stock loss because they’ve got less colleagues on the shop floor than they’ve ever had before, they’re definitely losing sales from it as well.

(Security Manager, UK)

We have everything from essentials, detergent, bars of soap, locked up. We had a hypothesis that sales would decline a little bit, but shortage would drop drastically. Actually, the opposite happened. Sales went up and shortage dropped to almost nothing and so that told us that keeping that in place even if they were to drop out of our ultra-high stores isn’t actually hurting sales and so it’s a win-win.

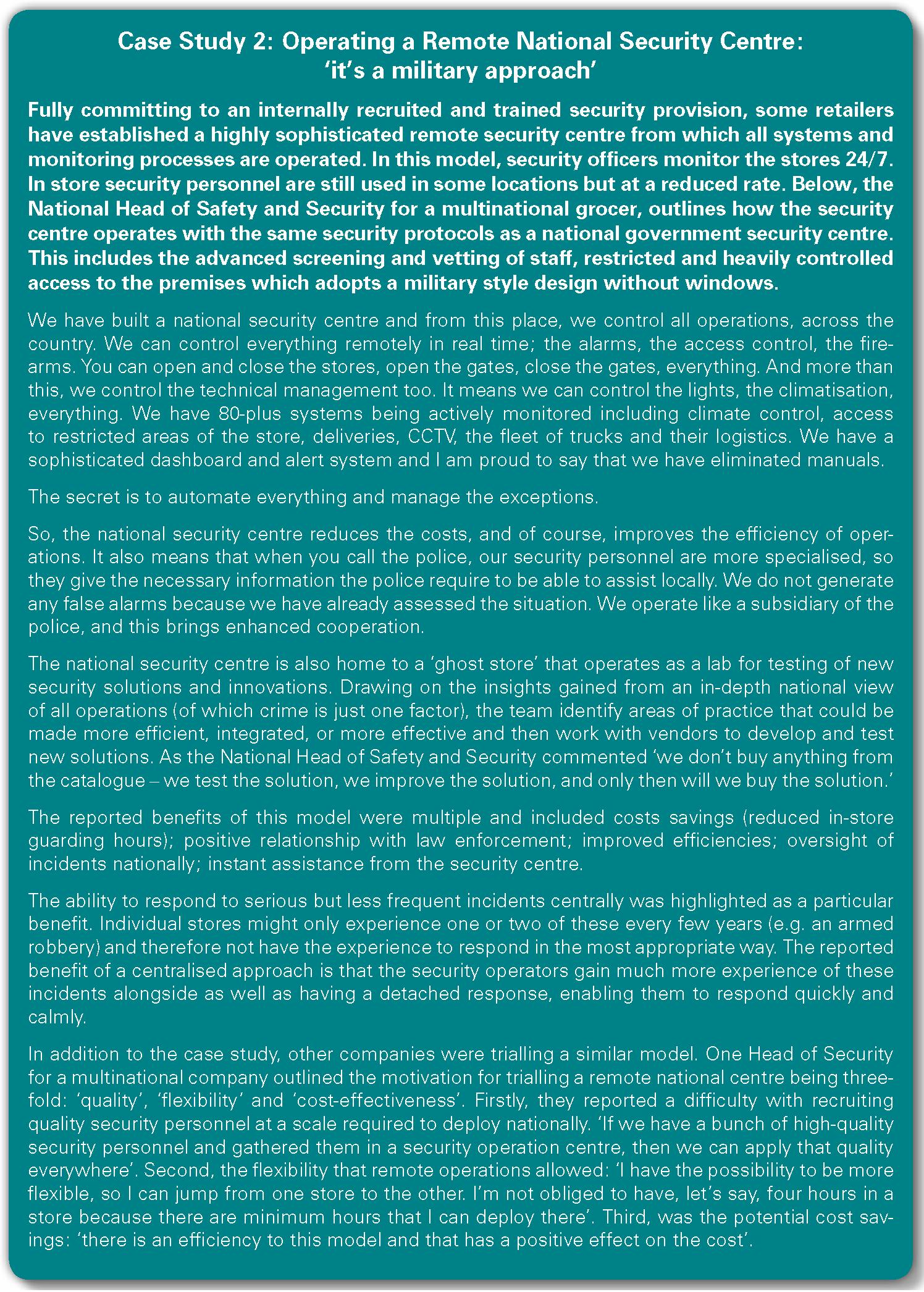

(AP Manager, USA)