Mobile Self Scanning Technologies: Understanding the Impact on Loss

Executive Summary

This report presents the findings of an ESRC-funded study conducted between December 2013 and February 2015. The primary focus was to identify current developments in mobile scanning technologies in the retail space; to understand how allowing customers to use their own personal mobile phones to scan and pay for items could impact upon shrinkage and also identify how crime prevention might be integrated into these systems. The methodology was based around interviews with staff involved in the development and implementation of mobile scan and pay systems across four retailers in the UK, two in the USA, one in Belgium and one in Holland. Loss prevention staff were also interviewed and analysis of shrinkage data from one retail partner was also conducted.

The key findings are:

1. Development and Perceived Benefits of Mobile Shop and Pay

- Mobile scan and payment is at an early stage of development across most retailers. At present, the focus is mainly on developing a mobile scan option only rather than one that also enables payments to be made via an App (a mobile wallet option).

- There is some evidence that customer appetite for MSP is limited. Indeed, there was a suggestion that in some locations and for some demographics the move to MSP might represent a cultural shift that could be slow to be adopted.

- The potential benefits for customers are thought to be numerous. Not only could MSP make shopping easier and quicker – through the elimination of the need to use traditional checkouts – it can also offer ways to ‘personalise’ the shopping experience. This can be done by offering consumers the opportunity to create shopping lists, view their purchase history, receive information on real time store offers, have access to store maps and product searching functionality, and receive and use electronic vouchers, all through an App on their mobile device.

- Respondents also identified numerous potential benefits for retailers. MSP could enable more staff to be utilised away from checkouts and on to more customer-focussed services such as in-aisle assistance. It also offers the potential for a reduction in the overall staff hours allocated to stores and the costs associated with using and maintaining traditional checkout technologies. MSP was also thought to offer greater opportunities to provide customers with forms of loyalty bonuses and exclusive product offers, and to collect valuable data on shopper behaviour to better inform future business planning.

- The research found that there are a number of technological and process challenges that need to be overcome before MSP can be rolled out across most forms of retailing. At present MSP systems are normally limited to Apple devices, Apps can run slowly and scanning barcodes with a mobile device can be difficult. The shopping process is slowed down when age restricted products, or security protected products are purchased (as a member of staff has to intervene). At present, the lack of a payment wallet option means in most retailers that0 MSP users still have to find and use a fixed payment terminal, undermining the perceived benefits of speed and ease of use.

2. The Potential of MSP to Generate Retail Losses

The research found that MSP might generate retail losses/problems in four ways – theft through malicious non-scanning of goods; non-malicious loss through non-scan/scanning errors; physical and verbal abuse against staff generated via audit checks or system errors; or transaction frauds/fraudulent use of payment wallets. In summary:

- MSP potentially promotes ease of effort for theft by removing any human contact throughout the shopping process and removing (possibly most importantly) human contact at the final payment stage of the shopping journey (when a payment wallet option is provided). In the MSP environment, the sense of risk perception or control is reduced as all elements of the customer journey can be completed without human interaction. Some respondents thought that offenders might be attracted to stores in the knowledge that they can chose to not scan certain products with relatively little risk of being caught.

- MSP gives offenders ‘ready-made excuses’ for non-scanning behaviour – the self-scan defence. Giving customers the freedom to self-scan gives them the opportunity to blame faulty technology, problems with the product barcodes or claim that they are not technically proficient as reasons for non-scanning.

- Proving intent is difficult where customer nonscanning is identified and deciding whether prosecutions can be made or not is potentially a legal and customer relations minefield. It is proving difficult for retailers to identify whether customers intended to non-scan items or if they were simply absentminded and or poor at scanning items consistently. This could be further compounded when the point of payment becomes blurred by consumers having the option to pay at any location within and potentially around the store.

- MSP could also generate provocations for aggressive behaviours. At present, there are a number of frustration points in the MSP shopper journey that could trigger disputes with staff – when products will not scan correctly, when staff have to intervene to remove EAS devices/do age verifications, when payment wallets will not work and when a check audit is requested.

- There were some concerns around the potential for fraudulent activities, including the production of self-scan labels that might be stuck on products and the potential for fraudulent payments. It was thought that the payment wallet could generate fraud such as being used with stolen credit card details or the use of fraudulent electronic vouchers or coupons via this type of technology.

- Concerns were expressed that non- and misscanning of items could have a detrimental ‘knock on’ effect in relation to inventory accuracy and on-shelf availability of stock. Thieves are notoriously unreliable when it comes to updating stock levels when they take products and customers may not readily appreciate the impact of scanning the same item multiple times when a range of similar varieties are actually being purchased.

- Available data indicates that mobile scanning technologies, including MSP, generate significantly high rates of loss (3.97% as a percentage of turnover), more than 122% higher than the average rate of shrinkage – greater than the typical profit margin (approximately 3%) of the European Grocery sector. The data suggests that if these rates of loss are typical then this type of ‘service’ is not likely to generate a high profit margin unless other areas of cost can be reduced to compensate for the inflated rate of loss generated, or users can be encouraged to scan a higher proportion of selected items.

3. Risk Amplification

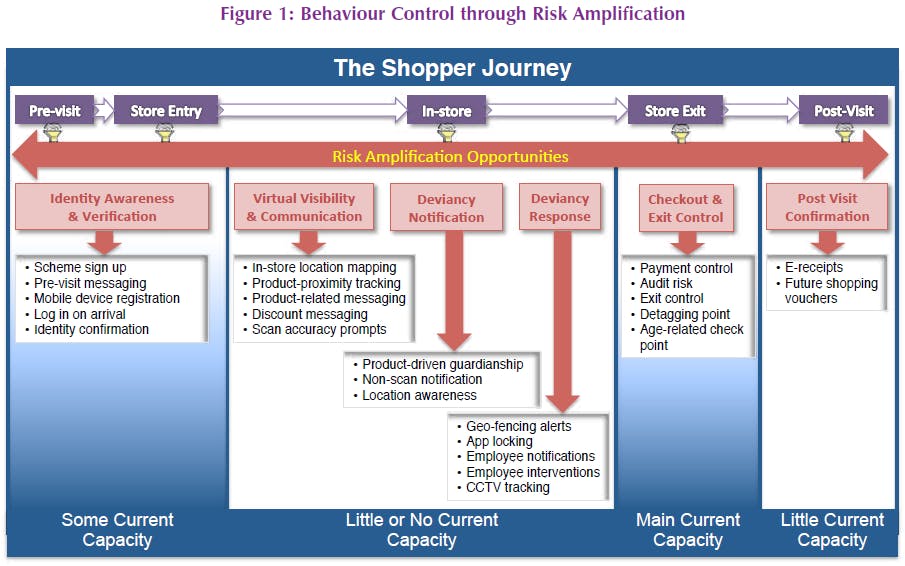

A key aim of the study was to consider what crime prevention mechanisms were already in place to prevent MSP-generated losses and what future mechanisms might need to be considered. Our main observations were that:

- Very little developmental work had been put into fully understanding how the risks associated with MSP would be addressed beyond utilising the existing approaches. Without fully understanding what the risks might be, it was hard for retailers to consider what additional crime prevention solutions might be considered and what costs could justifiably be attributed to them.

- Current measures being used by the retailers taking part in this study focussed almost exclusively on the extremes of the shopping journey: store entry and the payment/checkout process.

- It was observed that, for the most part, the registration processes currently being used were open to easy manipulation through inputting false information, including the potential to use stolen credit card details.

- The only other risk amplifier currently available was the ‘random’ audit check. The process for doing this varied significantly between the retailers taking part in this study but all thought it was their most powerful weapon in generating risk in the MSP shopping journey.

- Integrating existing product protection devices into the MSP process is problematic as deactivating tagged products require staff interventions – which goes against the ethos of MSP.

