Engaging Retail Buyers in Loss Prevention

Insights on buyers, and case studies on how to engage them to reduce losses

Table of Contents:

- Executive Summary

- Methodology

- Introduction

- How Buyers Impact Operational Execution

- Operationally Focused Buyers: The Impact of Corporate Culture

- Changing the buyer’s mindset: Education & Training

- Changing the buyer’s mindset: Enhanced Analytics

- Current Opportunity

- Summary of Key Findings

- Appendices:

- - List of Participating Companies

- - List of Survey Questions

- - Costco Case Study

- Appendix 4:

- - AutoZone Case Study

- - Best Buy Case Study

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

Languages :

This report, commissioned by RILA’s Asset Protection Leaders Council, is dedicated to identifying strategic initiatives that help retailers detect and prevent loss in their organization. Preventing loss is non‐trivial. It requires the cooperation of a variety of retail constituents including store leadership, distribution and transportation teams, product designers, and the legal department, just to name a few. Merchants, or retail buyers, are also an important part of the asset protection equation. This research identifies the various levers retail buyers have to influence retail loss and the obstacles asset protection groups face when seeking buyer engagement. Specifically, we determine which operational decisions require, or benefit from, buyer engagement.

Among RILA APLC retail members, we find substantial heterogeneity in the ability of asset protection teams to obtain the commitment and attention of retail merchants in spite of their importance to the protection of retail assets. Herein, we describe successful efforts undertaken by various RILA retail members to engage retail buyers. We identify what factors led to their success and, more importantly, offer a number of recommendations as to how to improve the coordination between asset protection teams and merchant groups. We generalize our findings by providing a framework retailers can use to benchmark their own organization. Specifically, we characterize what industry leading organizations are doing differently from ones that are moving towards such leadership and from ones who exhibit only basic competence in their asset protection approaches.

Overall, tremendous opportunity exists to improve merchant engagement in asset protection. Key findings include a narrow perception of asset protection’s role within the organization among buyers, a lack of understanding among buyers about their ability to impact loss, ineffective communication between merchant and asset protection teams, and a general lack of coordination among groups. These challenges are exacerbated by the fact that retail merchants are often managing multiple product categories and hundreds if not thousands of stock‐keeping‐units (SKUs). The complexity of the buying function results in buyers who are already overwhelmed with their existing initiatives.

Our objective is to provide asset protection teams with clear guidance on actions they can take within their organization to help ensure buyers are educated about their shrink prevention role and be able to cite a number of firms that have successfully motivated their buyers to think outside the traditional scope of their buying activities to deliver better results. In so doing, this research supports the central mission of RILA to have all its members work collectively – in a coordinated fashion – to facilitate growth through improved operational performance in the retail industry.

Executive Summary

This report, commissioned by RILA’s Asset Protection Leaders Council, is dedicated to identifying strategic initiatives that help retailers detect and prevent loss in their organization. Preventing loss is non‐trivial. It requires the cooperation of a variety of retail constituents including store leadership, distribution and transportation teams, product designers, and the legal department, just to name a few. Merchants, or retail buyers, are also an important part of the asset protection equation. This research identifies the various levers retail buyers have to influence retail loss and the obstacles asset protection groups face when seeking buyer engagement. Specifically, we determine which operational decisions require, or benefit from, buyer engagement.

Among RILA APLC retail members, we find substantial heterogeneity in the ability of asset protection teams to obtain the commitment and attention of retail merchants in spite of their importance to the protection of retail assets. Herein, we describe successful efforts undertaken by various RILA retail members to engage retail buyers. We identify what factors led to their success and, more importantly, offer a number of recommendations as to how to improve the coordination between asset protection teams and merchant groups. We generalize our findings by providing a framework retailers can use to benchmark their own organization. Specifically, we characterize what industry leading organizations are doing differently from ones that are moving towards such leadership and from ones who exhibit only basic competence in their asset protection approaches.

Overall, tremendous opportunity exists to improve merchant engagement in asset protection. Key findings include a narrow perception of asset protection’s role within the organization among buyers, a lack of understanding among buyers about their ability to impact loss, ineffective communication between merchant and asset protection teams, and a general lack of coordination among groups. These challenges are exacerbated by the fact that retail merchants are often managing multiple product categories and hundreds if not thousands of stock‐keeping‐units (SKUs). The complexity of the buying function results in buyers who are already overwhelmed with their existing initiatives.

Our objective is to provide asset protection teams with clear guidance on actions they can take within their organization to help ensure buyers are educated about their shrink prevention role and be able to cite a number of firms that have successfully motivated their buyers to think outside the traditional scope of their buying activities to deliver better results. In so doing, this research supports the central mission of RILA to have all its members work collectively – in a coordinated fashion – to facilitate growth through improved operational performance in the retail industry.

Methodology

This research entailed in‐depth interviews with one or more individuals representing 31 retailers that collectively account for over $1 trillion in US retail sales, or approximately 23% of all US retail sales. The focus of these interviews was to learn about asset protection strategies and the challenges asset protection groups face in engaging retail buyers within their organizations. Interviewees were asked to describe successful approaches as well as approaches that had failed to generate the desired results. Our primary objective was to develop a clear picture of the current role of buyers in asset protection and identify the decisions buyers make that influence loss through examples and case stories. See Appendix 1 for a list of participating organizations.

We also spent time on‐site visiting the asset protection teams, merchandising groups, store operations, inventory planners, distribution center managers, sourcing professionals, vendor representatives, and omnichannel strategists of six retailers. Through these interviews we captured first‐hand information about how other parts of the organization perceive asset protection. We utilized the output of these site visits to ultimately design a survey that we distributed to 336 buyers among select RILA APLC retailers. The survey helped us identify what shrink prevention activities buyers currently assist with and what more can be done. More importantly, it captured the buyer’s perception of asset protection activities such as the asset protection team’s ability to communicate, to provide analytical solutions, to influence decision‐making, and to improve retail performance. See Appendix 2 for a list of survey questions.

Introduction

Retailers have long been concerned with the level of inventory loss, often termed inventory shrink, in their stores and supply chains. Our existing measure of shrink – a measure that identifies the aggregate dollar value discrepancy1 between actual and expected inventory – is commonly assumed to be approximately 2% when reported as a percent of sales. Today, the term inventory shrink is synonymous with inventory theft – or stock loss2 . Thus, retailers commonly seek to prevent inventory shrink through the adoption of theft prevention techniques within the store, techniques that include video surveillance, putting products behind glass or devising special tags for specific merchandise, and investing in alarms at store entry and exit ways.

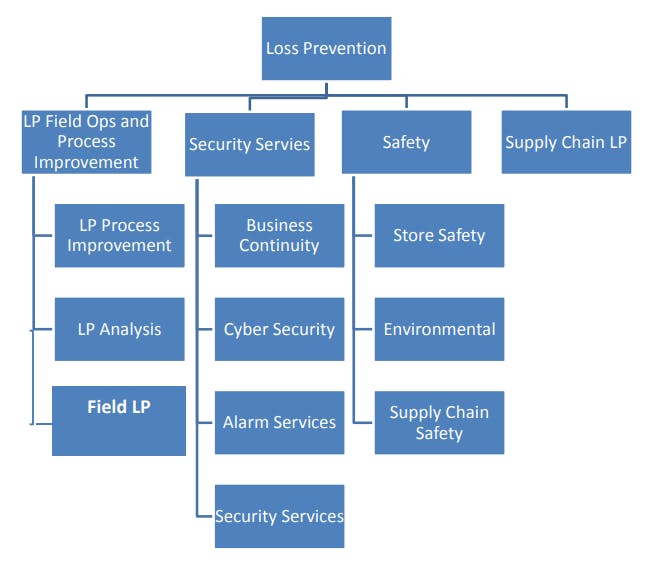

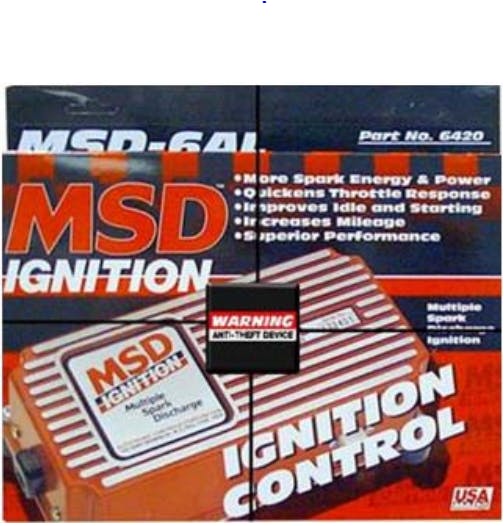

This focus on the theft prevention has, in some organizations, led to the perception that asset protection teams are also sales prevention teams as many of the theft preventing techniques make it difficult for the consumer to shop the store or experience the product. Traditionally, asset protection teams have been associated with stopping the thief whether that thief is a customer, vendor, or store employee. Not surprisingly, we found only 32% of the buyers surveyed viewed the asset protection team as a partner in efforts to drive sales. In other words, the vast majority of buyers surveyed perceive the asset protection team to be an obstacle to retail sales performance. Figures 1 and 2 highlight this concern. Figure 1 shows the challenge that traditional solutions to asset protection cause for merchants who care about sales and quality shelf displays. In this example, the consumer is unable to identify the product let alone read any of its specifications. Figure 2 shows how the use of locked cases to deter theft may detract from the display of product and thus negatively impact the consumer experience. Moreover, a retailer requires flawless execution in order to respond to a customer service request button in the allotted time. Without easy access to the merchandise, consumers may abandon their purchase imposing both the cost of lost sales and lost goodwill on the firm.

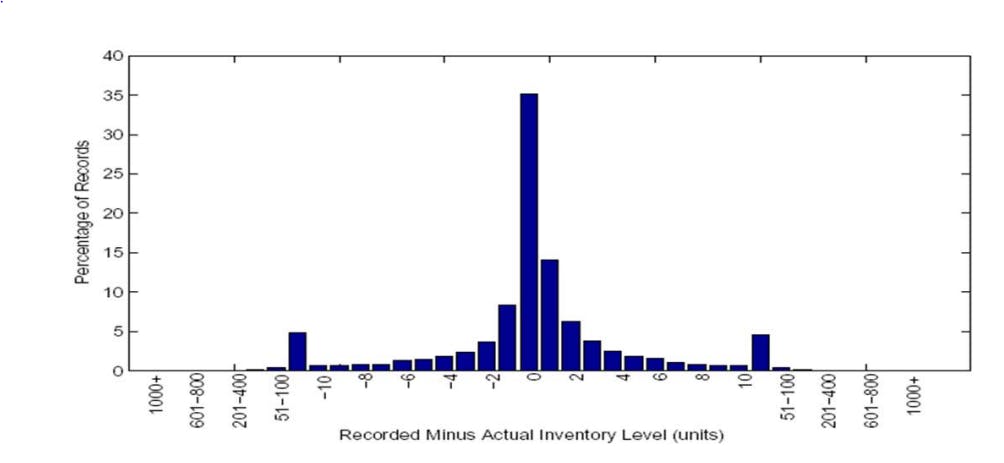

With this research, we want to offer an alternative perspective, namely, a perspective in which shrink is viewed not merely as the result of inventory theft but rather the accumulation of daily process errors within the retail store and its supply chain. These process errors result in inventory discrepancies. At times, these errors can result in more inventory on the shelf than expected (a positive discrepancy) and, at other times, these errors (including theft) can result in less inventory on the shelf than expected (a negative discrepancy). Positive discrepancies result in the retailer carrying inventory they may not actually need and the costs associated with such inventory whereas negative discrepancies may lead to product availability problems that impact the consumer’s purchase experience generating lost sales and eroded customer loyalty. See Figure 3 for a histogram of positive and negative discrepancies at a particular retailer where only 35% of the inventory records observed were accurate (e.g., where the quantity on‐hand in the store matched the quantity this retailer believed to be on‐hand in the store based on the computerized inventory records).

Figure 1: Traditional Approaches: Shrink & Sales Prevention.

Figure 2: Traditional Approaches: Requiring Consistent Execution.

Figure 3: Distribution of Discrepancies

Note: If discrepancies were generated entirely by the theft of inventory, one would expect fewer units on the shelf than in the record resulting in a histogram that was skewed. Instead, we observe that discrepancies are nearly equally likely in the positive and the negative direction.

Unlike the term shrink which is analogous to theft and specific theft solutions, this broader definition of shrink – inventory discrepancies that arise from poor operational execution ‐ can be a more effective way to engage buyers and others organizations within the retail chain. This broader definition can be tied directly to measures that matter to buyers such as sales and product availability and may enhance their willingness to collaborate on asset protection efforts. The prevention and correction of process errors requires a collaborative solution within the retail organization and across firm boundaries. Asset protection experts need to better understand how such process errors arise and help educate other members of the retail organization, including buyers, how their actions ultimately influence the likelihood of such errors occurring.

In the sections that follow, we describe the complexity of the buying function, illustrate how buyers are rewarded for their performance, and highlight how merchants can influence the operational performance of retail organizations.