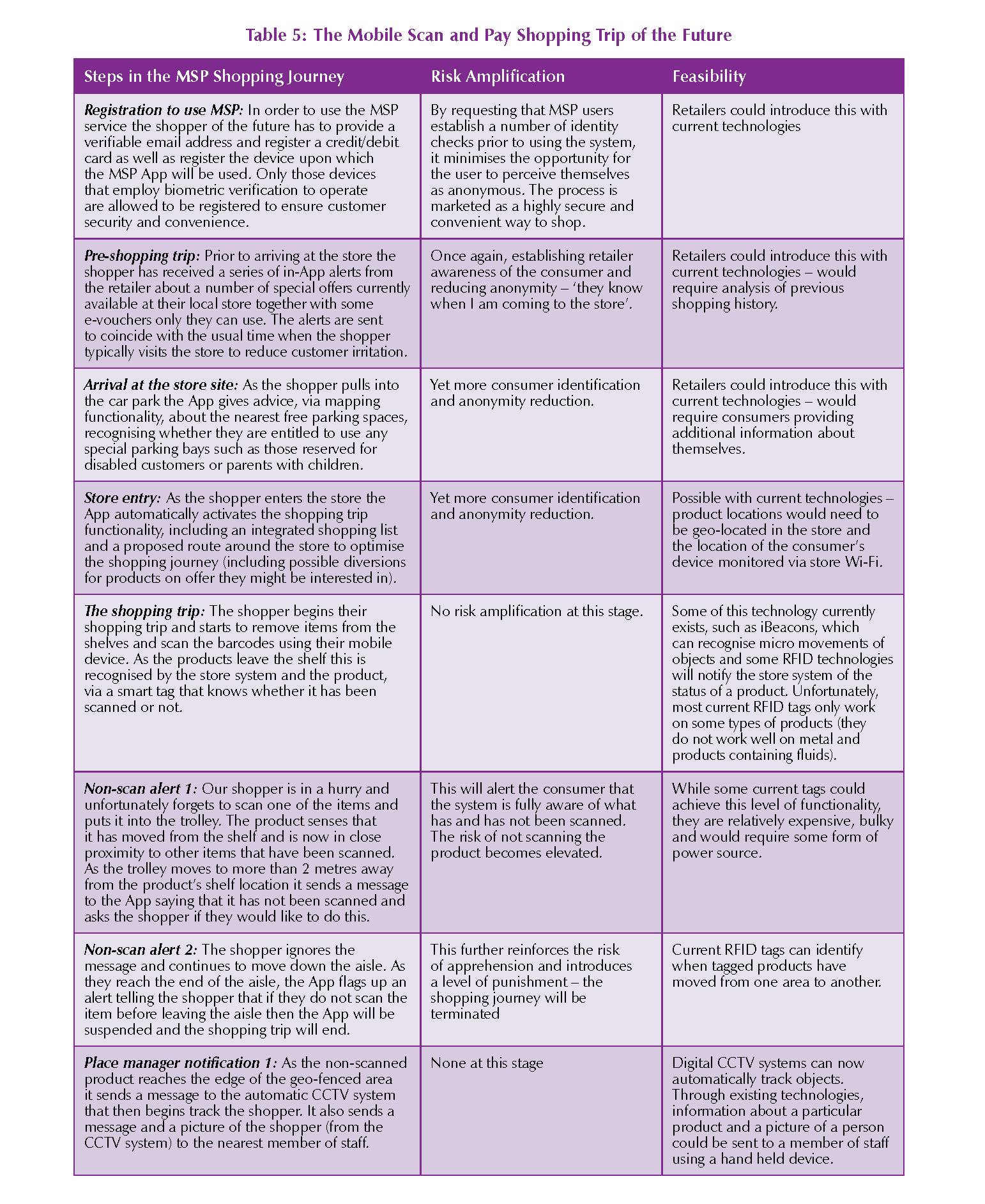

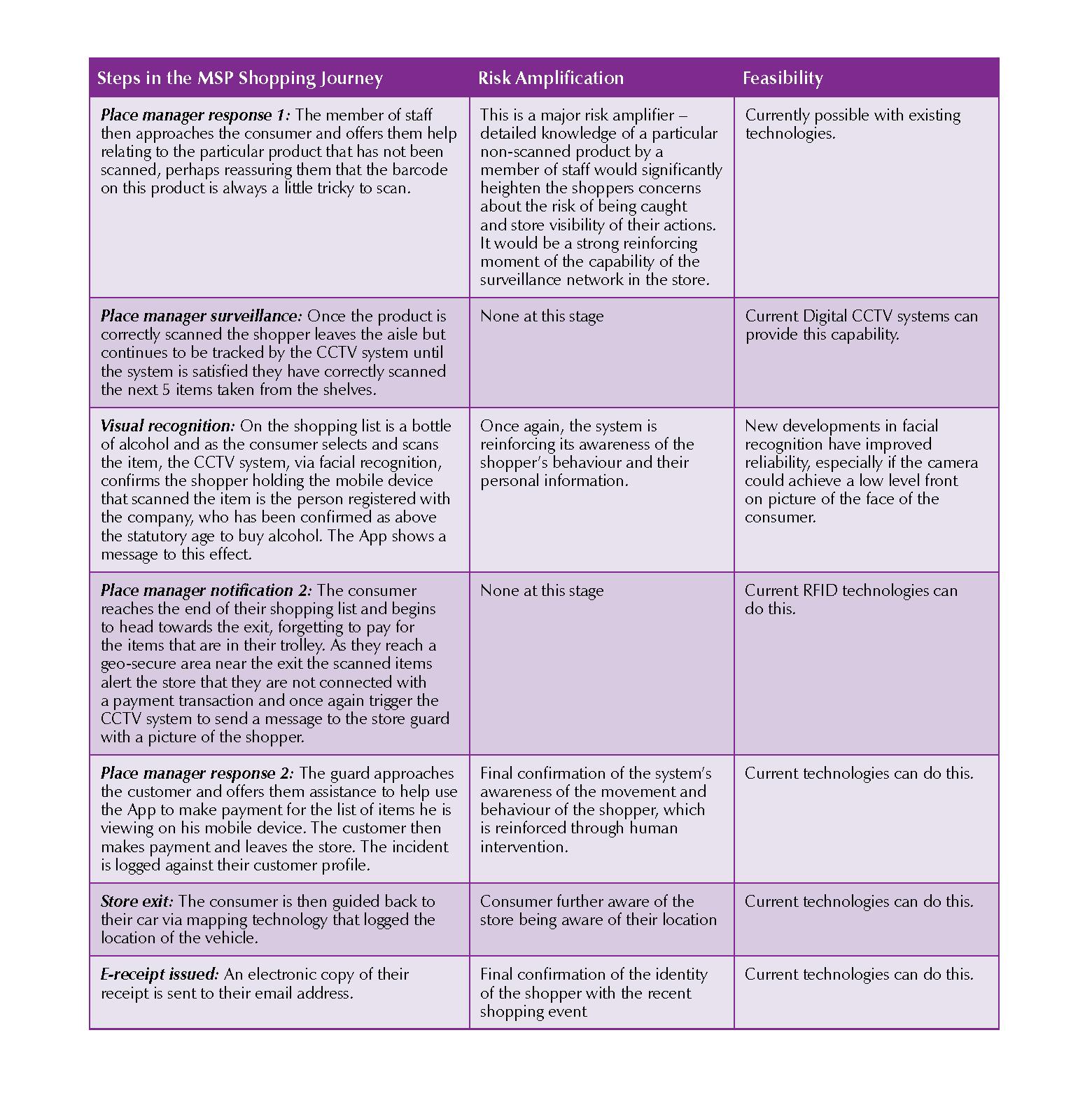

- In future, risk could be amplified throughout the MSP shopping journey in a number of ways. For example, a series of retailer/customer messages (via the App) at arrival and entry to the store could reduce customer anonymity at the start of the shopping process. During the shopping trip non-scan alerts could notify shoppers and security personal if products have not been scanned. Visual recognition CCTV could be used to conduct age restricted checks. Geo secure areas could be used to monitor payment compliance.

- Current technologies can already deliver some of the requirements required to increase risk in the steps outlined in this report. CCTV systems can communicate with information databases and micro location monitoring can already be seen in some retail spaces. The challenge is developing a tag that can enable the majority of consumer products to communicate with their environment – RFID tags have been found to offer this potential but on only a relatively small range of products. No other tag technologies seem to be able to offer this type of capability at this moment in time.

1. Introduction

This report presents the findings of an ESRC-funded study conducted between December 2013 and February 2015. The primary focus was to identify current developments in mobile scanning technologies in the retail space; to understand how allowing customers to use their own personal mobile phones to scan and pay for items could impact upon shrinkage and also identity how crime prevention might be integrated into these systems. The main aims and objectives were framed around the following research questions:

- How mobile self-scanning technologies might be used to facilitate shop theft – what new opportunities for deviant behaviour can be identified?

- How might current and future loss prevention technologies (such as CCTV, EAS and other forms of product protection) need to be adapted to minimise the risk of losses from mobile self-scanning?

- Given our current understanding of the importance of generating perceptions of risk and utilising the concept of a zone of control to achieve this, how will this be generated when customers use this technology – will there be a need to undertake random audits for instance?

- How will ‘surveillance’ operate within the store to ensure customer compliance? Can a ‘virtual zone of control’ be created either via the App or through for instance changes in store design and procedures?

- How will any existing legislative requirements on the prohibition of the sale of certain products (such as alcohol) to minors be managed?

- In what ways should retailers consider the design of current and future stores to take account of the risks this technology might generate – for instance how customers enter and leave?

- How should store and security staff be trained to recognise potentially deviant self-scan behaviour – will there be a need to create new store roles such as roving mobile scanning assistants for instance?

- Should new technologies be developed/introduced to facilitate the identification of self-scan facilitated deviant behaviour and if so how might it work?

- How robust will systems need to be in order to cope with errors/problems such as unreadable barcodes, battery failure, lack of Wi-Fi connectivity, customer-initiated voids, price reductions, voucher scams, incorrect scanning of items and the misrepresentation of goods at weighing stations?

The work focused upon developments in UK-based retailers, though the research was also mindful of international developments in this area. Thus, while the fieldwork was initially based upon detailed interviews and store visits across four UK based retailers, interviews and store visits were also conducted with two USA, one Dutch and one retailer based in Belgium.

This report is structured into the following sections. First, we outline the background to the work and the theoretical basis for the study. Second, the methodology is presented. Third, the key findings are outlined and finally, we consider the implications for crime prevention and potential areas for further research.

2. Background to the Study

2.1 Innovation in Retailing

Although most innovation in retailing commonly aims to expand customer markets and increase shopper convenience, it can also generate loss. Within retailing, three principal phases of innovation in customer experience can be observed, with a fourth currently emerging. The first marked the move from primarily behind the counter service, with dedicated staff selecting the goods customers wished to either view or purchase, to open display where the customer could self-select items from open displays and then take them to a central point for purchase. This approach was pioneered by the Grocery sector in the early to mid-part of the 20th Century and has eventually been adopted by most parts of the industry. It was seen as a way of improving the customer experience through offering the opportunity to interact with the products available for sale and it also acted as a major catalyst for innovation in packaging design, brand management and store layout.

The second major development was the introduction of self-scanning technologies where customers not only have to find and select items themselves, but they are also expected to take responsibility for payment as well at dedicated self-scan checkouts. Initially introduced in the 1980s, again primarily in the Grocery sector, it did not see much industry role out until 2010 onwards, mainly due to the limitations of the technology and little perceived customer appetite for this type of shopping experience.

The third development marked a move towards offering mobile commerce and online shopping. Mobile commerce (m-commerce) allows customers to search and pay for products online via their own computer, tablet or mobile device and either have products delivered to an agreed address or collect them from a physical store at an agreed time. It has been noted that m-commerce is a rapidly growing market that currently represents 12% of all US e-commerce sales (Walsh, 2013). Halliwell (2013) suggests that the Smartphone is becoming a key part of the retail experience across the world and it is predicted that spending via mobile devices will double worldwide from £920 billion in 2013 to over £2 trillion by 2017 (see Clark, 2013). While some are predicting a future where the Smartphone eventually replaces the physical store1, the 2013 Agile Customer Survey (see Halliwell, 2013) of 1,000 British shoppers identified that 54% of customers already use their mobile phone to compare prices online and 46% to research product information. Thus, for many, the mobile phone is becoming an integral part of the shopping process but not necessarily replacing entirely the traditional shopping experience of visiting actual stores – the death of the high street is much quoted but perhaps overstated at this time (Duncan, 2014; The Independent, 2013).

The move to mobile commerce is very much connected with the emerging fourth development (the principal focus of this report) of offering the customer the opportunity to use their own mobile device ‘instore’ to not only scan items they wish to purchase, but also pay for them using the same technology, through the use of downloadable Smartphone Apps, anywhere in the store. While uptake at the moment is rather patchy and focussed primarily on the Grocery sector, some believe that this is the next major development in the ever-changing retail landscape (McKinsey & Company, 2014).

The move to develop and introduce mobile scan and pay (MSP) can be seen as part of long-term changes in the retail industry that have seen increased customer autonomy and self-service at the expense of formalised staff/customer interactions. For example, the move from counter-service to self-selection at the beginning of the 20th century allowed customers to find, select and pay for items of their choice. Curtis (1971) notes this change gave economic benefits to retailers – fewer staff needed to be employed, and the store design could be radically changed to maximise the display of goods, which led to significant increases in sales and retail profits. However, there was a price to pay – this more open and less controlled retail style made it not only significantly easier for motivated offenders to steal products, it also reduced perceptions of risk for all customers, encouraging more to think about taking advantage of the new opportunities for deviancy presented to them (Beck, 2009). The development of self-scan technologies in the 1990s and 2000s then allowed customers to not only self-select items but also expected them to take responsibility for the scanning and payment components of their shopping trip as well. Beck (2011) argues that this brought yet more opportunities for retailers to reduce costs as fewer staffed checkouts were required, but it also required a considerable leap of faith in the integrity and honesty of the shopper as they needed to be trusted to scan all items they wished to purchase. Although current evidence of the impact of self-checkouts on retail losses is inconclusive (see Taylor, 2013: Beck, 2011; NCR, 2012), it has been suggested that it has created significant opportunities for loss by yet further reducing the sense of risk perception for customers (and would be offenders) in store.

2.2 Mobile Scanning Technologies: Previous Research

Although several articles on MSP have appeared in retail trade magazines (see for example Halliwell, 2013), only two academic studies have considered the benefits and risk of mobile technologies in retail (see Taylor, 2013; Aloysius & Venkatesh 2013). Four key findings emerge from these studies:

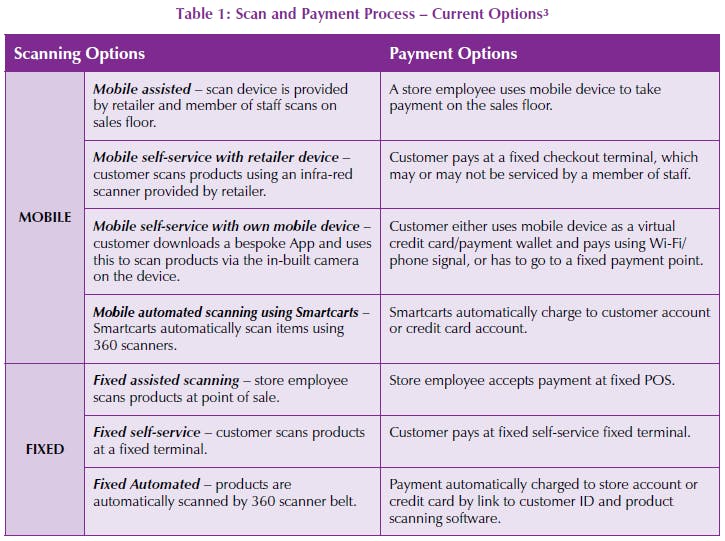

1. There are several potential configurations of scan and pay: a number of potential scan and payment configurations exist including a variety of fixed and MSP options (see Table 1 for an overview). This makes any analysis of how loss/crime might be generated in the mobile shopping journey more complex than for the traditional customer journey (which was a linear process – browse, select, scan, pay) as products may now be scanned and paid for throughout the shopping process (Taylor, 2013).