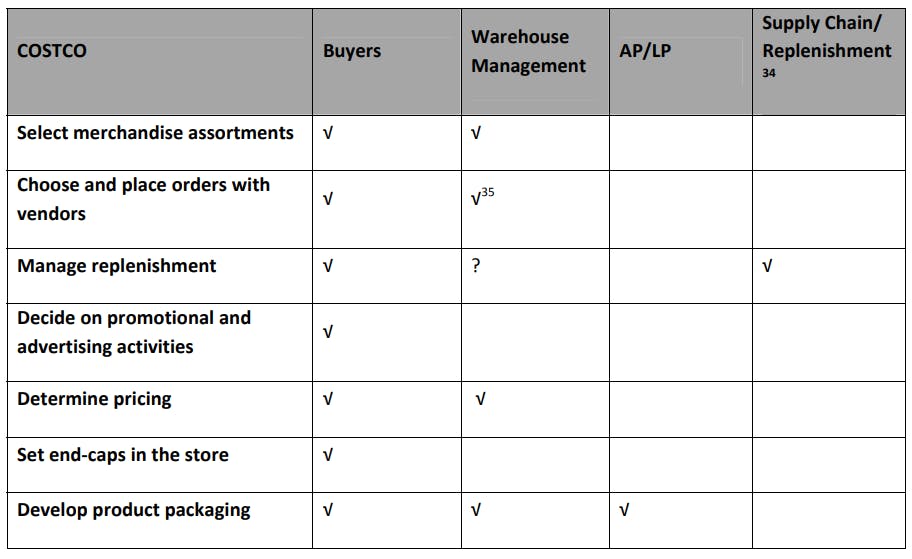

How Buyers Impact Operational Execution

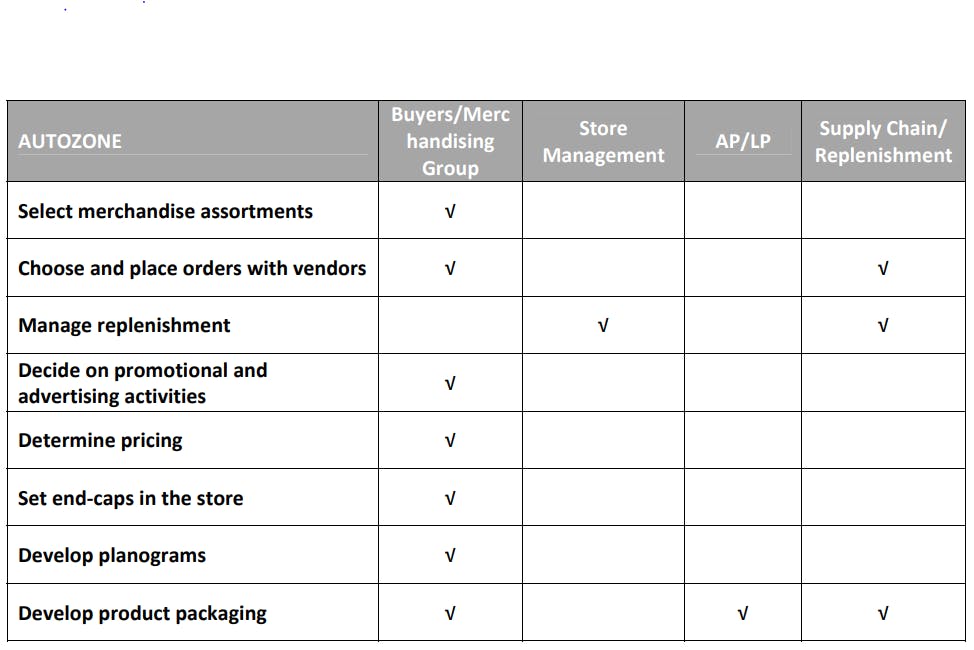

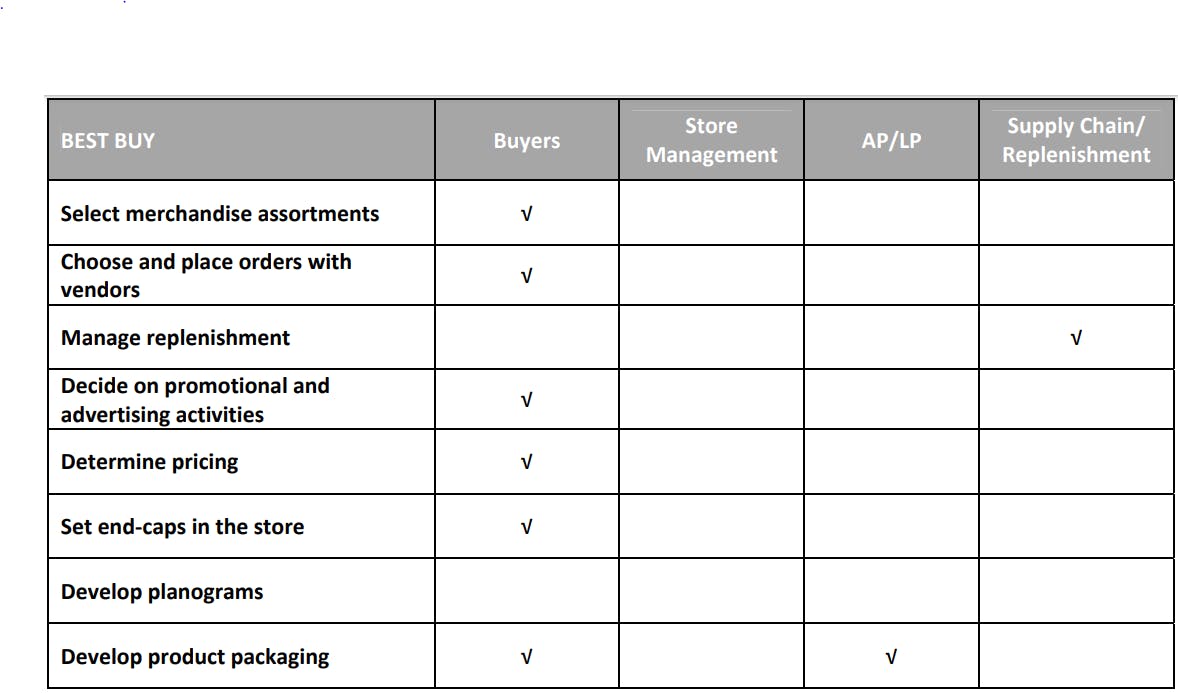

Retail buyers are often described as the “CEO” of their product category. Historically, merchants negotiated with vendors, established prices, determined order quantities and replenishment frequency, designed the planogram and shelf displays, and more. More recently, as the role has become more complex due to the proliferation of SKUs and vendors, many of the sourcing, inventory planning (ordering and replenishment) have been delegated to other organizations within the retail firm. While the retail buyer will advise other groups on their preferences and share their category strategy among all team members, the buyer will possess decision rights primarily over product selection (including whether to utilize branded or private label items), packaging, new item set‐up, planogram design, pricing, promotions, and markdowns, and the overall assortment (see Figure 4)3 .

Figure 4: Merchant Decision Rights.

As product category CEOs, these buyers face an enormous challenge. The complexity of their job is, to some extent, overwhelming especially in product categories that are particularly competitive. The workload buyers face depends on the number of vendor relationships they are managing, the number of SKUs they oversee, the number of line reviews they conduct per year, the frequency of new product entries, the occurrence of planned promotions, the financial importance of their product category, and more.

Among the buyers we surveyed, the majority of them (43%) managed two to five product categories representing 6% of the firm’s business. A typical buyer in our survey managed 13,000 SKUs and 34 different vendor relationships. Not surprisingly, our interviews revealed that buyers are essentially pushed to their limit in just trying to fulfill the requirements of their existing role.

Buyers tend to be focused on the retail consumer. When asked to identify the primary drivers of customer dissatisfaction, 80% of the respondents listed “out‐of‐stocks” as one of the leading sources of dissatisfaction followed closely behind by product price and selection. However, our interviews revealed that few perceived asset protection as having a role in the prevention of out‐of‐stocks. Instead, buyers tended to point to forecasting, replenishment, and poor store execution (merchandising, employee assistance, etc.) as the main drivers of out of stocks. An opportunity exists among asset protection leaders to make the link between out of stocks and asset protection activities explicit across the retail organization.

When asked whether asset protection was a factor they regularly took into account, few (less than 10% of those surveyed) identified it as a key driver for their category performance. The categories where asset protection was mentioned repeatedly included electronics, cosmetics, and fashion accessories. Most other buyers considered asset protection to be an activity delegated to other parts of their organization over which they had little control or influence.

Our interviews with asset protection teams, however, revealed that buyers can play an important and substantive role in helping to prevent stock loss. Buyers can influence shrink prevention in the following key ways:

- Manage Vendor Relationships. Buyers are the key people who interact with vendors. Therefore, if the asset protection team wants to do something differently (e.g., packaging) the buyer needs to be involved. Moreover, the buyers, due to their relationships with vendors, are often the first to hear of industry‐wide problems within a particular product category or with a particular item that might be important for asset protection teams to know.

- Product Selection. Buyers, when selecting product, can help Identify product that may need additional security tags, keepers, locked pegs, spider wrap, etc. 4 Buyers can work with vendors to ensure some of these tagging options are executed prior to delivery. Alternatively, buyers can work with stores teams to set up empty boxes, tear pads, or display product dummies.

- Merchandising Decisions. Buyers can limit presentation quantities, offer testers, and determine product placement on the floor. Moreover, buyers determine the assortment and select items to minimize the likelihood of discrepancies.

- New Product Introduction & Resets. The buying team is responsible for the integrity of the process and data used for new product introductions and resets. The accuracy of this process has been directly tied to the prevention of stock loss. For instance, accurate product setup and resets lead to correct tracking of costs, price, out‐dates as well as correct unit of measures that yields system inventory accuracy. It also ensures that the signage and promotional materials seen by consumers accurately reflects the strategy of the product category.

- Determine Product Flow. Buyers often make the decision about how the product flows through the supply chain (e.g., direct store delivery, full case pack shipment, break pack shipment, etc.). This impacts the complexity of the supply chain and ultimately the likelihood for mistakes and ultimately loss.

Buyers, on the other hand, did not recognize that so many of their decisions ultimately impact the quality of operational execution throughout the retail supply chain. Most, 53%, of the buyers surveyed pointed to organizational silos as a key barrier to improving collaboration between merchandising and asset protection. These same silos prevent buyers from understanding their larger role in the organization beyond knowing the retail customer preferences and making appropriate product selections to match those preferences and grow their category.

Operationally Focused Buyers: The Impact of Corporate Culture

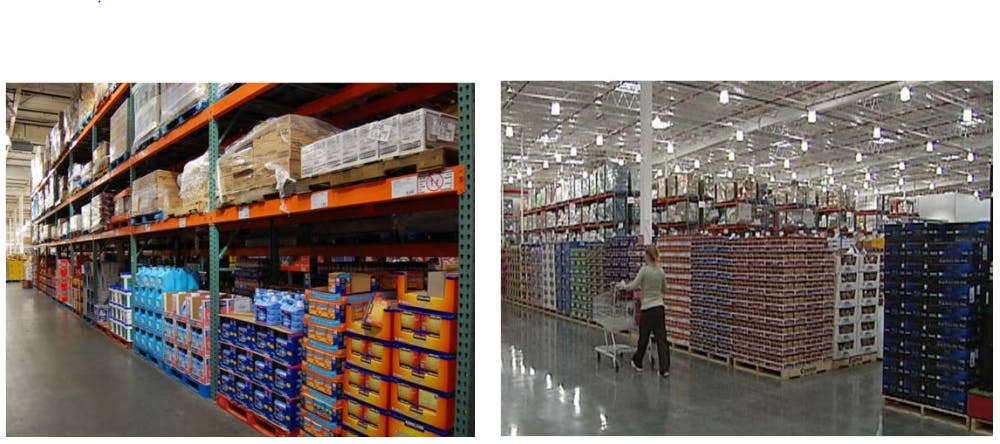

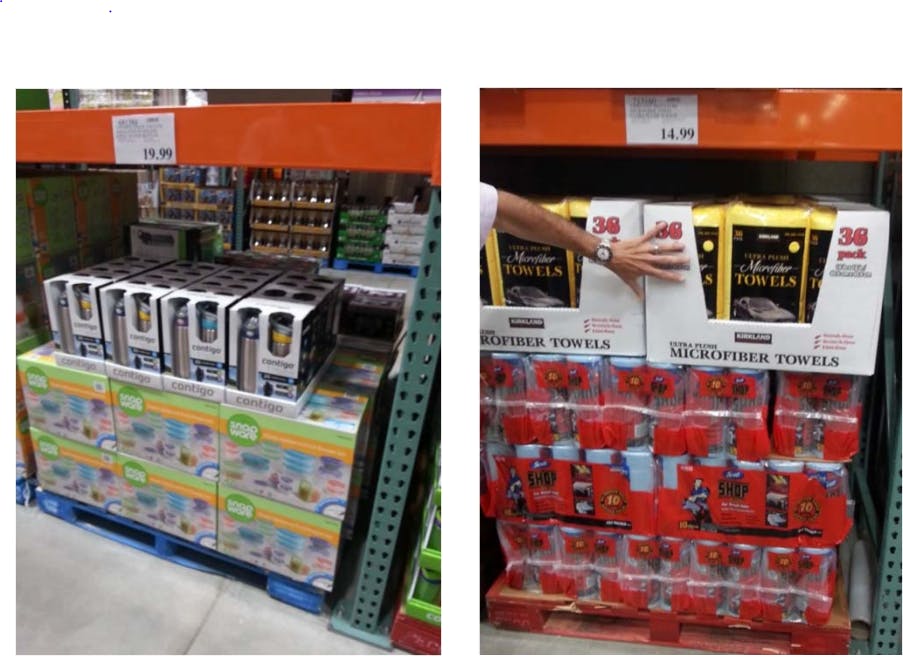

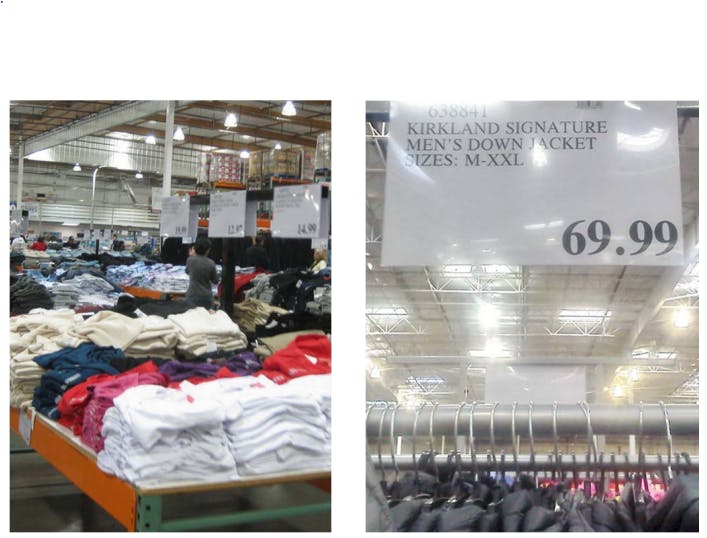

One retailer stood out among the rest in that their buyers, without prodding, identified asset protection as a key element to their performance during interviews. Buyers at this retailer, Costco, faced planogram pressures in that their category performance relied on the productivity of the space they were allocated within the warehouse (see Appendix 3 for the full Costco case study). Even buyers among retailers whose margin measure included shrink did not identify asset protection as an activity that was important to their business as often as those Costco buyers.

What we found differed at Costco relative to other retailers was a culture that valued operational excellence. For instance, buyers consistently take into account the operational costs incurred by warehouses in the form of labor. They work with vendors to deliver floor‐ready product to warehouses. This avoids the need for warehouse employees to receive a pallet, unpack it, and shelve individual items – a process which requires substantial time and labor. Moreover, by having 95% of their goods sold on pallets, Costco avoids additional handling that may increase the likelihood of damages, misplacement, or loss.

However, it goes beyond the decision to merchandise product on pallets, a decision not appropriate for many retailers. Costco buyers think hard about the negative impact variety has on operational execution and ultimately on asset protection. Specifically, to avoid confusion among their members and their employees, they avoid having product in two different locations and they minimize variety within product categories. They also work closely with their vendors to ensure they understand what it takes in terms of product design and packaging design to minimize returns, damages, and other forms of stock loss.

In addition, merchants think carefully about the workload required for warehouses to execute their plans. One example of this is how the merchants elected to move away from seasonal resets that required the majority of new merchandise to enter the warehouse at the same time at the start of a season. They replaced this with planned resets that differ in timing across product categories. In so doing, they not only keep the inventory fresh and exciting but also balance the workload required at the warehouse.

This focus on operational excellence is driven in part by their incentives. Specifically, buyers are allocated space based on productivity targets. Buyers must meet a minimum threshold of sales per week per warehouse per item in order to keep a select product in the assortment. Any stock loss due to damages, theft, or other factors means lower space productivity. As a result, buyers are very selective about what they put on the warehouse floor. Moreover, Costco tracks not just the price buyers pay for an item but the net landed cost of getting that item into the hands of their members. Buyers therefore have an incentive to insure the shipment flows efficiently through the supply chain. In other words, they work closely with vendors to prevent items from needing rework upon arrival at the distribution center or warehouse, to verify the packaging prevents stock loss and damages, and to make sure both pallets and product displays are easy to handle within their distribution network and warehouses.

Moreover, Costco buyers possess a deep understanding of retail built over years of experience in the same role. While the majority of the retail buyers surveyed (57%) had been in a buying role for 10 years or less, Costco buyers had substantially more experience in their positions. Moreover, we learned that buyers at most retailers move roles every two years creating a churn in the buying functions that impedes operational improvement.

While the Costco incentive design and culture help generate a strong commitment to asset protection among buyers, another factor we found important among Costco and other retailers is the amount of store experience buyers had prior to joining the merchant group. Buyers who had in‐store experience were more likely to take into account store operations and asset protection challenges in their buying and merchandising decisions.

Changing the buyer’s mindset: Education & Training

It is unlikely that the asset protection teams will be able to immediately change the culture of the organization or singlehandedly alter the incentives faced by buyers or replicate the Costco business model. Should these asset protection groups therefore forgo trying to change the mindset of the buyer? The majority of retailers we studied don’t believe so. Our interviews revealed that there are several key paths to success in trying to change the mindset of the buyer. These include (a) buyer education and training and (b) enhanced analytics. We discuss each in turn.

What emerged clearly in our interviews was the need for buyers to better understand the flow of product in the supply chain and all the touches associated with the movement of goods from vendors to the end consumer. Many buyers saw their role as understanding the consumer’s desires (e.g., product colors, fabrics, etc.) and the type of assortment needed within a particular category to meet those consumer preferences.

The same is true with retail execution and merchandise buying. In order to effectively protect the assets of the retail organization, merchants and asset protection teams need to collaborate. Asset protection teams should promote a design for execution mindset. This means that they should educate buyers about how their choice of variety, their planogram design, and their packaging features can help or hinder asset protection.

The objective should be to help merchants think about how they design their category to prevent loss. This includes far more than source tagging. It means thinking about how variety may impede sales. Marketing research has shown that too much variety can actually cause shoppers confusion at the point of purchase and consumers may actually select no choice than endure having to choose amongst too many variants6 . Too much variety has implications for operational execution as well. Store employees, warehouse employees, and others tasked with the management of inventory can also become confused in stocking, counting, or selecting merchandise.

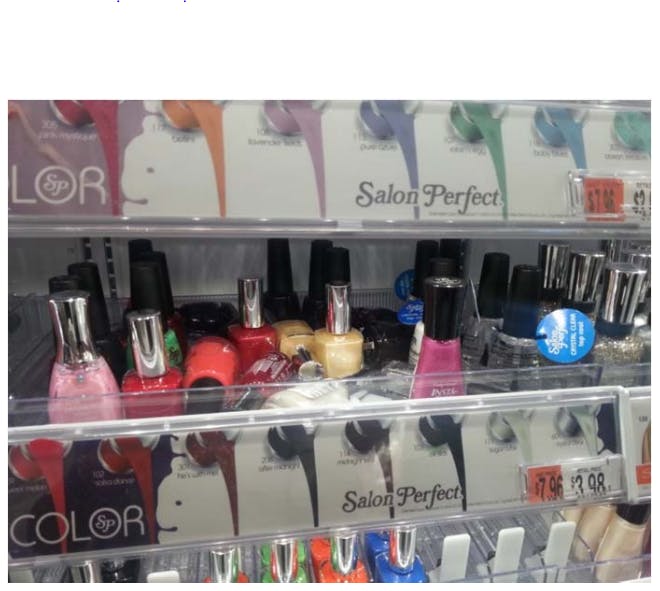

Take, for example, the picture below (Figure 5). This is inventory that has been brought from the backroom of this retailer to the store floor in order to replenish shelves within the cosmetic category, a category that is notoriously challenging for asset protection leaders. It is very clear that the extent of variety (e.g., different colored lipstick) and lack of clear differentiating markings or packaging will make the process of stocking the shelves not only time consuming but error ridden as employees attempt to identify the product and locate the right place to shelve it.

Figure 5: Product Variety and Operational Execution.

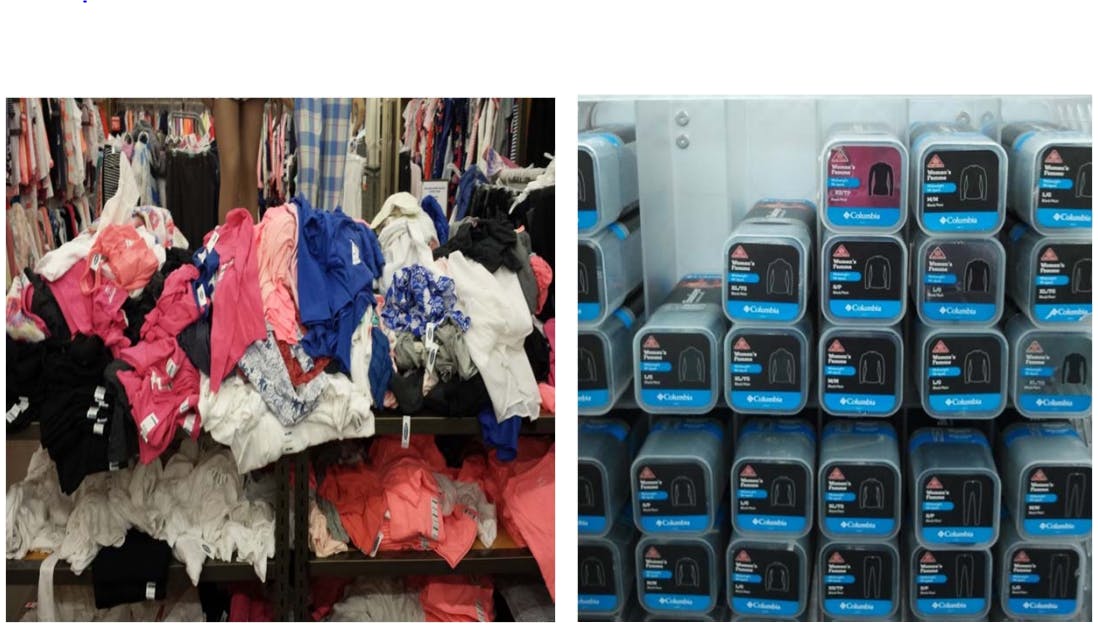

Research shows that lowering the level of product variety can result in lower levels of stock discrepancy however few buyers are aware of this link. Moreover, offering packaging design that is more distinctive and easier for both consumers and employees to manage (e.g., differentiate one close variant from another) can also improve operational execution and prevent stock loss. Figure 6a compares apparel items that are merchandized on a shelf where consumers have to go through items one‐by‐one to find the desired color and size to items merchandized on a shelf where the color and size are clearly delineated for both the consumer and those needing to restock store shelves. The store displayed on the right side of Figure 6a is clearly facing a number of operational challenges. Store teams and buying teams alike would be appalled with the presentation of that category. But, how often does one consider that packaging innovation might be able to assist with store execution and prevent such merchandising disasters. Figure 6b presents a more traditional arena for packaging innovation. Here we see the stark difference that adding color to packaging can make in helping to differentiate among product variants. The top panel shows a single brand – but multiple variants ‐ of deodorants. The bottom panel shows a single brand of deodorants where each of the variants within the brand are easy to distinguish. This clear demarcation helps the customer find what they are seeking to purchase more quickly and helps store operators accurately and efficiently maintain store shelves.

Moreover, without improvement in packaging design, even offering consumers tear pads whereby they bring a description of the item to the front for purchase can lead to troublesome errors. Take, for example Figure 7. This item was locked in a special storage area near the store manager’s office. Consumers were instructed to bring the tear pad to the cashier who would then enlist the help of a store runner to select the item and bring it to the customers. The trouble was that there were two different SKUs for this tear pad. One item was the high end item that retailed for $1,200. The other was a lower end item that retailed for $800. Can you clearly and quickly differentiate between those two items given this packaging below? Needless to say, selection errors occurred frequently such that a customer paying for the low end variant left the store with the high end alternative.

Figure 6a: Packaging Aiding Store Merchandizing

Figure 6b: Packaging Differentiation

Figure 7: Product Identification

Finally, asset protection leaders can help merchants understand how their choice of fixtures can also impede operational execution. Take, for example, Figure 8. Store operations shared with us how challenging this fixture was to maintain, stock accurately, and for the customer to shop. The result was high levels of product loss for these items.

Figure 8: Store Fixtures and Operational Execution.

Awareness of these issues can be part of a broader educational process among merchants. The key message is two‐fold: (a) asset protection issues go beyond simple theft prevention and extend into operational execution and (b) buyers, and the decisions they make, are critical to effective operational execution.

This educational process will not be easy. Of the retail buyers surveyed, 88% of them were unaware of any asset protection training being held within the buying organization. The remaining 12% who reported that training existed noted that it was infrequent (e.g., less than once per year). Given the two year turnover in the buying function, many buyers will have never been educated about their potential role as part of the asset protection solution. Moreover, this lack of longevity among buyers means the asset protection teams continually have to build new relationships with new buyers and explain why they should care.

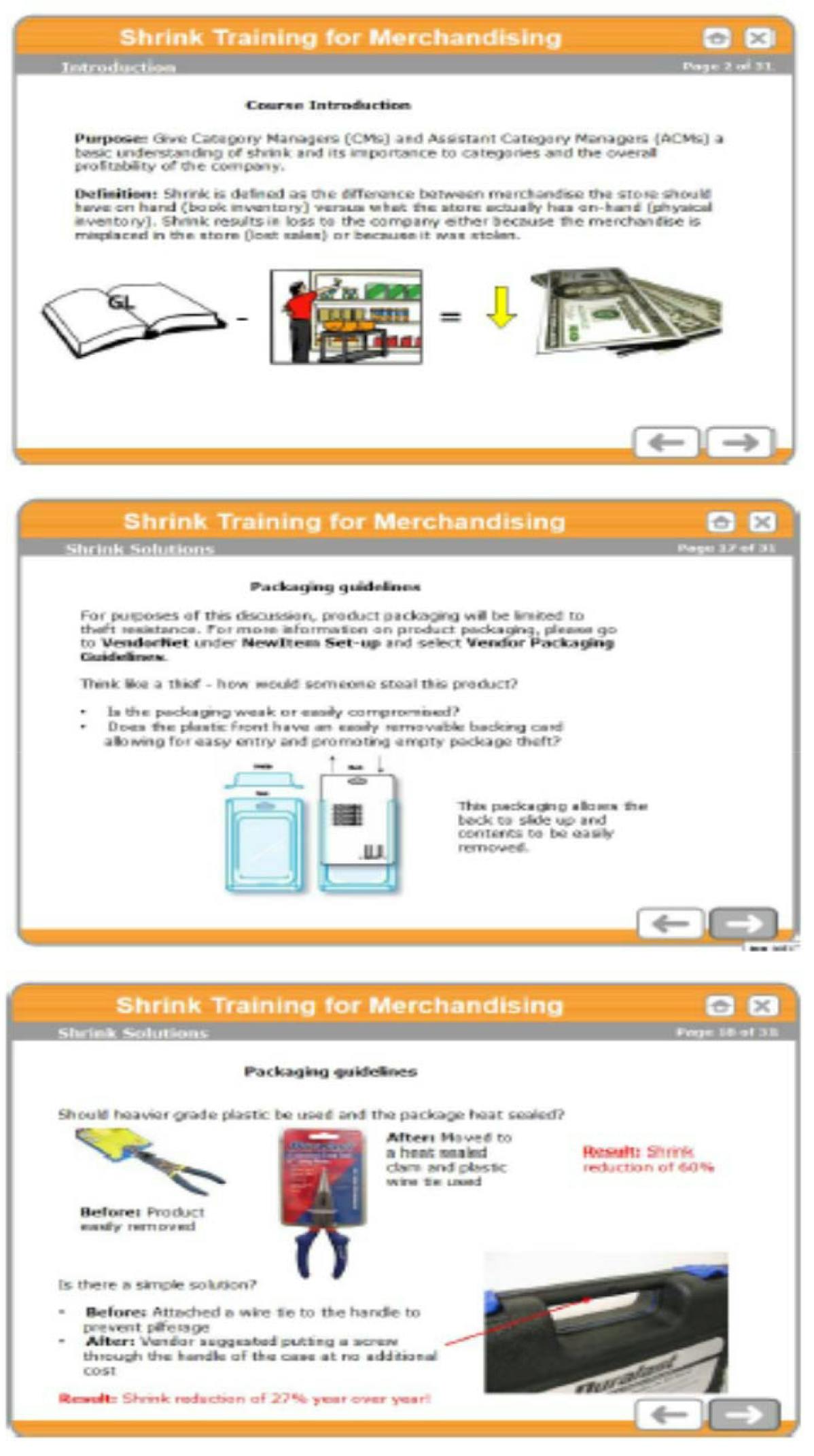

This need for perpetual re‐education suggests that retailers require a more efficient way of distributing knowledge to buyers about their impact on operational execution. One big‐box retailer we interviewed had developed on‐line training tools that could be circulated among buying teams and through a great deal of effort managed to get their training program incorporated into the buyer’s onboarding process. Part of their success was due to the asset protection team’s use of broader terminology. Rather than describing their role as merely controlling shrink, they framed the discussion in terms of protecting the profit of the firm.