This also means stores may now have different types of shoppers in-store at any one point – the traditional shoppers who scan and pay at a staffed checkout; those who self-scan and pay at a fixed terminal and a new breed who want to self-scan on a mobile device and use this device as a payment wallet.

2. There are several technological/process issues with MSP still to be resolved: Aloysius & Venkatesh (2013) and Taylor (2013) highlight several process/ technological issues with MSP systems that present a risk to the shopping journey. For example, poor Wi-Fi connectivity and insufficient phone battery life may interrupt the shopping journey. Concerns have also been expressed about problems customers might face when attempting to self-scan goods (evidence from self-scan research suggests this can be problematic – see for example Beck, 2011). Indeed, Baxter-Reynolds (2013) comments on a trial of mobile scanning in a major retailer where it was found to be difficult to align product barcodes to the camera of mobile devices, the system did not recognise multi-buy offers and payment was via a normal fixed payment till, which slowed down the purchase process. Crucially, how MSP will work with existing forms of product protection – such as Electronic Article Surveillance (EAS) tagging and safercases – and how products that are age-restricted will be purchased via MSP (without the need for stopping customers) also still have to be resolved (Aloysius & Venkatesh, 2013; and Taylor, 2013).

3. Customer appetite for MSP and confidence in systems is questionable: questions have been raised over the customer appetite for MSP and customer confidence in the systems that operate the security of payment wallets. It has been suggested that if sold to customers as a form of convenience shopping, then it is necessary to ensure that customers are confident that systems function smoothly and that security around payment is guaranteed. The evidence to date is that some customers feel current MSP systems are slow and not a particularly convenient way to shop (see Baxter-Reynolds, 2013). However, Aloysius & Venkatesh (2013) and Taylor (2013) also note concerns remain over the appetite of customers to use their own mobile phone to scan and pay. While some have concerns over liability for loss of their phone or data on their phone, Walsh (2013) suggests that persuading customers that secure payments can be made via their mobile phone will be a significant challenge.

4. The potential impact upon loss and shrinkage is unclear: shrinkage is commonly understood to include external theft, internal theft, process or administrative errors and inter-company fraud (Chapman and Templar, 2006; Beck, 2014). No studies have estimated the amount of shrinkage that MSP could generate, but it has been noted that (as with SCO) the opportunity for nonscanning of items increases: customers walking through exit barriers with goods scanned but not paid for (walking), employee-aided loss and collecting receipts to steal or return goods later (see Taylor, 2013; Aloysius & Venkatesh, 2013). There are also possible fraudulent uses of MSP, in particular in relation to payment wallets. Other malicious problems might include the intentional misuse of vouchers and selecting the wrong loose items description (carrots instead of grapes scams). Non-malicious losses might be generated through ‘honest’ mistakes where items did not scan because of a technical glitch. While a body of research has identified a number of opportunities that MSP might generate for loss there has been little systematic study of these risks or any attempt to ascertain if shrinkage is indeed higher in stores where MSP options are in place.

2.3 Theoretical Basis of the Study

The previous research is useful as it identifies some of the practical process and technological problems with MSP and how opportunity for loss is generated. However, there has been little attempt to analyse the criminogenic opportunities generated by MSP through any appropriate criminological theoretical/explanatory framework or to identify how either physical or onlinebased crime prevention mechanisms might be built in to the shopper journey. Based upon these observations the framework for our analysis of MSP is broadly based around three well-known theoretical concepts that are outlined below.

Opportunity Theory, Techniques of Neutralisation and Risk Perception

Many academics argue that much criminality is a result of offenders taking advantage of opportunities for crime that arise in their everyday routine activities (Clarke, 1980; 1992; 1997; Clarke & Homel, 1997). Opportunity theory is thus based on the notion that offenders make rational choice decisions to offend and when exposed to a potential crime opportunity, choice structuring decisions around the effort required to commit the crime, the risks of getting caught and potential rewards on offer are made (Cornish & Clarke, 1986). This simplistic framework clearly offers a useful structure to aid our understanding of the proximal factors that might influence how MSP could generate crime and loss in the retail environment. Indeed, much criminological research has already shown that the propensity to steal is a function of the amount of effort required to commit the crime, the anticipated rewards (the goods/items available to be taken), perceived likelihood of being caught and the perceived severity of any likely subsequent punishment (Cornish & Clarke, 1986). Crucially, in relation to shoplifting, Cardone & Hayes (2012) illustrate how offenders’ decision-making is closely related to the perceived effort required to successfully commit the crime (access to goods, ease of escape) and perception of the risk of getting caught (which is amplified by the presence of CCTV, number of ‘place managers’ or employees in store or security personnel).

The move from counter shopping to customer selfservice (and latterly MSP) has, however, complicated matters in relation to proving the intent, motivation and rationale of the non-paying customer – did they actively seek to steal products or are there contributory factors which need to be understood in order to correctly frame the event? While the move to MSP might offer greater opportunities for theft, it also offers greater opportunities for customers to make not only genuine errors in an increasingly complicated and technologically driven process, but also generate ‘excuses’ for non-payment through the use of neutralising techniques (Sykes & Matza, 1957; Cromwell & Turman 2003). Indeed, Beck (2011: 211) notes that in relation to SCOs, proving guilt on the part of the offender is difficult as they have a series of ready-made excuses – ‘I thought I had scanned that item’ or ‘I thought my credit card had been accepted’.

Such techniques of neutralisation might not only be developed by those not intending to pay for goods, but might also be used in circumstances where customers can feel justified in taking items if SCO systems do not operate smoothly – thus enabling customers to construct what they perceive as legitimate excuses for theft (Beck, 2011). However, Aloysius & Venkatesh, (2013: 36) also note this might not only lead to discrepancies over what losses are malicious and nonmalicious, but also ‘erroneous customer accusations’ – can stores realistically seek criminal prosecution when a non-scanned item is found in a customer’s bag when the retailer expects them to use SCO technologies?

Questions therefore remain about how MSP generates such opportunities for crime and the extent of loss that may be malicious (purposeful theft) or non-malicious (errors either due to customer or technology failings). However, further exploration is required around how opportunities for malicious or non-malicious loss might be blocked. Indeed, a wealth of crime prevention literature suggests that when new products or systems are designed efforts should be made to identify what potential crime opportunities might be generated (Felson and Clarke, 1998) and to design out such generators of crime (Ekblom, 2012). Traditionally crime prevention has aimed to reduce crime through using opportunityreducing techniques (see Smith & Clarke, 2010) that:

- Increase the effort for motivated offenders through target hardening, access control, exit screening, deflecting offenders and controlling facilitators.

- Reduce rewards through target removal, property identification, benefit denial, removing inducements and disrupting markets.

- Increase risks by extending guardianship, promoting natural surveillance, reducing anonymity, utilising place managers and formal surveillance.

- Remove excuses through reducing frustrations and stress, avoiding disputes, reducing emotional arousal, neutralising peer pressure and discouraging intimation.

- Removal of provocations through rule setting, clear signage, alerting conscience, assisting compliance and control of drugs and alcohol.

As Aloysius and Venkatesh (2013: 6) note, ‘surveillance and control become more difficult in the mobile scan world’. Indeed, current crime prevention thinking is largely based around blocking opportunities using existing physical methods. For example, Taylor (2013) and Aloysius & Venkatesh (2013) make useful suggestions based upon existing solutions (such as CCTV, tagging and RFID) and processes in stores (such as validation checks)4. However, there is a failure to identify how these preventative measures might be integrated in to the MSP shopper journey and whether they have a realistic prospect of actually impacting upon perceptions of risk.

Thus a key challenge is to design crime prevention in to a system where existing notions of the shopping journey (browse, select, go to checkout, scan (self or by staff member), remove any product protection, pay and leave) are severely challenged, as are the traditional ways in which risk is generated and amplified. For instance, if a consumer is legitimately entitled to ‘scan’ items and pay anywhere in the store using their own device, without interacting at any time with a member of staff or fixed technology, how can ‘risk’ be injected into this type of shopping experience – what will stop the MSP shopper taking full advantage of the criminogenic opportunities presented to them – why should they scan all the items, especially those that are perceived as expensive and/ or poor value for money? This is a major challenge for introducing MSP technologies and the development of a viable and credible risk model – as the physical shopping experience begins to meld with the virtual, then crime prevention strategies will also need to be developed that take account of and utilise the same shopper environment – the MSP App may need to become the new ‘guardian’, generating risk and removing excuses, making it more difficult to steal, and reducing the rewards on offer through clear risk amplification.

3. Methodology

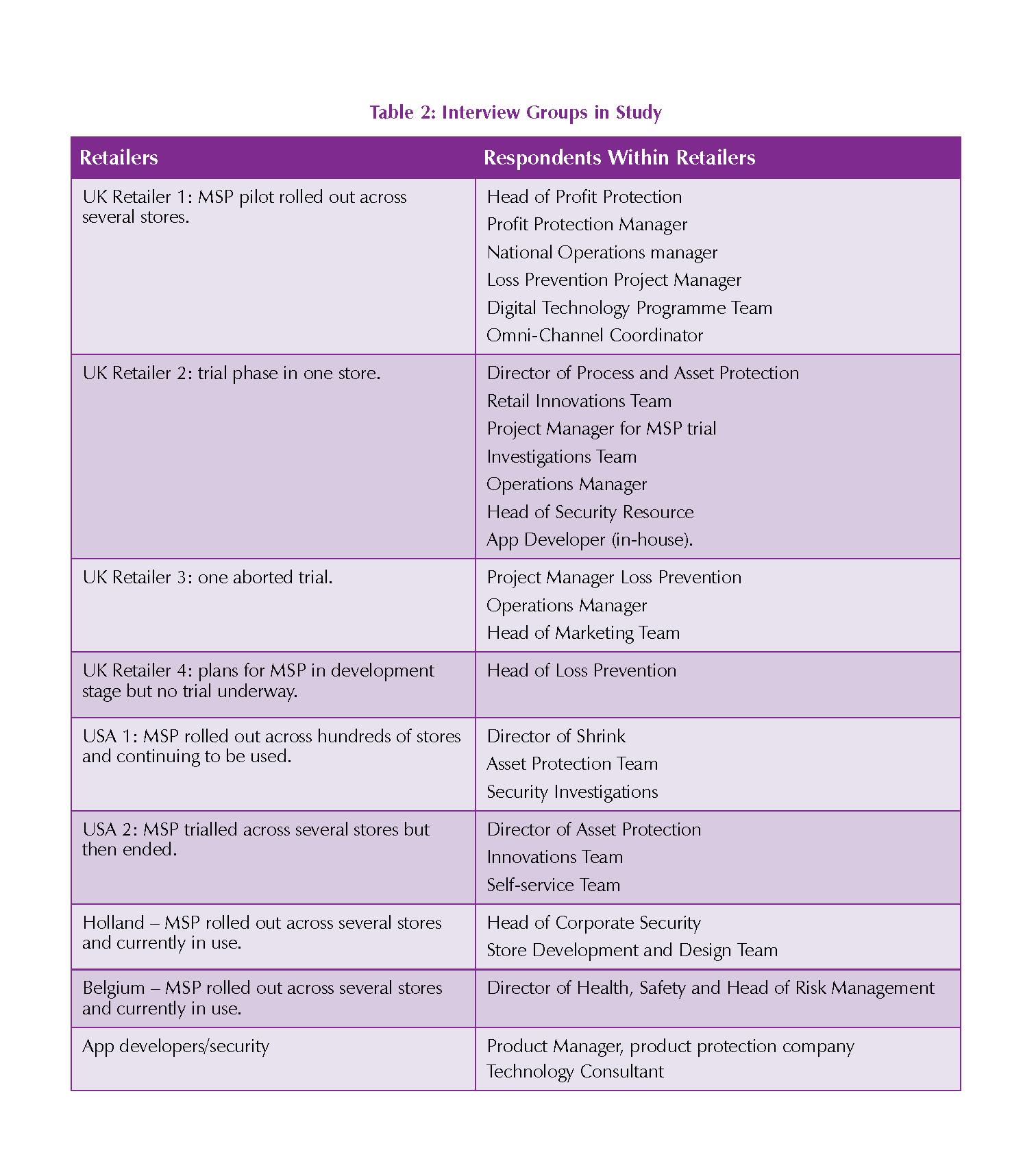

The data for the project were collected from interviews with staff involved in the development and implementation of MSP systems, visits to stores where systems were in use and through analysis of shrinkage data.

Table 2 presents a list of the participants included in the study and their respective roles. Overall, four major UK retailers were included, two USA, one from Belgium and one retailer from Holland. Two interviews were also completed with App developers/security experts. The key personnel interviewed were involved in developing or piloting MSP systems or were loss prevention personnel responsible for identifying risk and monitoring shrinkage across the company.

The interviews with retailers and App developers covered a number of themes. These included:

- Current roll out of mobile scan and pay in the company: if they have any MSP options in place across their stores, how it works, how many stores it operates in, and any problems observed with its operation.

- Views on the development of mobile scan and pay across retailing: what the benefits are to retailers and shoppers, what the challenges are in its development, whether mobile scan and pay is likely to become used widely throughout retailing.

- The risk of loss in the retail environment: the extent that MSP might increase losses, how it could increase losses, how shoplifters might exploit such systems, how such systems would work with existing legislative requirements (such as the sale of age restricted products), how it will be managed by loss prevention.

- Product protection: the extent that a deterrent effect can be built into existing product protection, how MSP will work with current product protection devices such as tags, how MSP and non-MSP customers will be monitored in-store, what future plans exist for product protection (whether technologies such as RFID and CCTV have a role to play), whether a credible detection component at exit gates can be created.

In addition to these formal interviews, a focus group was also conducted with a retailer who had run a trial of MSP. The principal aim was to consider issues around loss prevention and how such loss might be mitigated through the following:

- Store design: zones of control – how zones of control might be developed. Store layout and design – the importance of visual cues and signage to shoplifters.

- Product-based technologies: such as tags, RFID, and safe cases.

- Store-based technologies: such as CCTV, exit screening/barriers; techniques of payment validation: bag and receipt checks; product weight confirmation plates; and tolerance for validation research.

- Consumer-based technologies: App based preventative measures; device security, such as wipe data and replace mobile wallets instantly; use of identity verification technology (such as PIN number or fingerprint); and store data in cloud rather than on device.

- People based approaches: utilisation of existing security and members of staff.

- Store processes and procedures: training of staff.

All interviews were recorded and analysed using a themed analytical approach (Turley et al, 2011). This approach is common in the analysis of semi-structured or qualitative data as it allows for reoccurring themes to be identified.

In addition to the interviews, visits were made to stores (in the UK, USA, Belgium and Holland) where versions of MSP systems were in operation. In all stores (accept one) visits were overt in that they were undertaken with staff from the organisation. However, several covert visits were also made to a UK store where an MSP system was in operation. The aim of these store visits was to use the MSP systems in order to identify problems that might be experienced by users, potential opportunities for theft and opportunities for crime prevention. Extensive fieldwork notes were taken after these store visits which were then subsequently analysed.

Shrinkage data was provided by just one of the retailers where MSP systems were being trialled. As detailed in the Findings section below, getting shrinkage data from retailers is notoriously difficult – it is regarded as highly sensitive data and rarely published beyond in aggregate form covering multiple retailers as part of regular surveys. In order to protect the identity of the retailer only limited information can be provided on the data itself. The retailer is a large international grocer with many hundreds of stores and a turnover in the many ✪billions5. They provided data covering a 12 month period collected from hundreds of stores offering the consumer a choice of traditional means of shopping via fixed and staffed checkouts, or the option of mobile shopping via a scan gun provided by the retailer or the opportunity to use a bespoke shopping App installed on their own smart phone. For both forms of mobile shopping, payment was via dedicated fixed terminals overseen by store staff.