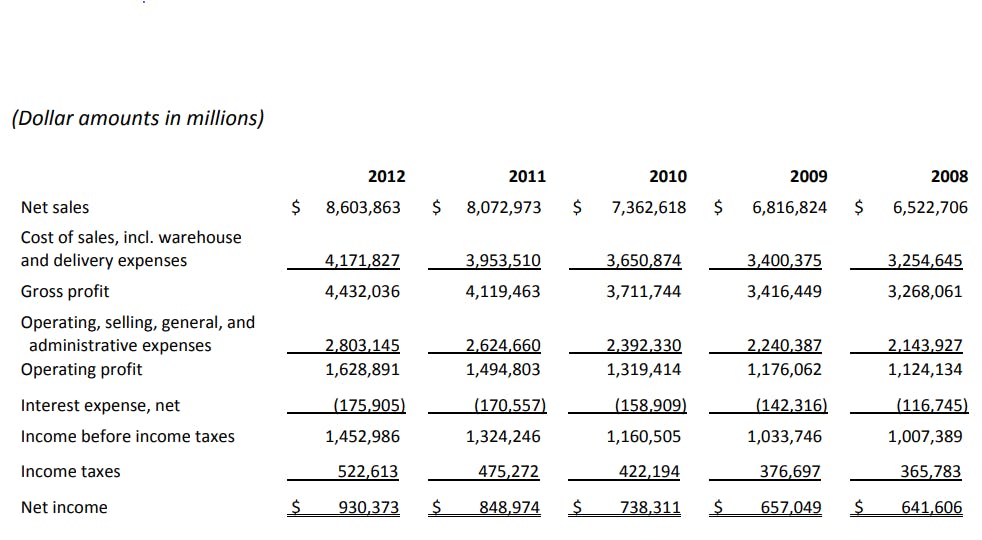

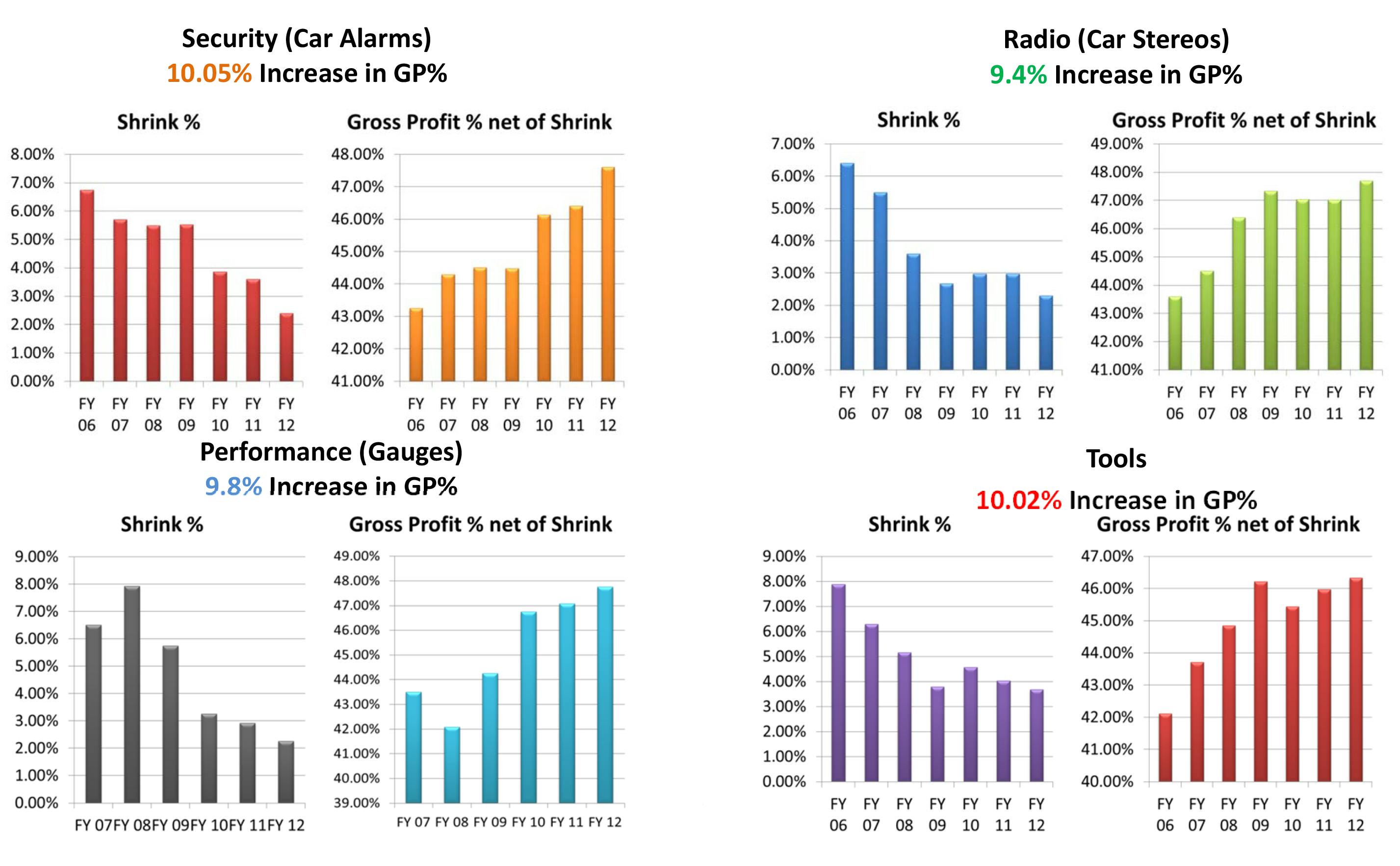

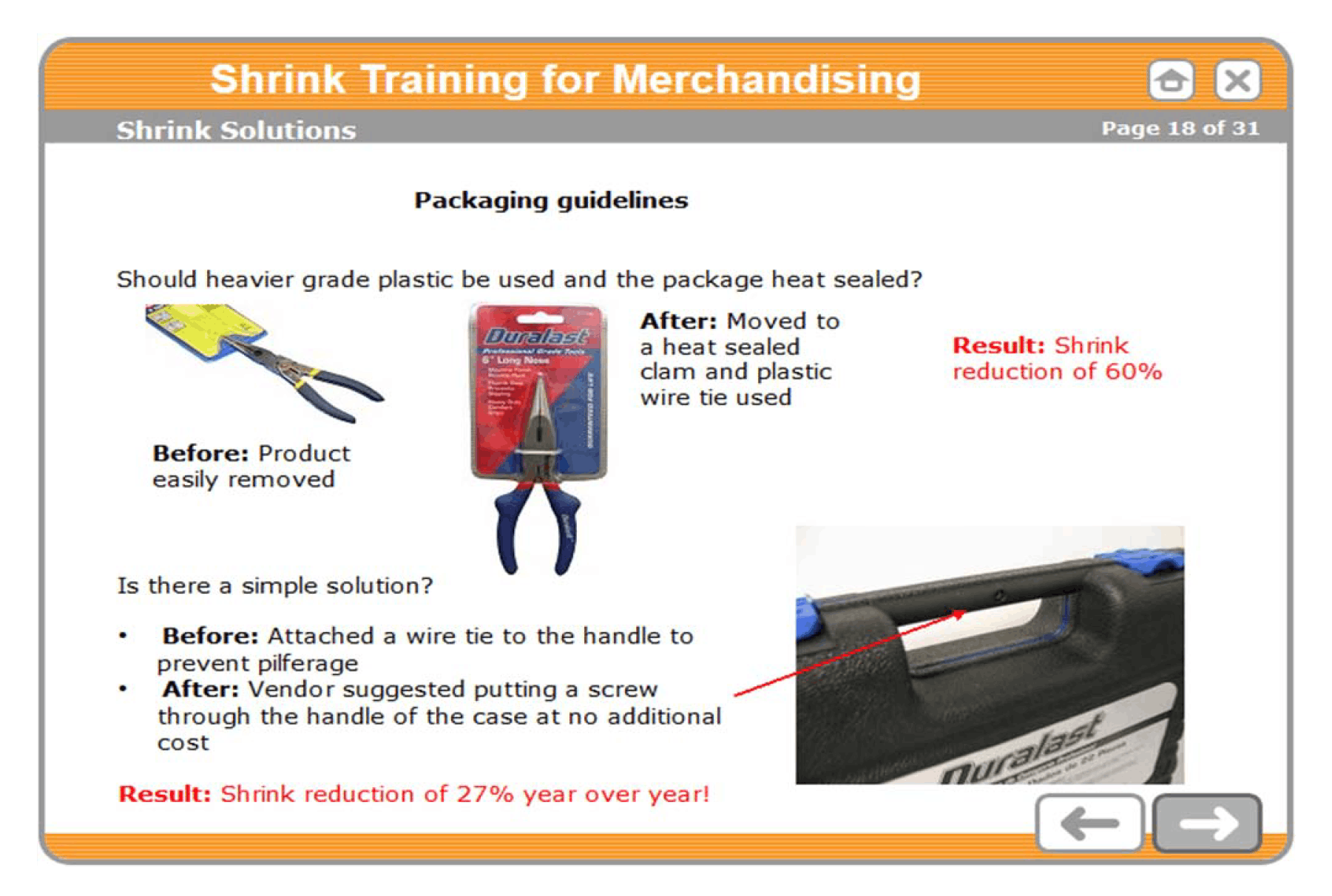

AutoZone is one such retailer that has managed to develop a training tool to explain the importance of asset protection and the types of solutions employed. It carefully makes the case for why merchants should care about asset protection. Moreover, it ties the performance of asset protection team members directly to measures important for merchants such as product availability and lost sales. As Figure 9 below demonstrates, the AutoZone training platform is simple, visual, and based on real‐world examples that link key decisions (in this case packaging) to actual performance (sales or shrink reduction). See Appendix 4 for the full AutoZone case study.

Key partners to retail asset protection teams can also provide assistance. A plausible mechanism for educating retail buyers is for key partners to develop materials relevant to buyers that can be utilized across multiple retail formats. In so doing it pools the investments that would need to be made in individual companies in order to develop material of benefit to all members. Alternatively, key partners could host a workshop dedicated to the sharing of best practice among their asset protection, supply chain, and merchant teams. The objective would be to share best practices of retailing and manufacturing firms known to be on the cutting edge of collaboration when it comes to merchandising, product planning, and execution.

Figure 9: Buyer Training at AutoZone

Changing the buyer’s mindset: Enhanced Analytics

Building the tools to educate the buyers about their role in asset protection is only one step in this process. Our interviews revealed that asset protection teams did not make good partners for the merchant groups. When asked about the strength of their cross‐functional relationships, the buyers we surveyed ranked asset protection in the bottom three. In other words, unlike their relationships with vendors, marketing, and product design teams, they perceived their level of involvement with asset protection as very low.

Moreover, when describing the capabilities of their asset protection teams, only 25% of the buyers surveyed believed their asset protection teams conducts in‐depth analytics to identify the drivers of high shrink items and identifies innovative solutions for the prevention of loss. Instead, the majority of respondents felt that the capability of the asset protection groups was limited to bringing a list of high risk items to review on a periodic basis.

Thus, when merchants did allocate time to the asset protection teams, merchants felt that these teams were great at providing lists of high risk items generated from historical data but that their analytics and predictive abilities were limited. What we heard more often than not was that the merchants didn’t have time to figure out the root cause of the problems generating the top items on these high shrink lists. What they preferred was for the asset protection teams to identify both the problem and a set of solutions from which the merchant could select. This is the way in which the merchants, as CEOs of their categories, interact with other teams across the retail organization and it is their expectation for their interaction with asset protection as well. In fact, buyers perceive the lack of real‐time information and analytics as well as the lack of root cause analysis as two of the top three barriers to collaborations between merchandising and asset protection.

The challenge is that many of the solutions require cross‐functional approaches. Specifically, solutions to poor operational execution require the coordination of numerous functions such as planners, buyers, vendors, supply chain, sourcing, and store operations. As a result, who owns the problem (and thus who is accountable for a solution) is unclear. Any asset protection team seeking to offer long‐term solutions needs to have deep ties to multiple organizational silos and has to be prepared to have to navigate a tremendous amount of social and political resistance.

Beyond fostering and maintaining these relationships, asset protection leaders also need to develop analytical capabilities. This may mean providing additional training to existing team members or hiring specific talent. One big box retailer we interviewed had a sophisticated data driven approach to asset protection. This group tackled critical problems such as items scanned without a proper barcode at checkout (e.g., unidentified sales). It did so by collecting large quantities of data and identifying patterns in these data. Ultimately, they uncovered which products accounted for these losses through analytical detective work and not the kind of detective work traditionally associated with asset protection.

Better analytics can also help asset protection leaders build strong organizational coalitions and improve the perception of asset protection teams as leading problem solvers within the retail organization. For example, one specialty retail chain with whom we worked utilized a data driven approach to demonstrate the value of improved operational execution on category performance. But, their work didn’t end there, this team designed innovative mobile tools to deliver the results of its analytical approach to merchants and store operations professionals alike.

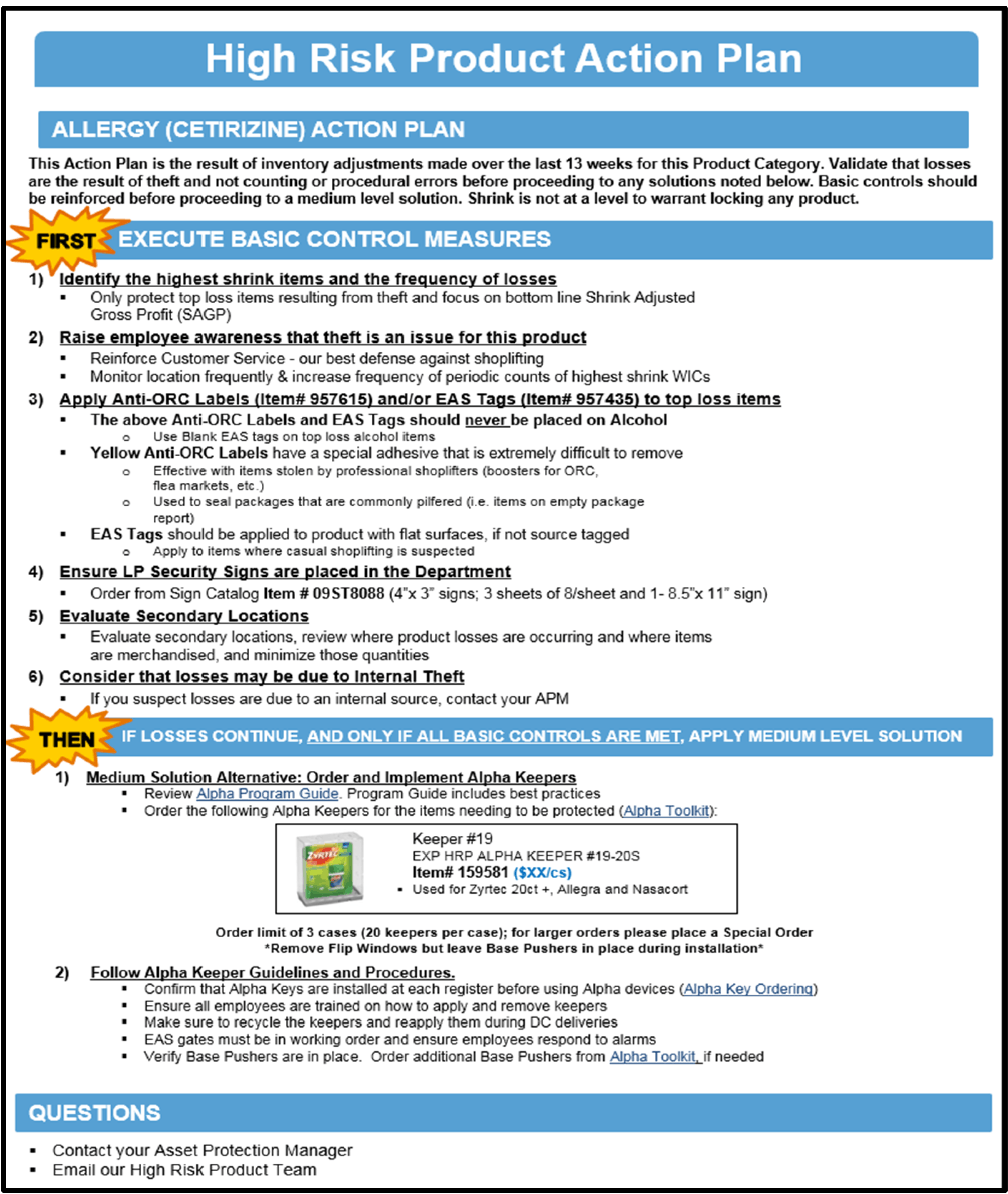

In addition, this team coupled their impact analysis with a menu of solution tools. For instance, if their scorecard identified a problem in a specific product category, their tool would provide a check‐list of actions store operators should take to help mitigate the problem (see Figure 10). After executing on this check‐list, the asset protection team would have better information about what is happening within the stores and could present this information to merchants if their input was required. Overall, this check‐ list was developed after careful analysis and filled an important need for consistency in store execution. In this way, the asset protection team helped build a coalition of supporters throughout their organization.

The need for such innovative analytical approaches will only intensify over time. Asset protection organizations without this capability need to be thinking about how best to obtain the talent and retool existing employees to ensure they can compete. Buyers are looking to asset protection for solutions and solutions require analytical approaches. Using analytics, asset protection teams can test their beliefs about what drives discrepancies in their retail supply chain, can evaluate the impact of strategies designed to prevent such discrepancies, and offer evidence based solutions to buyers and other organizational partners. Such efforts engender trust and confidence in the capabilities of the asset protection organization. Moreover, by moving beyond the generation of high shrink lists, asset protection groups can become far more sophisticated in their approach to solving this problem. Analytics will allow asset protection teams to identify patterns over time, common factors across items that hinder operational execution, and make these teams better able to predict and plan for potential problems. Moreover, armed with such results, the asset protection teams can better inform other parts of the organization, including buying, how their decisions influence metrics such as product availability, shrink, and inventory accuracy in stores and distribution centers.