The data made available included the following variables:

- The total number of completed shopping trips.

- The number of shopping trips that used a scan gun compared with a mobile phone.

- The number of items purchased.

- The value of the items purchased.

- The number of shopping trips when a check audit was undertaken.

- The average number of items audited.

- The average number of items not scanned.

- The value of items found not to have been scanned.

The data covered nearly 12 million mobile scan shopping trips with a total value of ✪21million (6 million items). Of these, 1 million trips were subject to an audit, which generated data on the number and value of items found not to have been scanned by the consumer. On average, 6 items were selected to be checked as part of an audit, from an average basket size of 30 items (20%). Unlike other retailers utilising check audits, identification of non-scanned items did not trigger a full scan of all items – only the number selected for review were checked. Unfortunately, it was not possible to disaggregate the mobile shopping data and so all data presented in this report covers both mobile scanning technologies used by the case study retailer (retailer provided scan gun and consumer owned smart phone).

4. Key Findings

4.1 Current Developments in Mobile Scanning

All retailers in the study were at different stages in the development of MSP. In the UK, one retailer was piloting a MSP system across several stores; another was in the process of conducting a trial within one store, one had piloted a system though the company had (for the time being) shelved roll-out plans and another had not got past the planning stage of a pilot project. All of the four retailers from the international sample had rolled out MSP systems and three were currently running versions across their stores (one had withdrawn the MSP option from its stores). Across the majority of the retailers in the sample, MSP development and implementation was currently focused around only a scanning option – thus allowing customers to use their own mobile phone to scan items – rather than developing a payment wallet. Only one retailer in the study was currently trialling a scan and payment wallet with their MSP system.

4.2 The Benefits of MSP for Customers and Retailers

Although the pace at which MSP systems were being developed and implemented across the sample retailers was slow (and in many cases not without difficulties), respondents highlighted several potential benefits. Many of these echoed much of what has been published in the media (see for example, Halliwell, 2013; Walsh, 2013) and in previous research (Taylor, 2013; Aloysius and Venkatesh, 2013), though are worth recounting again here.

Respondents pointed to consumer convenience and how MSP makes the purchase process easier and quicker as key benefits. As one respondent stated, ‘customers don’t have to empty their trolley and reload it all again at the end… which ultimately speeds up the process’ (Interview 2). It also enables customers to know exactly what they have spent at all points of the shopper journey and eventually ‘convenience payment’ within the aisle (rather than at a payment bank at the end of the shopping journey) should be possible. Indeed, the potential for the ‘personalisation of shopping’ (Interview 2) was thought beneficial as it allows the customer to keep a closer track on their purchase history and any loyalty points accrued. However, it was thought that one of the real key benefits to customers would be through utilising geo-location data and real time messaging with integrated webpage/ store hubs. Geo-location data could allow stores to identify where customers are in-store, which could then be linked to store maps and directions to specific products. Integrated webpage/store hubs would allow customers to browse goods via the retailer webpage, while also being sent information about where the products are located in-store, if they are available and at what price. There is also the potential to relate items purchased to other commonly purchased items (shave gel to razors, tonic to gin, children’s shoes to children’s clothes etc.) and to send the customer real time push notifications about offers on other related products.

Interviewees identified several key benefits of MSP to retailers. Whilst much has been made of the potential savings that might be made on staff costs as a benefit of customer self-check-out (O’Donnell & Meehan, 2012), this was also cited as a key potential benefit of MSP. One retailer suggested that for a trial of MSP they were ‘attracting away from the main banks rather than the self-check-out (SCO) so that was definitely the audience we wanted to target’ (Interview 2). For some retailers the use of this technology would offer two staffing-related opportunities: to enable more staff to be utilised away from checkouts and on to more customer-focussed services such as in-aisle assistance; and a reduction in the overall staff hours allocated to stores. A knock on effect of this would also be that there would be savings on the purchase costs of physical checkout equipment (as less would be needed) as well as the associated maintenance and cash handling costs (Interview 4). In addition, less physical check-out equipment would free up more space for product displays. However as one respondent mentioned there might be a shrinkage cost involved: ‘it potentially takes out a lot of labour, it might increase shrinkage, but profitability might improve [the increased cost of shrinkage would be less than the labour saving]’ (Interview, 4). Indeed, it has been highlighted that as shopping patterns change (particularly with the increased usage of online/click and collect shopping), many physical stores might become less efficient to operate and retailers will need to reduce store numbers or cut costs within stores (Ramchurn, 2012). Thus MSP could offer some ‘potential long-term savings in staff costs’ (Interview 4). Other key benefits that MSP was thought to offer to retailers related to customer retention and the marketing of products. As eluded to above, forms of loyalty bonuses and product offers could be offered to MSP customers. Ultimately, registering customers as MSP users also allows retailers to hold even more information about them. This might allow retailers to ‘sell shopping pattern data to analyse’ (Interview, 4) and yet further personalise the shopping experience.

Despite these benefits there was some concern expressed over the customer up take of MSP. As one of the interviewees stated:

Everyone’s telling [retailer name] they want things on their phone, they want Apps, they want to make shopping easier, but actually when it came down to it, we found that our customers prefer doing the normal shopping routine of coming in, picking up their goods and waiting to get through to the till, and even in those stores where it’s very busy, people were happy just to stand and wait, rather than to use their mobile (Interview 1).

Indeed, there was some suggestion that in some locations and for some demographics the move to MSP might represent a cultural shift that might be slow to be adopted. As one retailer said ‘especially in [place name], to change a 100 year shopping culture, expecting them to use their own device, go through registration, download an App to do it … they’ll probably think it ain’t worth it’ (Interview 3).