Figure 10: Sample Action Plan: Generated by Retail Chain’s Asset Protection Team and Used by Store Operations

Current Opportunity

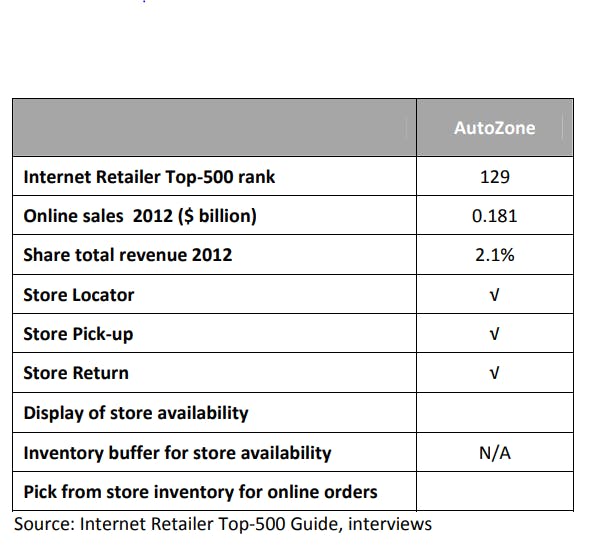

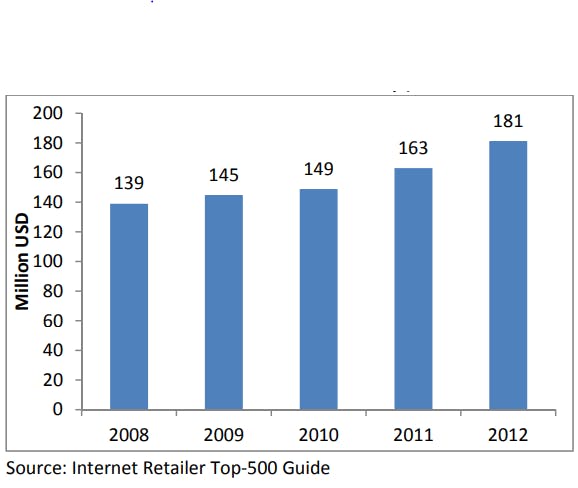

Changing the mindset of buyers will not be easy especially given their workload challenges and the churn present in the buying positions. But, asset protection leaders can capitalize on current retail trends to foster change. Specifically, there is a growing emphasis on operational execution within retailing as a result of the emergence of omnichannel retail strategies. Retail customers expect to be able to buy on‐line, pick‐up in the store, buy in the store and ship to home, and to view the levels of inventory for desired product in their store of choice. Retailers are keenly aware of the need to accurately describe the level of inventory in their stores and to prevent poor product availability regardless of how the customer shops. Asset protection groups ought to be able to capitalize on this increased attention on driving a consistent guest experience across channels. Ultimately, omnichannel is a potential platform for asset protection groups to integrate asset protection and product availability into retail culture, metrics, and analytical approaches.

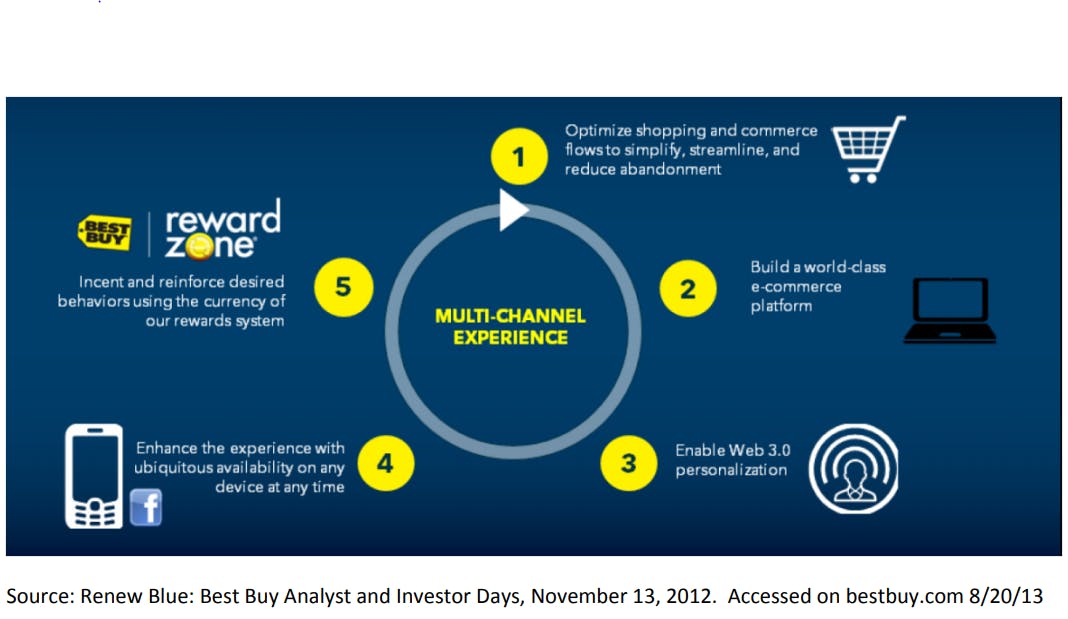

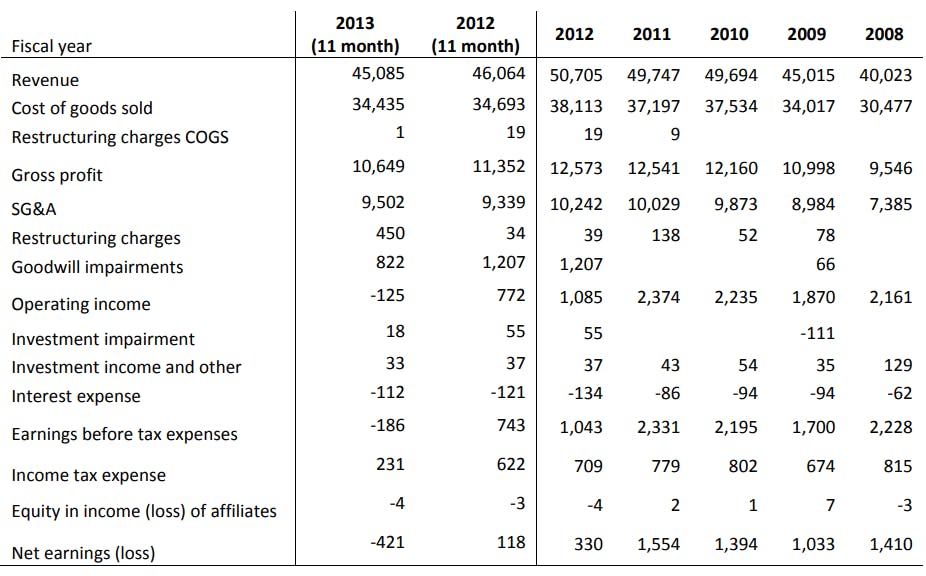

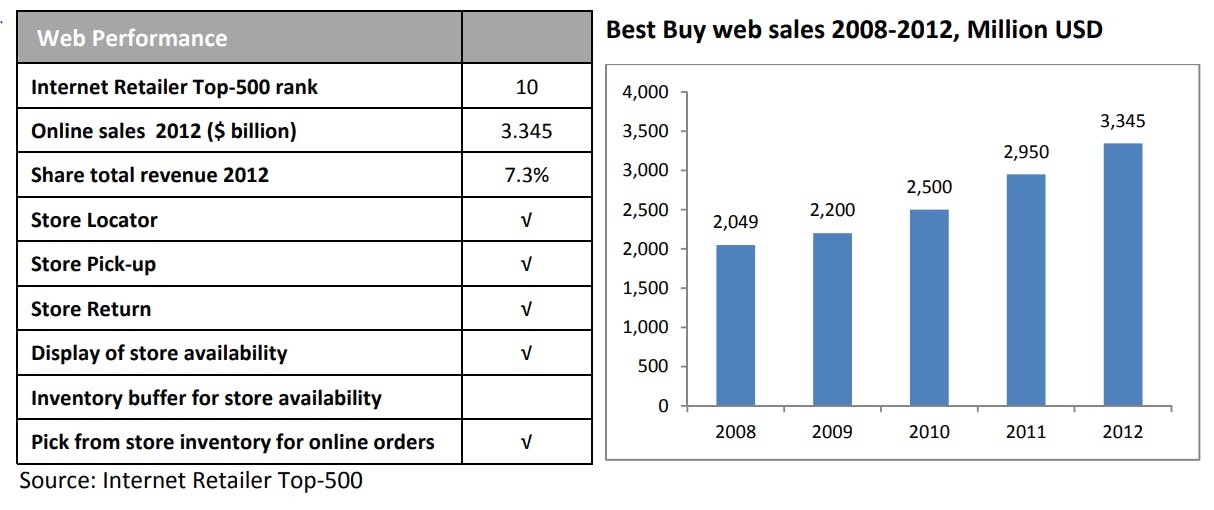

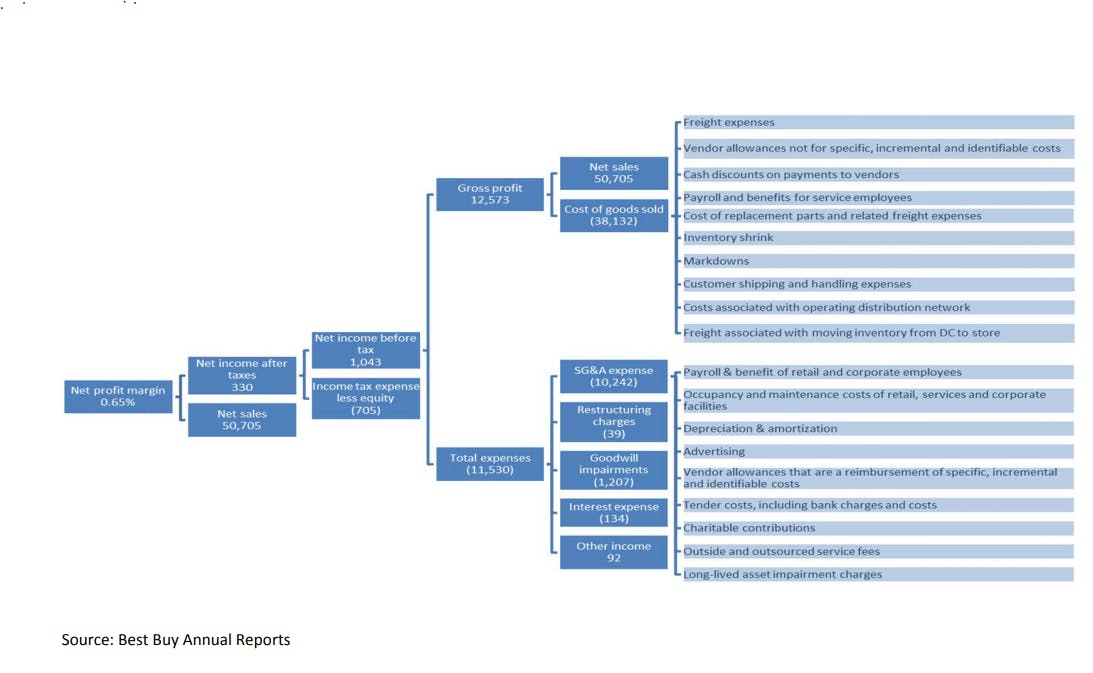

One retailer we interviewed that capitalized on this approach was Best Buy. Figure 11 describes their on‐line strategy (See Appendix 5 for the full Best Buy case study). Best Buy leaders recognized that the conversation was changing within retail organizations such that product availability and inventory visibility were key drivers of omnichannel success. Recognizing their role in ensuring product availability and inventory visibility, asset protection leaders made sure they engaged with those in the organization focused on the customer’s omnichannel experience. As such, they received the attention of numerous cross‐functional groups, including buyers. They helped drive the conversation about the need to incorporate asset protection strategies when redesigning store operations and product flow to accommodate their multichannel approach.

Figure 11: Renew Blue: “Developing a Winning Online Strategy”

Our interviews revealed plenty of opportunity for fraud in the omnichannel space. For instance, at one retailer consumers were able to buy on‐line with a loyalty coupon and if they returned the item to the store they were refunded the full amount in cash due to the divide between on‐line and in‐store systems. At another retailer, none of the store cashiers (or the store manager) knew how to return an item bought on‐line. As a result, they merely refunded the money to the consumer without scanning the item back into store inventory. Examples such as these abound and are a critical reason why asset protection is an essential partner to buyers and planners in the move toward omnichannel.

Moreover, many argue one needs a crisis to generate change. To some extent, asset protection leaders can utilize the pressures retailers are feeling to improve their omnichannel strategy as their crisis to generate change. Asset protection leaders can demonstrate, as Best Buy leaders did, how having asset protection as part of the cross‐functional teams supporting omnichannel strategies adds value. These teams design operational processes, analyze data pertaining to the overall customer experience, and engage buyers to, for example, think about packaging for two delivery types (e.g., store and direct-to-consumer).