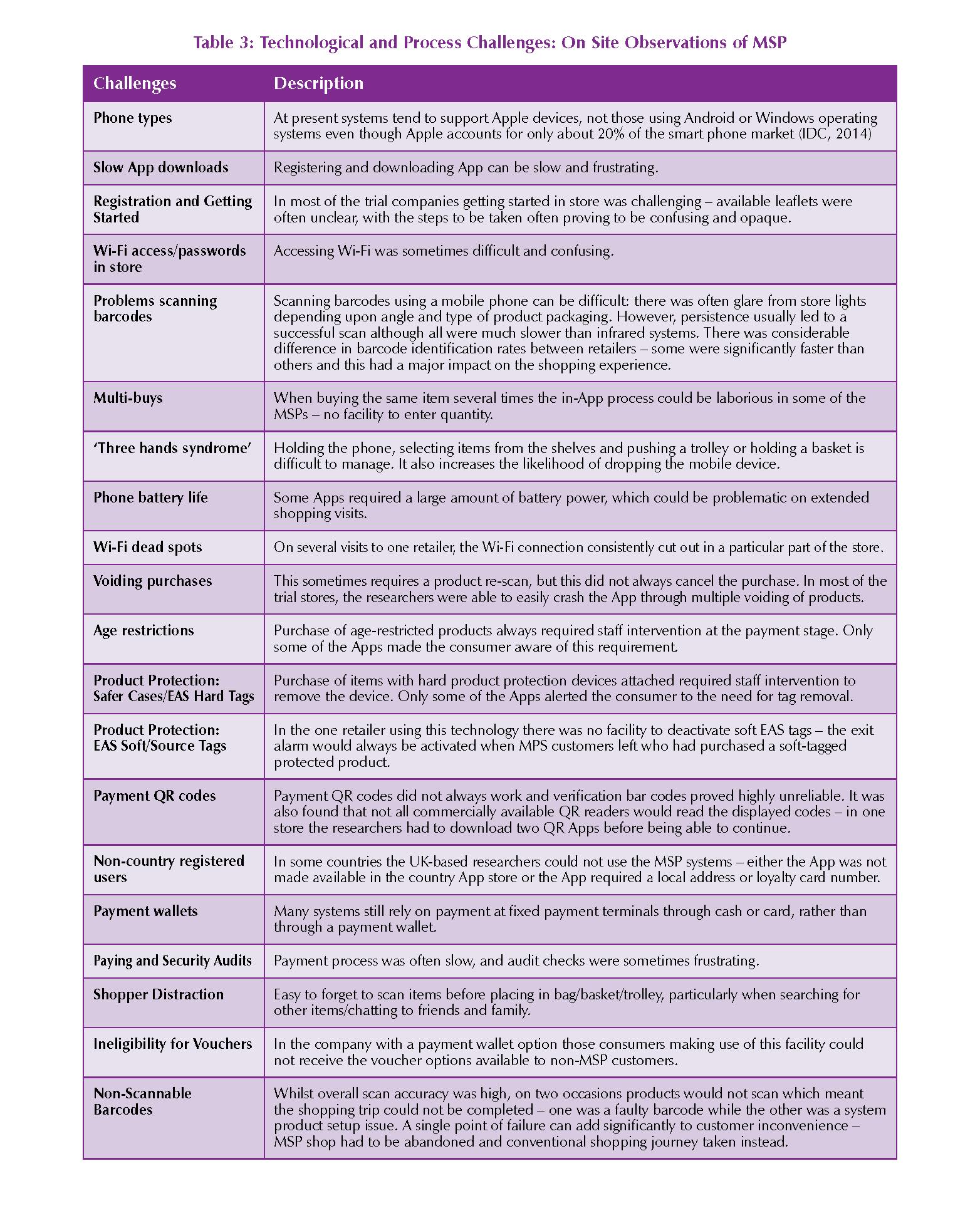

4.3 Technological and Process Challenges

The in-store trials and interviews with retailers highlighted several technological and process challenges to MSP (see Table 3). Many respondents acknowledged that they were still feeling their way around the technology and that the MSP systems were far from perfect. Indeed, many were – for the time being – focusing on developing a mobile scan option (rather than a payment wallet) – either through developing existing versions of their own hand-hold scanning guns or developing new mobile Apps solutions.

At present, most MSP options are based upon supporting Apps downloaded via iTunes and operating on an Apple device – options for Android or Windows phone users are currently limited. In interview, one respondent mentioned the results of a trial in one of their stores where customers had problems in downloading the App, and said ‘it was slow and cumbersome’ (Interview 10). Indeed, our experience with one other retailer was that registering and downloading the App was very slow.

As detailed above the research team uncovered and experienced a wide range of challenges associated with using current MSP systems. Indeed, access to good quality free store Wi-Fi was found to be key to the successful operation of MSP systems – one operator made this especially difficult by having two separate WiFi networks in the same store, only one of which would allow MSP to work! However, a more significant and common problem highlighted in the interviews and with our in-store trials related to the relative ease with which products could be scanned. Sometimes it was difficult to align product barcodes to the phone camera and it could be difficult to carry a phone, a basket and scan a product all at the same time (the three hands syndrome). Such scanning problems are not only a potential source of customer frustration, but also create problems for retailers in identifying when customers make genuine scan errors or when they claim items would not scan (as a technique of neutralisation in relation to theft). While some retailers were thinking about how to deal with the ‘three hands syndrome’ such as offering consumers a wrist or neck lanyard or some form of device docking bay on trolleys or baskets, none had taken this very far. Concerns were raised about lanyards in terms of store liability should the lanyard break and the device be damaged, while the latter raised concerns about designing a docking station that would fit all available mobile devices and not raise the risk of theft when consumers moved away from their trolley/basket.

What was particularly revealing from the researcher’s in-store use of MSP was the relative ease with which products could be put into a bag, basket or trolley without first being scanned due to genuine distraction. The grocery store where most of the trials were undertaken is a large 87,000 square metre store – locating products on an extensive shopping list can be challenging, especially when under time pressure. By the time a product had been located and thought had turned to the next item on the shopping list, it was relatively easy to miss out the scan step. In addition, when two people were shopping together it was again easy for the scan step to be missed by the non-MSP user putting products into the bag, basket or trolley. At the end of one shopping trip the researcher found that 10% of items in a basket had not been scanned through genuine error caused by distraction (the items were then scanned before payment was made). This raises an interesting challenge for MSP systems – retail stores are complex, often busy spaces crammed with messaging aimed at tempting the shopper into making impulse purchases. Retailers may find that an increase in non-malicious ‘thefts’ due to non-scans are simply an inevitable by-product of overlaying the requirement to accurately scan all items onto an already ‘noisy’ and immersive shopping experience – the shopper is being asked to do too many things at once. Previous research has highlighted that having too much stimulus or too many activities going on in one environment can result in ‘directed attention fatigue’ (Berman & Kaplan, 2010) where humans are distracted and fail to concentrate on one task at a time. Indeed, when one considers the more traditional staffed checkout or indeed the SCO environment, activity at this stage is primarily one-dimensional – scanning all the items in the basket or trolley as quickly and (retailers would hope) accurately as possible. Few distractions, beyond some nearby impulse purchase options, exist – the consumer or the member of staff is largely focussed upon the task in hand.

Some respondents stated that results from their trials had revealed that phone battery life had been an issue for customers. Indeed, on longer shops (50+ items) this was found to be a problem although as consumers become more familiar with the system the length of the shopping journey may be reduced, saving on battery life. However, a more frustrating issue was around WiFi dead spots in store that could lead to the App failing to register a product at all. Further to this, cancelling a purchase normally required a re-scan of the product, which further slowed down the shopping trip.

In most MSP systems the final part of the shopping trip mirrors the experience of SCO customers. At present age restriction checks have to be carried out by staff, with some of the trial Apps making the consumer aware of this when they scan the item while others would only flag up the need for validation at the point of payment. Similarly, some of the MSP systems would alert the consumer when a product was protected with an anti-theft device that would need to be removed by a member of staff at the point of payment or at a customer service desk. The payment process was a challenge for all the companies taking part in the research – only one had integrated a payment wallet into their App; the others relied upon the consumer taking their device to either a regular checkout or a bespoke payment area or an area where SCO and MSP customers could be processed together. The experience of using the payment wallet was mixed – a quirky in-store process, which required a time limited barcode to be found in the store before a payment could be processed, meant that it was seldom quick and often frustrating, leading to little if any time saving compared with SCO systems. The company operating this recognised the problem and claimed that Version 2 of the App planned to resolve this issue.

The reluctance to offer an in-App payment option by most of the companies was partly a technical issue of ensuring adequate security for the consumer, but was mainly driven by concerns around ensuring customer compliance – they were very nervous about allowing a user to pay anywhere in the store because of the total absence of available control. Even in the one company using a mobile wallet option, they instructed users to go to a designated area where a member of staff with responsibility for SCO was nearby to monitor activity and undertake any required check audits.

4.4 The Potential Impact on Shrinkage

It was clear that retailers had given some thought to the potential crime problems that might be generated through MSP (though this was speculative rather than proven through any analysis of shrinkage or loss). Indeed, it was thought there would be an impact upon shrinkage, but the question for many was whether increases in shrinkage could be balanced with reductions in labour costs: ‘if we do see an increase in shrinkage in five years’ time, there’s a pay off between that and the wage numbers’ (Interview 2).

Primarily, it was identified that MSP might generate crime or loss in four ways:

- Theft through malicious non-scanning of goods.

- Non-malicious loss through non-scan/scanning errors.

- Physical and verbal abuse against staff generated via audit checks.

- Transaction frauds or fraudulent use of payment wallets.