Summary of Key Findings

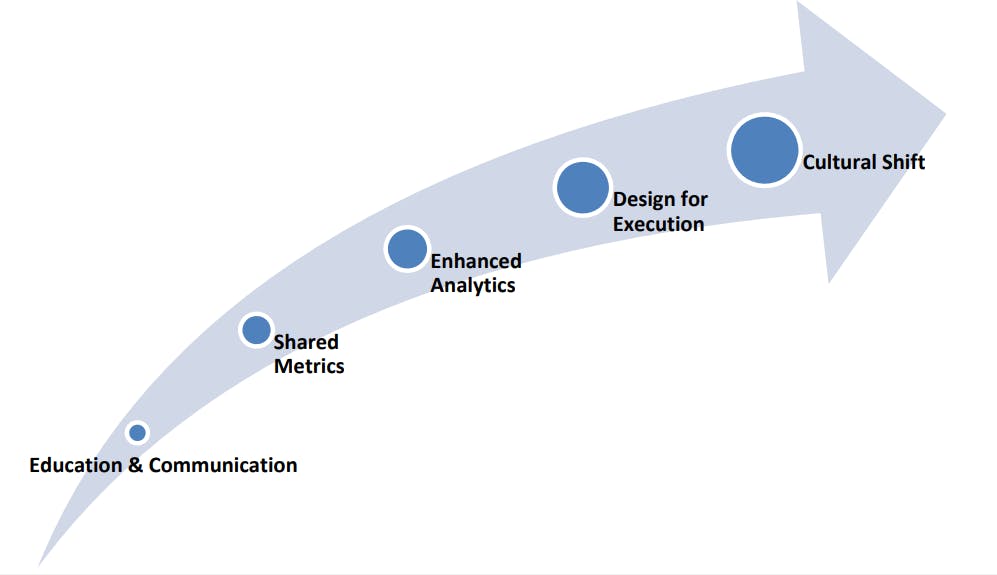

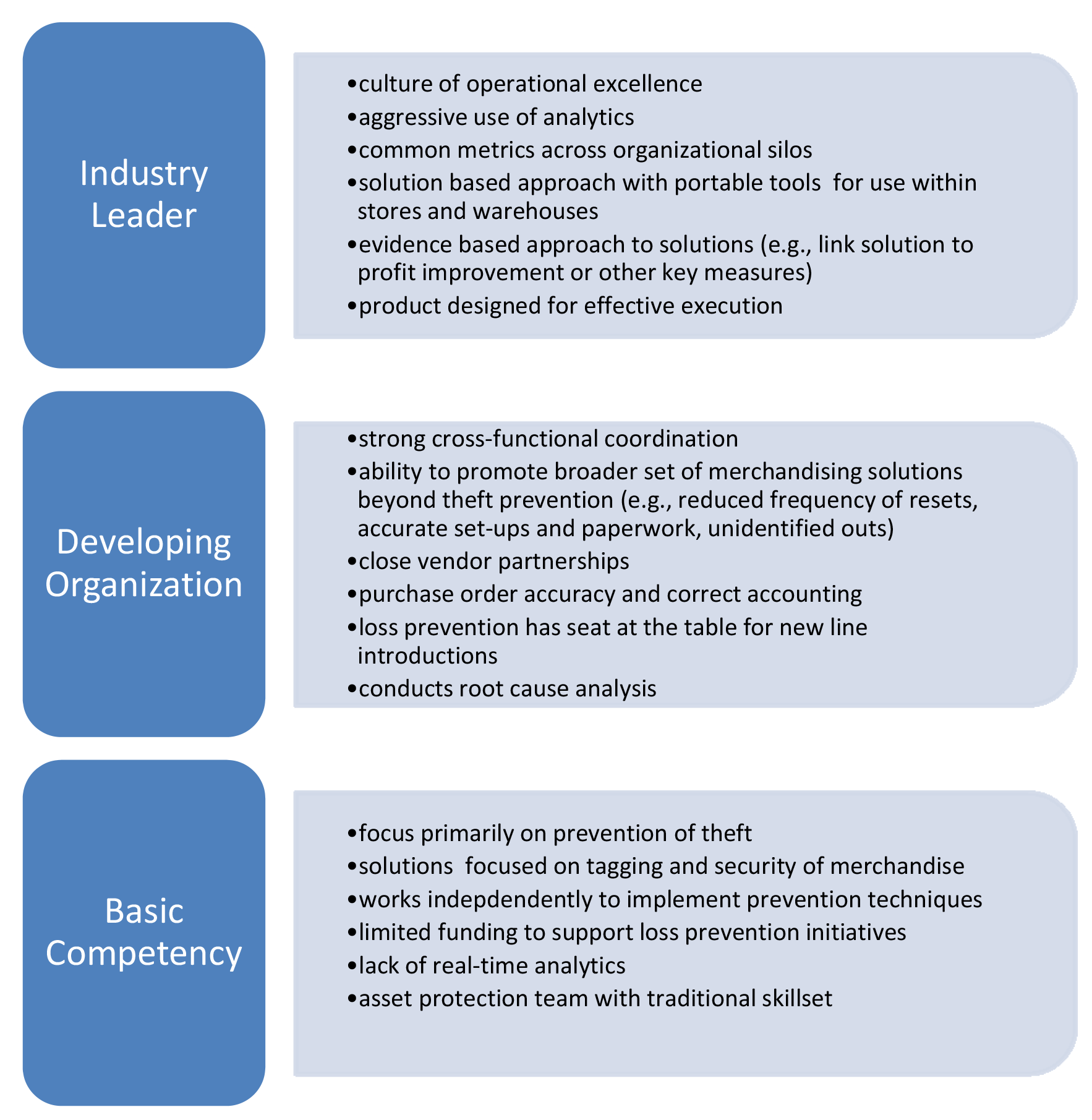

Developing an industry leading approach to asset protection demands dedication, creativity, and senior management support. In the diagram below (Figure 12), we highlight what differentiates retailers with basic asset protection competency to those who are perceived among RILA retailers as world class. Retailers can utilize this diagram to benchmark where they are in their asset protection evolution.

While this figure reveals that there are many steps that need to be made moving from one level to the next, the first and most important step in this process is redefining the retail organization’s notion of shrink. Asset protection groups may continue to be sidelined by buyers and others within the organization if they are unable to broaden their impact. Use of phrases such as profit protection, inventory discrepancies, data integrity, and product availability are ones that resonate throughout the retail organization. For some historical reason, the concept of shrink (and the perception of what drives shrink) actually masks its importance to the organization. Thinking of shrink solely as theft denies the full extent of the problem and the primary solution methodologies employed by asset protection teams – theft prevention – may be inadequate to solving the problem in its entirety.

Why the focus on semantics? Our interviews demonstrated that too few buyers understood how they could influence shrink and how shrink influences their own performance drivers (e.g., buyer incentives). Only one retail buyer emphatically stated “shrink and markdowns are all part of overall profitability…. [and] play significantly into how the profit margin is determined.” Asset protection groups could continue to talk about shrink but given existing perceptions these conversations may not have the desired outcome. Alternatively, asset protection teams can adopt the language of the buyers – a language that emphasizes profit, sales growth, product availability, customer satisfaction – and demonstrate how stock loss impacts each and every one of those variables. Our research highlights the fact that 52% of the buyers surveyed feel that shrink is not clearly defined. This confusion only impedes any progress asset protection wants to make in engaging buyers effectively.

Figure 12: Identifying Leading Asset Protection Strategies

In sum, the asset protection groups of modern retailers exhibit varying degrees of sophistication when it comes to their own capabilities and their ability to engage retail buyers. Of the retailers we interviewed, most qualified as having asset protection capabilities within the “basic competency” or “developing organization” range. Becoming an industry leader will require a step‐change among asset protection professionals. To aid retailers in these efforts, we developed a roadmap to becoming best‐in‐class (Figure 13). This roadmap, derived from our many interviews, identifies the series of incremental steps that comprise the journey from basic competency to developing organization and on to industry leader. Our aim is to ensure asset protection groups do not remain static but rather find themselves on a journey towards improved collaboration and broader impact within their organizations.

Figure 13: The Path to Industry Leadership in Asset Protection

The journey starts with the asset protection team recognizing the need to educate different parts of the organization about the purpose of asset protection and how they (stores, buyers, supply chain, planogram) can influence retail execution. Initiatives that improve education and communication are the foundation of this journey. When it comes to the objective of engaging buyers, the goal is not only to educate buying teams but to learn how best to speak their language. By learning how to more effectively communicate with buyers, asset protection teams are more likely to find they have a seat at the table for critical stages of the retail strategy development (e.g., line reviews, vendor negotiations, reset and new item discussions, etc.). However, having members of the asset protection team whose strength is to listen, collaborate, and persuade may require some changes in the way talent is typically identified and trained within the asset protection teams.

Once this foundation has been built, asset protection teams can start to focus on metrics. Asset protection leaders can identify key metrics for the buying organization such as product availability, in-stock, and measure their performance on these metrics. As omnichannel approaches grow in importance, inventory accuracy metrics will be perceived by most retailers as central to driving sales. Moreover, asset protection teams can help metrics such as total cost of ownership or total landed cost become more widespread within their organizations. Total cost of ownership, for example, quantifies the costs associated not just with product acquisition and purchasing activities but also the costs pertaining to poor quality (rework, return to vendors, labor required to push product to the floor, etc.). Such metrics help all functional areas within the retail organization to value operational execution.

Once metrics have been identified and the tracking of those metrics established, the next step in the journey is data driven analytics. The lack of useful, action‐oriented analytics was a complaint repeatedly expressed among buying teams. Conducting in‐depth analytics is difficult and, as noted above, requires strategic hires. Asset protection groups need to identify not only what are the right questions to ask of the data they collect but how can they convert those questions into recommendations for the present and predictions for the future. It may be tempting to outsource the analytics to third‐parties particularly as the team is just learning about data and how best to collect and analyze it. We observed, however, that many of the firms possessed the capabilities in‐house, namely, among their finance teams. Asset protection teams with strong collaborative relationships with their finance teams often earned the respect of other parts of the organization due to their data driven approach to decision making.

Developing an organization with design thinking is the next phase of the journey. The firm needs to think about how to design its processes and products such it is difficult for employees to make execution mistakes. Such thinking is common in restaurants such as McDonald’s that depends on operational execution to serve the volumes of customers it does with accuracy and speed. Such care and precision can be applied in retail execution as well. In this phase, retailers may need to collaborate extensively with vendors and perhaps even other competing retailers to make improvements that benefit the retail supply chain. There are several examples of competitive collaboration for the good of the industry. For instance, two competing retailers recently collaborated to work with cosmetic suppliers on packaging solutions to improve sustainability performance. The benefit of such collaboration is that it focuses time, attention, and resources to one industry‐wide solution. In the absence of such collaboration, each retailer would take a different approach leading to confusion and additional costs. Take, for example, two different store managers who devise their own shrink prevention solution for a particular category. Without collaboration, these two store managers will most likely offer a solution that can be perceived by the customer as inconsistent and confusing. A thoughtful approach to process and product design is central to this design for execution approach. The objective is to maintain the integrity of the process with as little rework and execution failures as possible.

And, finally, a firm can reach a place where operational execution is embedded in the firm’s culture. The focus on operational execution is pervasive and identifying ways in which to improve the protection of assets is part of the everyday routine rather than an afterthought. In this stage, the role of asset protection teams is more broadly defined. It is less about theft prevention than it is about inventory visibility, process improvement, and solutions for the category manager through the retailer’s supply chain – from vendor to store.

Appendices:

List of Participating Companies

Retailers

- American Eagle Outfitters, Inc.

- AutoZone, Inc.

- Best Buy Co., Inc.

- Costco Wholesale Corporation

- Dick’s Sporting Goods, Inc.

- Dollar General Corporation

- Family Dollar Stores

- Gap Inc.

- The Home Depot, Inc.

- IKEA North American Services, LLC

- J.C. Penney Company, Inc.

- Jo‐Ann Stores, Inc.

- Kmart Corporation

- Kroger Company

- Lowe’s Companies, Inc.

- Nordstrom, Inc.

- Outerwall, Inc.

- Peek & Cloppenburg

- PetSmart, Inc.

- Publix Super Markets, Inc.

- Recreational Equipment, Inc. (REI)

- Ross Stores, Inc.

- Safeway Inc.

- Sears Holdings Corporation

- Sephora USA, LLC

- 7‐Eleven, Inc.

- Target Corporation

- T‐Mobile, USA Inc.

- Ulta Beauty

- Walgreens Boots Alliance

- Wal‐Mart Stores, Inc.

Others

- Kurt Salmon

- Mead Johnson Nutrition

- Procter & Gamble Co.

- RGIS

Appendix 2:

List of Survey Questions

Company/Buyer Information

- Retailer Name

- How many years have you been in a buying role?

- How many unique categories (e.g., running shoes in athletic footwear) do you oversee?

- Approximately how many SKUs do you manage?

- Approximately what % of the overall company buy do your categories represent?

- How many vendor relationships do you oversee?

- What would you say are the leading causes of customer dissatisfaction in your categories? Please rank: Out of stock, Price, Product quality, Selection/variety, Other (please specify)

- Specify your level of involvement/interaction with each of the following (1=very low, 5=very high)

o Auditing

o Buying/Merchandising

o Finance

o Human Resources

o IT Dept

o Legal Dept

o Marketing

o Product Design

o Security/Loss Prevention

o Sourcing/Procurement

o Store Management

o Supply Chain Management

o Vendors

Buyer Incentives

- If you are eligible for bonuses, please indicate the extent to which you think your firm takes into account each of the following factors when determining your bonus. (1‐very much, 5=none) o My category gross margin $

o My category gross margin %

o My category sales

o My category product availability/instocks in my category

o My category inventory turnover

o My category shrink

o My category markdowns

o Other (please specify)

Shrink/Loss Prevention

- What levers do you as a buyer have to reduce shrink? Please list three levers.

- To what extent do you agree with the following statements? (1=strongly agree, 5=strongly disagree)

o Shrink is clearly defined in my organization

o Loss prevention is important/prioritized in our organization

o I always consider shrink in new line introductions o Shrink has a substantial impact on my product categories

o Shrink prevention improves category performance o Shrink prevention efforts have substantial impact on my bonus

o The loss prevention team is a partner in efforts to drive sales o My organization provides me with timely data on shrink levels within my product category

o Product vendors play a key role in loss prevention initiatives within my product categories. - Which of the following statements best describe the capabilities of your loss prevention team? Check all that apply.

o Loss prevention brings a list of high shrink items for us to review on a periodic basis

o Loss prevention conducts in‐depth analytics to identify drivers of high shrink items and identifies innovative solutions for shrink prevention

o Loss prevention advises merchandising teams in advance of a product launch to prevent future shrink problems

o Loss prevention independently implements shrink prevention solutions without merchandising review

o None of the above. - What barriers exist to improve collaboration between merchandising and loss prevention? Check all that apply.

o There is no or limited ROI to shrink prevention solutions.

o Collaboration is not viewed as important

o Individuals too busy o Lack of real‐time information and analytics

o Lack of root cause analysis

o No funding to support LP initiatives

o None

o Organizational silos

o Performance measures not aligned

o Poor store‐level execution of LP initiatives - Does your loss prevention team offer shrink prevention training to the buying organization?

o Yes

o No

o Don’t know - How frequently is shrink prevention training offered to the buying organization?

o More than once per year

o Once per year

o Less than once per year

o Only for new buyers

o Don’t know - Have you attended shrink prevention training in the past year?

o Yes

o No

Appendix 3:

Costco Case Study

Company Background and Organization

Costco Wholesale Corporation began operations in 1983 in Seattle, Washington. The company operates as a membership retail club and offers a limited assortment to their customers at prices below competitors. It also provides members access to various business, consumer, and insurance services. Such services help the company build a competitive edge and sustain its loyal consumer base. It is, however, Costco’s assortment strategy for which the company is known. By limiting the assortment to fast selling models, sizes, and colors, Costco warehouses carry far fewer SKUs than typical grocery or mass retailers. As a result Costco’s retail supply chain does not have to manage the operational complexity that comes with buying, distributing, and merchandising a wide variety of SKUs. A Costco warehouse carries approximately 3,500 SKUs representing six product categories ‐ Sundries7 , Hardlines, Softlines, Food, Fresh Food, and Ancillary Services8 .

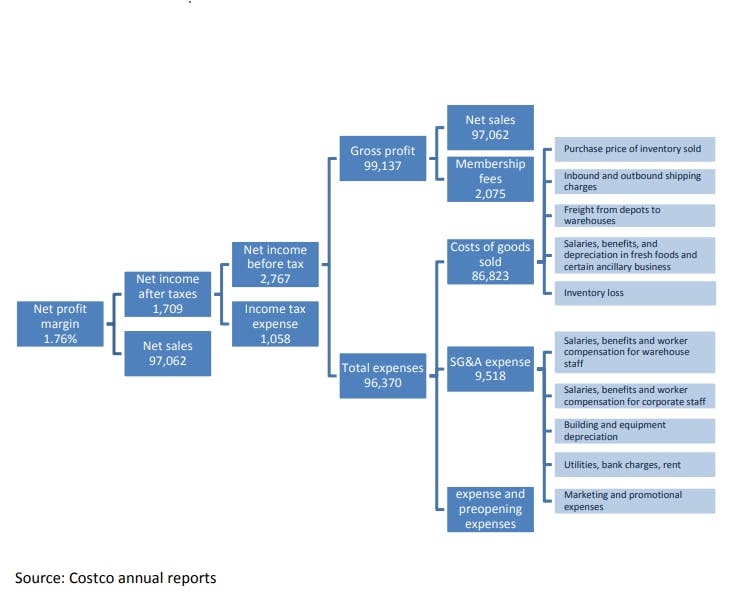

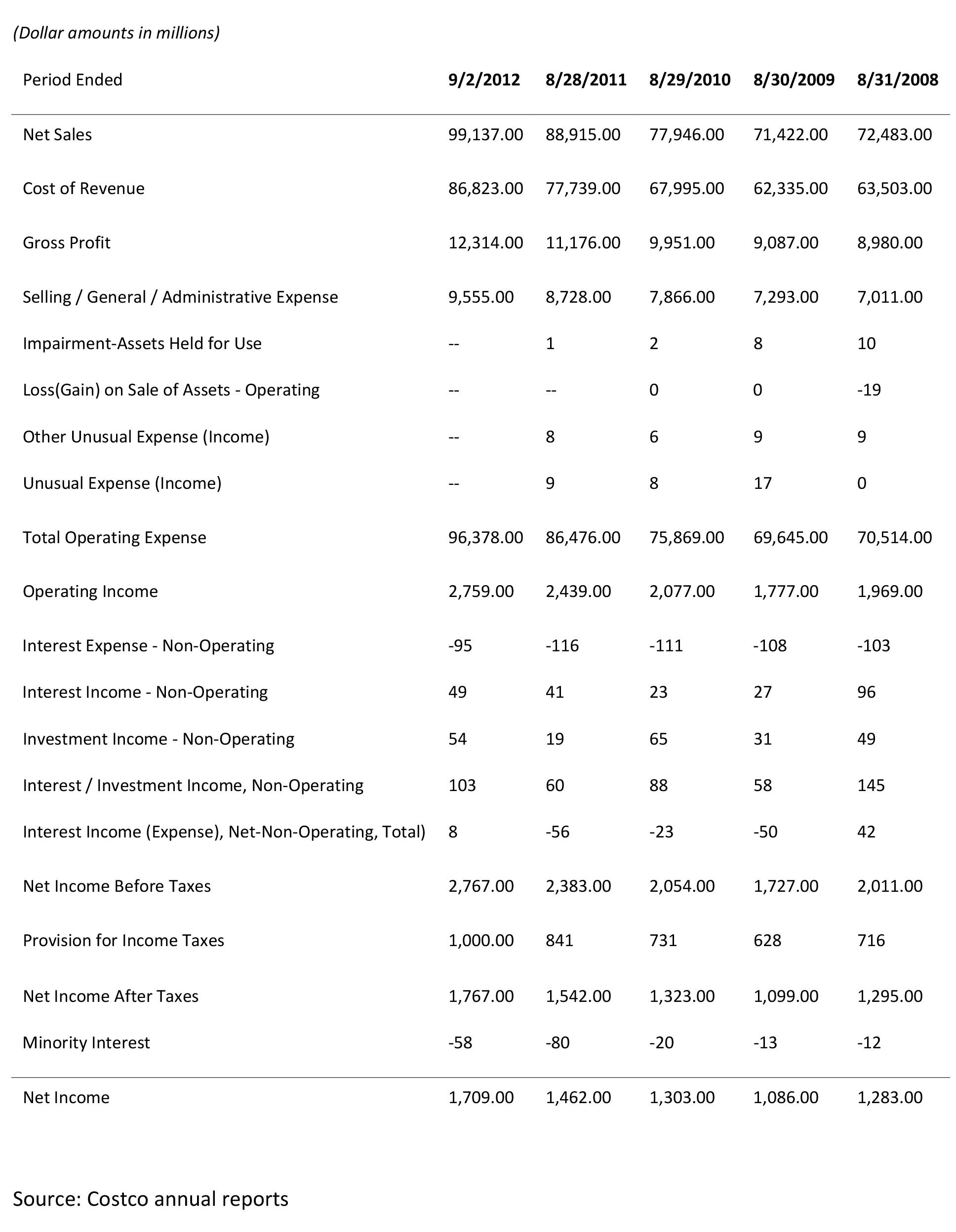

At present there are 37 million households (68 million cardholders) who pay Costco’s annual membership fee. The membership renewal rate stands at 90% demonstrating the loyalty of Costco shoppers who appreciate Costco’s focused SKU selection, value pricing, services, and strong private label offerings9 . It is this membership fee ($55 for basic membership and $110 for executive membership) model that enables Costco, and other club retailers, to maintain competitive pricing by selling merchandise nearly at cost. Net margins at Costco are well below industry average as membership fees contribute substantially to firm profit. 10 With total revenue of $99 billion in fiscal year 2012 – a 12 percent more revenue compared to the year prior – Costco is the sixth largest retailer in the world (see Exhibit 1 for financial summary).11

Costco currently employs over 174,000 people in their 622 warehouses in the U.S. and in eight other countries (as of December 2012). There exists three divisions of U.S. warehouses (Northern, Southwest, and Eastern) and each division is composed of two to three regions. Additionally, Costco operates regional depots (12 depots in the U.S.) for consolidation and distribution of most of their warehouse shipments. Nine Executive Vice Presidents (EVPs) report to the CEO in their various roles in finance, administration, information, merchandising, and international operations, among others. Senior leadership directly involved in the selection, promotion, and delivery of merchandise to depots and warehouses include Merchandising and Distribution. Costco also grants individual warehouse managers significant autonomy to direct in‐store merchandising, promotion, and merchandise displays.

Costco’s corporate culture is rooted in building loyalty with their employees and their members. With high wages, employee benefits, realistic promotion opportunities, as well as overall mutual respect between management and hourly workers, Costco manages to sustain a turnover rate of 5% for employees with one year of tenure (10% if one includes turnover within the first year). This turnover rate is nearly 20% lower than reported in the overall industry12 due, Costco leaders argue, to a sense of ownership among all employees. The strong corporate culture is in turn reflected in satisfied members who benefit from quality customer service provided by experienced and loyal employees.13

Competition

Costco faces significant competition not only from over 800 warehouse club locations across the U.S. and Canada (e.g., Walmart’s Sam’s Club and BJ’s) but also from a range of wholesale and retail market players, including supermarkets, department and specialty stores, discount stores, and online retailers. Competitors with significant market share in the retail industry include Amazon, Kohl’s, Kroger, Lowe’s, Target, Walgreens, Walmart, among others. Costco competes on price, merchandise quality, a tailored selection, retail sites, and member service. While competitors of Costco may have greater financial resources and market penetration not to mention a broader product assortments, Costco manages to differentiate itself through lower prices, better value, and higher employee retention which results in a satisfied membership base. One trade‐off, however, of this strategy is that Costco may not be able to follow consumer trends as closely as their competitors who have larger buying budgets and more flexibility in the planning of assortments and the introduction of new items to the sales floor.

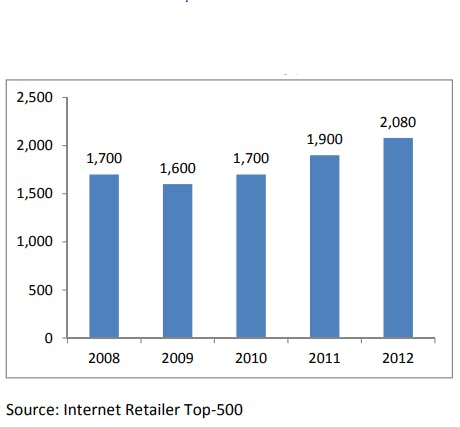

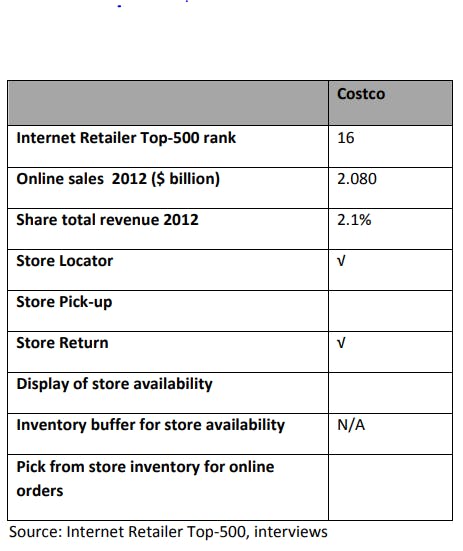

Technology, e‐Commerce, and omnichannel strategy

Costco’s online sales have grown by 10% year over year to $2.1 billion, or 2.1% of total sales, in fiscal year 2012 (Exhibit 2). E‐Commerce sales have been impacted in recent years by Costco club members buying fewer big‐ticket items on‐line.14 Recent initiatives to improve their members’ omnichannel experience include the introduction of Apple and Android mobile applications as well as a revamped and more customer‐friendly e‐commerce website. Products that are available online overlap, to some extent, with Costco’s warehouse assortment. However, the majority of online merchandise offers members product choices not available in the warehouses.15 Costco members do not yet have the option of picking up in the store orders made online, as these orders are shipped directly to a member’s home. Online orders are either drop‐shipped directly to the customer or sent from one of Costco’s three e‐commerce depots. Nevertheless, Costco members do have the option of returning items to either a Costco warehouse or depot. Warehouse returns are then sent to the depot for sorting and redistribution. See Exhibit 3 for a summary of Costco’s current omnichannel capabilities.

The company’s web assortment, which is managed by the e‐Commerce group, is merchandised separately from the assortment found in Costco warehouses. In an attempt to align buyers that deal with the same vendors or order the same items for the web and warehouse assortments, buyers for online and brick‐and‐mortar sales both report to same VP of merchandising.16 Costco’s omnichannel strategy is continuing to evolve as the firm experiments with integrating on‐line with warehouse buying functions.

Mapping the process flow: Costco’s supply chain

Vendor relationships

Costco merchandises national brand‐name products as well as items produced by private label manufacturers. Because buyers focus on each item individually (see section on the purchasing process below), vendor relationships differ at Costco compared to other retailers. Specifically, Costco does not emphasize providing Costco members a specific item supplied by a particular vendor. Instead, the focus is on which item can provide their members with the best value in a specific product category. 17 As a result, no one vendor makes up a significant share of Costco’s total assortment. Products and brands move into and out of the assortment relatively frequently. Moreover, Costco buyers seem to have little concern about finding alternate sources should any of their current supply sources become unavailable.

Vendor compliance tends to be high for Costco’s suppliers. In the case that a supplier is non‐compliant (e.g., fails to meet shipping specifications or on‐time delivery expectations), the supplier may be fined. However, buyers prefer to bring such issues to their management for them to address or to communicate directly with the vendors. The objective is to identify possible solutions rather than penalize their partners. Moreover, buyers may reward vendors who perform well in terms of delivery accuracy and timing by offering them additional SKUs in future orders.

Rather than always return products to vendors, Costco tries to manage products that do not sell by marking them down and sending coupon books to their members – so called multi‐vendor mailers (MVMs) – in order to drive demand. Vendors typically fund MVMs and are common in Costco’s health and beauty department. Other types of vendor funds and rebates include early payment discounts, full refunds for unsold inventory (as in the case of DVDs), promotional funds for prominent placement, and credit for damaged products. One example of the latter comes from Costco’s apparel department, where buyers get a five percent across the board co‐op that covers opened items. Vendor funds are generally recorded as a reduction in the cost of goods sold after the merchandise has been sold or, more broadly, when the established terms of agreement with the vendor have been completed.18

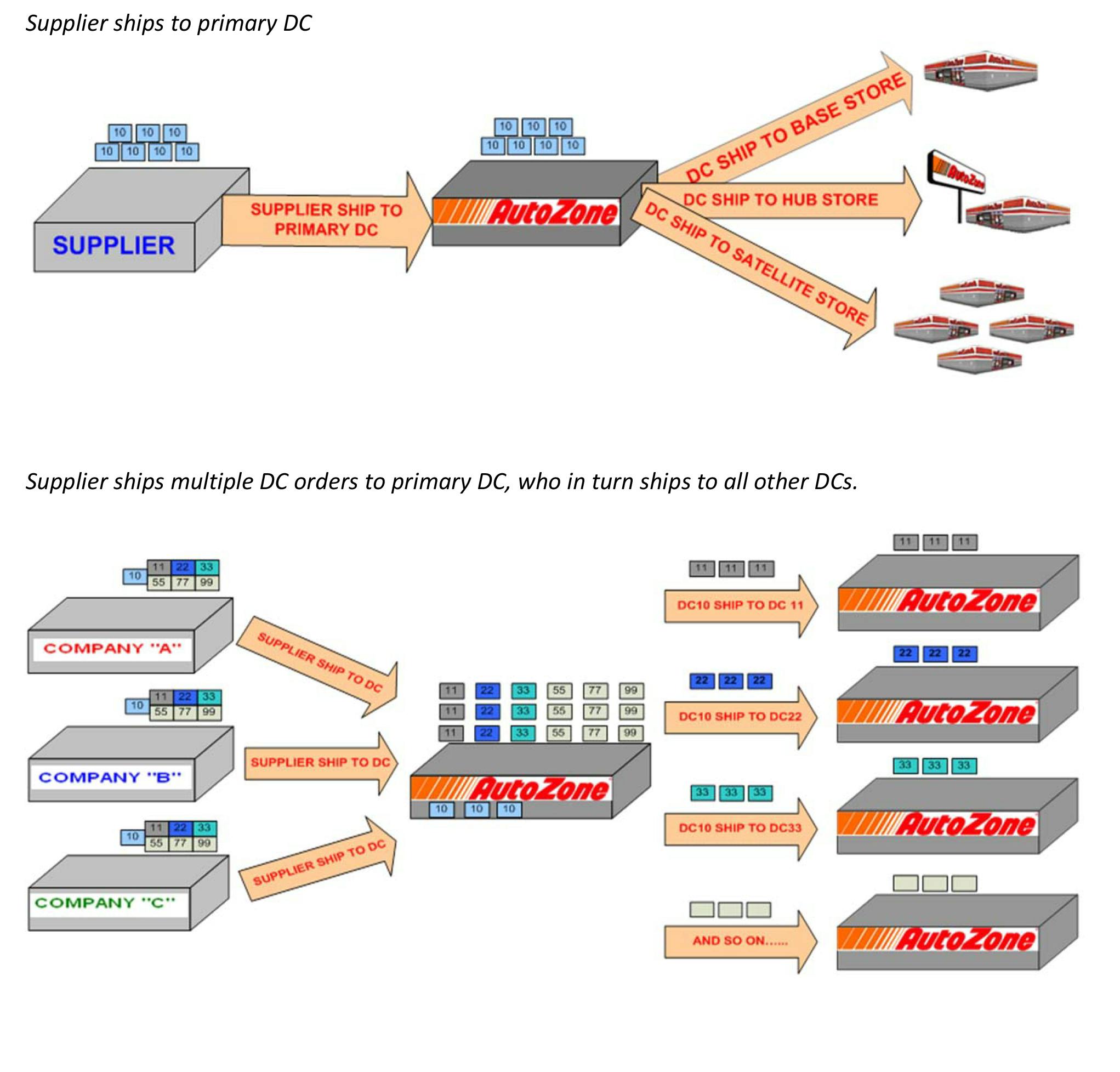

DC‐to‐store inventory flow

Costco sources the majority of its merchandise directly from manufacturers, instead of from distributors. Most items are shipped from suppliers either through one of their depots or directly to the warehouses. The million‐square foot depot facilities serve as cross‐docking points. Inventory is not held or stored at the depots. Instead pallets are received, consolidated, and shipped to warehouses typically within 24 hours. This logistics strategy provides Costco an opportunity to optimize freight volume and minimize handling. This, in turn, keeps operational costs low.

Costco also keeps operational costs low by requiring vendors to deliver items on display‐ready pallets (Exhibit 4).19 This eliminates store labor as Costco employees simply need to unload the pallet from the delivery truck and place it on the warehouse floor. This is a distinct advantage compared to other retailers that need to receive a pallet, unpack it, and then shelve individual items. Such processes require substantial time and labor – particularly for stores with a plethora of SKUs. Moreover, such handling may increase the likelihood of damages, misplacement, or loss. Ninety‐five percent of what Costco sells is sold on full‐pallets.

While the general rule of thumb is that no pallet or location should contain more than one item to avoid confusion among members and employees alike, more than one item may be found on a pallet or in a location at the discretion of a warehouse manager. Usually, this only occurs when a SKU is being discontinued or discounted and another SKU with higher turn gains priority (see Exhibit 5 for examples of split pallets). Avoiding split pallets whenever possible contributes to the prevention of unidentified loss in the supply chain. When there is one item in one location, counting and replenishing merchandise is less complicated than when there are multiple items with similar packaging merchandised in close proximity to one another.

Costco communicates with vendors through a “Structural Packaging Specification” handbook that details the requirements of these pallets and product packaging. This document, among other things, identifies in detail the size, strength, and material composition of any pallet, product packaging, or shipping material that is permissible within the Costco supply chain. Failure to comply with these specifications can lead to a penalty (e.g., 2% chargeback) or even the delisting of a vendor’s item. Regardless, all new items will be rejected upon delivery should prior deliveries be found in violation of Costco specifications. At this point in time, buyers will, as noted above, intervene to attempt to solve these issues. Any stoppage of product flow means that the performance of their product category suffers.

Throughout all its documentation and communications with vendors, Costco makes it very clear that its supply chain extends all the way to the warehouse floor and vendors need to consider not only the quality of the items they are bringing into the warehouse but also the quality of the packaging. They require packaging that can withstand movement within the Costco supply chain but also convert to merchandising displays that are attractive and informative for members and that provide easy access to individual items. Overall, the clear focus even within this supply chain function is on optimizing member experience while controlling costs. This is a goal that seems to unify this organization and provides an overarching objective towards which all functions can contribute.

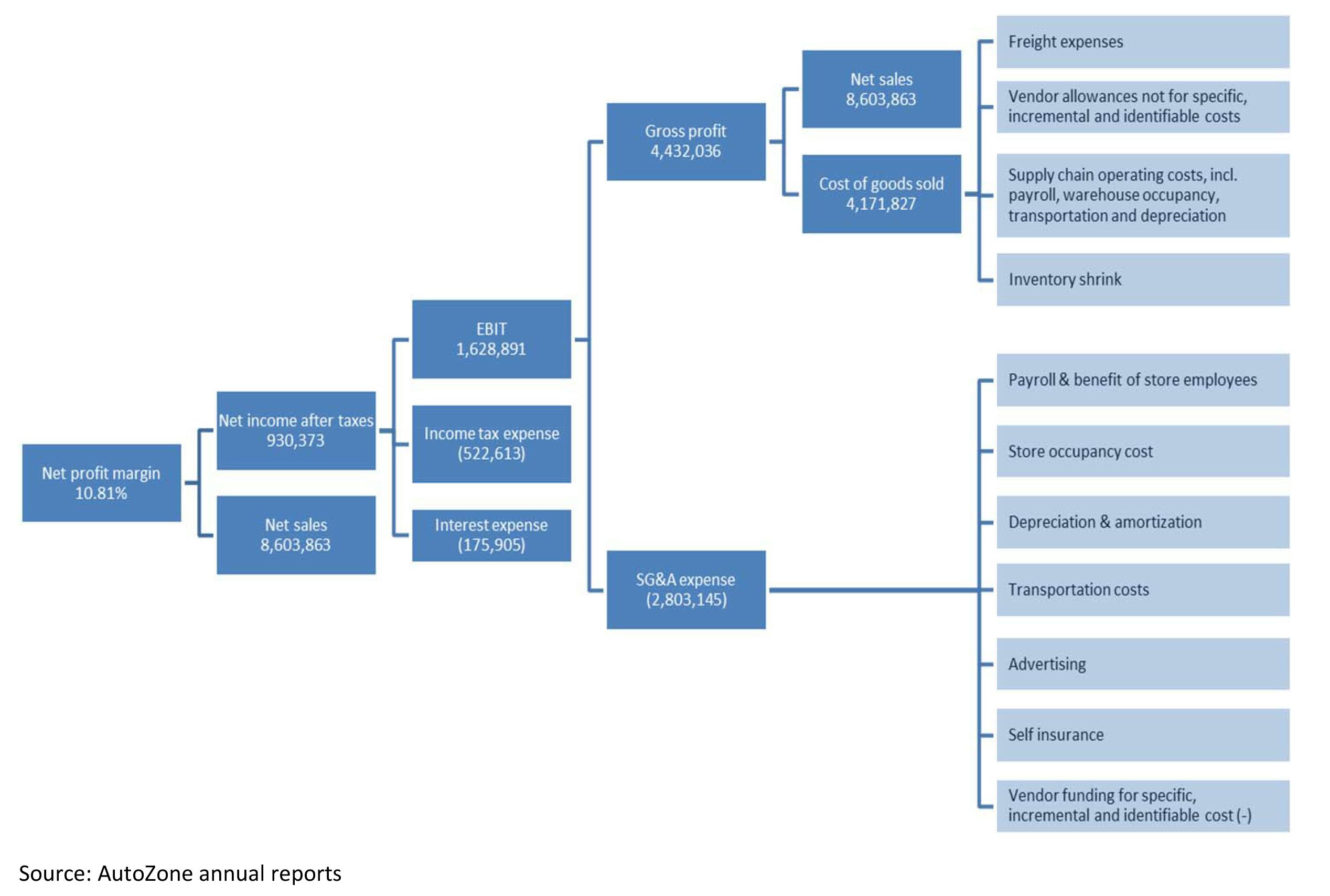

Costco’s distribution strategy, which requires less handling and stocking, along with other efficiencies derived from their warehouse‐style store set‐up (e.g., shorter hours of operation, minimal display racks, limited hanging, etc.) offer significant cost saving opportunities relative to more traditional retail operations. This is reflected in the low selling, general and administrative (SG&A) expenses at Costco, namely 9.81 percent of net sales in fiscal year 2012 (see Exhibit 6 for the breakdown of Costco’s key cost components in their profit structure, including its SG&A). At Costco, SG&A consists of salaries, benefits, and workers’ compensation for all warehouse staff20 as well as regional and home office employees and utilities, bank charges, rent, asset depreciation.21

The purchasing process

Costco’s merchandising groups are multi‐layered and vary in size and level of responsibility across regions and categories. At the corporate level, buyers are organized in five groups: General Merchandise Managers (GMMs), Assistant GMMs, Buyers, Assistant Buyers22, and Inventory Control Specialists (ICSs), each of which is responsible for one or several product categories. The GMM is in charge of making strategic decisions at the department level and for approving the final assortment together with the Assistant GMM. The latter is also responsible for Costco’s category‐level strategy for their assigned items. The Buyers at Costco are the main decision makers in selecting SKUs for the assortment, setting prices, forecasting overall volume, and determining distribution quantities for individual regions. They are also accountable for hitting their weekly and annual category sales and budget targets, and for conducting item Line Reviews (see below). The ICSs set up purchase orders (POs) in the system, communicate these to the vendors, and make sure that items are in stock. Exhibit 7 depicts the decisions in the merchandising and distribution of goods made by buyers and other key groups within Costco retail supply chain.

The buying group has a parallel structure for regionally sourced items that to a large extent resembles the structure in corporate. The fresh foods category, for instance, which is largely sourced at a regional level, is managed by Regional Buyers, Assistant Regional Buyers, and Regional ICSs. These employees operate out of regional offices, and decide on how best to manage inventory and in‐stock in terms of volume and allocation. They also rely on warehouse managers to identify needs in the local market (e.g., a warehouse manager may suggest a local food manufacturer).23 Other categories, such as apparel, will only have regional ICSs.

These groups work together such that the purchasing process follows one of these three paths. Corporate decides what to order and regions decide how much. Corporate allocates products to regional depots and regions decide how to allocate within the region. Lastly, regions receive vendor‐ allocated inventory directly according to corporate direction and regions decide how to allocate within the region.

The selection of merchandise by buyers follows a structured process. Buyers hold regular Line Reviews with vendors in order to go over new items, analyze prospects of sales, growth, and pricing structure. The frequency of Line Reviews varies significantly by category, starting at once per month for fashion and seasonal merchandise such as apparel and foods. Line reviews occur with some frequency as do new set‐ups. Nearly every single week, buyers are putting new products into Costco warehouses in order to keep members from being bored and to create the ‘treasure hunt’ atmosphere desired by Costco leadership. Note that new SKUs will often be tested in the warehouses before the buyer decides to create the PO. This usually involves an eight‐week test period in 25‐40 buildings selected by the buyer24. Frequent resets also have operational benefits in addition to member benefits. Costco used to have the majority of their new items enter the warehouse at the beginning of a selling period and then the warehouse would sell through these items until the next period. With re‐sets occurring each week, it not only keeps the inventory fresh and exciting, it helps balance the flow and required workload. Instead of needing to ramp up space, labor, transportation, receiving, etc. for the start of each selling season, there is now a steady influx of new items that can be readily managed by existing staffing levels.

Buyers’ bonuses are based 50 percent on corporate performance and 50 percent on the specific department’s performance. Key determinants of bonus include sales, margin, growth, and inventory turns. GMMs are additionally incented on shrink targets.25 Buyers argue, however, that sales tend to drive everything because the cap on margins means little variability across items in margin. GMMs allocate buyers a certain number of spaces in a category, also known as pallet positions, and they then determine what the best use of that space is. They often have productivity targets – a minimum threshold of sales per week per warehouse per item – they have to meet to keep a product in the assortment. Each item has to stand on its own and to justify its own space. These buyers follow a few key rules, namely, sell nothing below cost, do not exceed a margin of 14%, for non‐food items, and try to order in full pallet quantities.

Costco buyers argue that their roles are far less complex than the jobs of their counterparts at other retailers mainly because they need only focus on 60‐80 items compared to 2‐3,000 items. With so few items, it is really easy to quickly look at the performance of each item daily and, when needed initiate research to determine if something is going wrong. Moreover, buyers state that they require little computerized support to conduct their analyses given their focus on each item rather than shopping baskets. They perceive their ability to manage and manipulate the raw data an advantage as it provides them first‐hand knowledge of their category.

By focusing on fewer items, buyers have the time to evaluate each item in more depth. Specifically, buyers can focus on how their decision impact operational factors. They do so in part due to incentives and in part due to the understanding of warehouse tasks and empathy for warehouse employees. Buyer margins at Costco take into account not just the negotiated price26 of an item but also the net landed cost – or how much it costs to get the item all the way to the warehouse floor. Thus, buyers, when setting up an item, are trying to figure out how to get the item from the factory to the warehouse as efficiently as possible. Buyers can impact this decision through the choice of packagers (vendor packaged versus utilizing a third party packer), buying in truckloads, pallets, etc. Buyers even go so far as to focus on the SG&A required to sell the product. They often think about how much time and effort will go into stocking and item because the sales need to offset those payroll dollars.

Costco buyers have often spent many years – even entire careers – within different roles on the buying teams working their way up from the ICS position and gaining experience across categories. Worth noting is that nearly all members of the buying team enter through the ICS position. Therefore, the buyers understand the inventory flow process and the challenges that can arise with product replenishment. The length of time the buyers have been with the company, and within their buying roles, is seemingly unique among retailers. It is not unusual to meet buyers who started as an hourly in their local warehouse and thus have a deep understanding of the operational challenges faced by stores in the movement, sale, and merchandising of items. This frontline experience among those buying and planning inventory engenders a respect for operational execution. Moreover, because of this experience, they understand how the decisions they make as buyers (product selection, type of packaging, display choices, new item introduction, pricing, etc.) can influence the productivity of each warehouse location by making an item easy to merchandise, keep in stock, sell, and rapidly replenish.

Product availability at Costco

Inventory management, cycle counting, & shrink

Costco’s inventories are valued at the lower of cost or market, determined by the retail inventory method, and are stated using the last‐in, first‐out (LIFO) method for U.S. merchandise, whereas foreign operations are stated using the first‐in, first out (FIFO) method.27 It is important to note that Costco does not track items by color or size28. An item gets one number regardless of its color and size. This causes challenges not only for accurate replenishment but also for managing and identifying inventory shrink.

Costco measures inventory shrink by taking the difference between actual and expected inventory levels at the item level, valued at retail, as a percentage of net sales. All merchandise is counted twice a year. In addition to the semi‐annual inventory adjustments associated with these physical inventory audits, Costco‐employed auditors do periodic inventory counts (cycle counts) in the warehouses once per week, with a new category chosen at the discretion of the warehouses for counting each week. The cycle counts are summarized in bi‐annual shrink reports that are developed by the company’s Financial Accounting group under the direction of the Comptroller. These reports include a list of top‐25 shrink items and are shared with the warehouses. Cycle counting results are also presented by the GMMs in the monthly budget meetings for executives from specific regions and departments.

Buyers believe these monthly shrink reports to be somewhat ad‐hoc in that the items counted are not chosen systematically so an item might show up in the top‐25 because it was counted by a warehouse whereas another item, with shrink issue, might not be on the list because it wasn’t selected for a count. Buyers do, however, rely frequently on the pictures sent to them by warehouse managers to identify which colors of an item are selling more rapidly than another or sizes that might be missing from a pallet so that the buyer will send some more of those colors and sizes. This manual process is in place to mitigate any product availability problems that might arise due to shrink or inaccurate replenishment due to the lack of style‐color‐size visibility.

Shrink is presented as a line item in the annual budget, based on the company’s experience and past results. Shrink is also present on the monthly budgets managed by buyers. Buyers, however, argue that this line item rarely fluctuates and thus it is not often taken into consideration during any of their line review meetings. What does garner more addition from buyers is the damaged and destroyed line item on the budget. This line item is maintained separately from shrink and it primarily captures returns. Returns at Costco, like at most retailers, represent a substantial problem within some product categories. Returns could be due to quality problems, buyers’ remorse, or a product that is too complicated to assemble or to hook up. The adoption of the Costco concierge service aimed to help members with complicated electronics set‐ups reduced returns dramatically but not enough to draw attention entirely away from the challenge of returns.

Shrink prevention at Costco

Costco acknowledges that internal and external theft is only one component of shrink and estimates this accounts for 50% of their overall shrink. Inventory markdowns and process failures such as receiving errors, concealed shortage (e.g., inner‐carton shortage), undocumented destroyed, unauthorized use, and front‐end errors comprise the remaining 50%. Overall, shrink is relatively low at Costco, with an annual shrink rate 0.1 percent of net sales in 200929 and less than 0.25% of net sales at present30. Any product category with a shrink number of 1% or greater is considered “big” and garners managerial attention.