Importantly, a distinction was made between the types of ‘offender’ who might exploit MSP. There was a suggestion that MSP would not be used by shoplifters who chose to conceal goods or even overtly walk out [‘walking’] (see Bamfield, 2012). As one respondent said ‘it could provide the camouflage for theft’ (Interview 9), though another stated ‘if you wanted to nick a pack of razor blades, why go through the whole signup up process with goods?’ (Interview 4). Indeed, Aloysius and Venkatesh (2013:51) suggest shoplifters see potential opportunities to use MSP systems, but at present do not see MSP as likely to ‘make these activities [shoplifting] either easier or more difficult’. However, in the same research it was reported that one shoplifter suggested ‘it was only a matter of time… that they would figure out new ways to exploit the system’ (Aloysius & Venkatesh, 2013: 51). Respondents in this study suggested that moving towards the ‘ultimate in self-service’ (Interview 10) might not only send out the wrong physical cues to potential offenders (Cardone & Hayes, 2012), but those shoppers who might not necessarily plan to steal could take the opportunity to exploit weaknesses in systems if possible. Similar to research conducted on SCO (Beck, 2011), it was thought retailers might actually encourage shoppers who fully intend to scan and pay for products to engage in criminal activity. As one respondent said: ‘what you might see is people who traditionally don’t intend to steal but realise… when I buy 20, I can get five for free… maybe I’ll continue to do that’ (Interview 4).

Using the language of opportunity theory several possibilities emerge in relation to the crime generating properties of MSP.

Ease of Effort/Access to Products

Whereas traditional counter shopping limited access to goods, the rationale for customer self-service, SCO and MSP is that customers have open access to products and within the SCO and MSP model, the customer takes responsibility for payment with limited or no staff involvement at all. As one respondent commented ‘it’s the ultimate in trust’ (Interview 6) or as another said ‘they call it ‘Scan and Rob’’ (Interview 8). Thus, MSP potentially promotes ease of effort for theft by removing any human contact throughout the shopping process and removing (possibly most importantly) human contact at the final payment stage of the shopping journey. As succinctly put by one interviewee; ‘you scan it and you walk … you’ve got no controls in place’ (Interview 5). Of course the self-service culture has meant retailers have implemented a range of product protection devices – hard tags, soft tags, spider tags, safer boxes/cases – to promote risk throughout the shopping journey. However, one respondent suggested an unintended effect of MSP might be a sort of ‘displacement effect… where due to the ease… we [might] see a greater number of non-protected items going missing’ (Interview 4). Indeed, another respondent suggested in mystery shopping trials of one MSP system, even where product protection alarms were activated there was little response from retail staff: ‘he didn’t pay for half… set the alarms off, they ignored him, walked back in, set the alarms off, they ignored him’ (Interview 5). Indeed, in one store trial conducted for this research, it was identified that when a validation check was not conducted at the point of payment it would have been easy to steal non-protected items. In another store visit completed for this study, the main reason for the ease at which goods could have been stolen was because validation staff were more concerned with processing customers quickly through the payment process (as staff were getting frustrated over the continual technical glitches with the payment wallet option) rather than conducting re-scan/audit checks.

Increased Rewards for Offenders/Non-scanners

The MSP environment might generate long-term rewards for offenders/non-scanners. Indeed, several respondents suggested that non-scanning behaviour could become part of the routine behaviours of some shoppers. At present, there is some evidence that nonscan is a part of the behaviours of some SCO customers; ‘people will always take advantage of opportunities. You see the self-service figures, one in five admit to stealing on self-service’ (Interview 1). Therefore, there is a possibility that some shoppers might begin to perceive certain stores as easy targets and thus increase the frequency at which they use/target them. Indeed, studies of repeat victimisation illustrate that offenders select targets based upon risk heterogeneity factors – where a target is so attractive they will select it to commit crime (regardless of whether it has been a successful target for them previously) and as a result of successfully committing a crime then return on another occasion to the same target – known as ‘event dependent repeat victimisation’ (Farrell & Pease, 1993; Farrell, 2005). Indeed, several interviewees suggested that – as with SCO – MSP could act as a risk heterogeneity factor – where people are attracted to stores in the knowledge that they can chose to not scan certain products with relatively little risk of being caught. As one respondent suggested, ‘you get away with it once and then you can just repeat it again and again…’ (Interview 7).

Reduction in Risk Perception

Several studies have shown that surveillance or various forms of capable guardianship are important in the prevention of shop theft (Tilley, 2010; Butler, 1994; Cardone & Hayes, 2012; Beck, 2011). For example, the number of ‘place managers’ (store employees) throughout the store, using customer meet and great practices (Tilley, 2010), increasing staff vigilance (Butler, 1994) and formal surveillance (such as security guards) can all impact upon risk perception (Butler, 1994; Cardone & Hayes, 2012). Thus, increased anonymity reduces the perception of risk (Aloysius and Venkatesh, 2013). Within the MSP environment, the sense of risk perception or control is reduced as all elements of the customer journey can be completed without human interaction. Indeed, a further likely long-term consequence of MSP is that the number of place managers will be reduced, as one respondent said ‘there are benefits [from MSP] in labour savings, but there could be other problems with that’ (Interview 4).

Likely Excuses

Previous research has highlighted that SCO allows consumers to use ‘ready-made excuses’ (Beck, 2011: 210) for offending (the self-scan defence). Therefore, giving customers the freedom to self-scan gives them the opportunity to blame faulty technology, problems with the product barcodes or claim that they are not technically proficient as reasons for non-scan (Aloysius & Venkatesh, 2013). Indeed, issues around the ‘selfscan error’ and ‘self-scan defence’ regularly came up in the interviews. Of course, scanning error is not only common amongst self-scan users, but checkout operators also frequently non-scan items. This led one respondent to suggest that some of their stores had actually seen improvements in shrinkage because ‘the customers were more accurate [at scanning] than the cashiers’ (Interview 7) or are more likely to ‘double scan’ to make sure something was included in their shopping basket – in effect pay more than once for the same item.

However, one of the key problems where customer non-scan is observed is in proving intent to steal items and whether prosecutions can be made or not. As one respondent said ‘I scan 20 items and I don’t scan five, am I a thief or am I someone who’s not very competent?’ (Interview 4). Another noted, ‘I don’t think we could ever prosecute anybody as things exist today, because they could always fall back on the argument ‘well, I pressed the button, I thought I’d scanned it’’ (Interview 2). Indeed, observations conducted in MSP stores for this research were that validation staff were always more than willing to accept this as a form of defence (even when we had knowingly not scanned items). Deciding when multiple non-scanning events constitute a pattern was something that all of the retailers were keen to understand and it was certainly a key component of the main risk generator currently available in the MSP shopping journey – the ‘random’ audit capability (see below).

Efforts have been made within MSP systems at the point of payment to ensure that customers are sure they have scanned all of their items. Most systems have an onscreen prompt, either in the App or on the payment screen, that asks the customer ‘are you sure you have scanned all of your items’. If a customer then proceeds to press ‘yes’ knowing they have not scanned some items this can be proof of intent. One respondent said:

…but where I’d feel comfortable convicting [on SCO]… this guy scans three items, pays for those three items, punches in his card details, which is great for us because we can track him… but there’s five items that haven’t been scanned, and soon as he’s got his receipt, he bags those up. That to me would be strong enough to put in front of the police and say this is absolutely premeditated, he’s decided he’s going to steal them, you can see by his behaviour he’s made no attempt to pay for them and he’s left without paying for them (Interview 4).

Across some jurisdictions retailers have been concerned about potential reputational damage that might be caused by prosecuting customers for not scanning a small number of items. One retailer suggested that its self-checkout option was abandoned as ‘too many of our desired customers made little mistakes’ and as ‘theft is strictly regulated here in [name of country], you need to prosecute’ (Interview, 6). Indeed, issues in relation to intent are further confused by where the last point of sale (POS) will be in future MSP systems. At present it is clear where the last POS is in most retailers, though as MSP payment systems develop, potentially payments could be made in the shopping aisle or (Wi-Fi permitting) in the car park of the store. This creates problems in understanding where in the shopper journey the final payment point is. As one respondent said in relation to MSP, ‘there is no longer a last point of payment and by law we would normally stop people after that’ (Interview 2).

Likely Provocations

At present, there are a number of points in the MSP shopper journey that could trigger disputes with staff. Our store visits identified frustration points when products would not scan, when staff had to intervene to remove EAS devices/do age verifications and when payment wallets would not work. For example, on one shopping trip the researcher was given a cash discount because of unacceptably long delays in processing a MSP payment. Indeed, Aloysius and Venkatesh (2013) noted that continual intervention from staff at the POS in relation to age-restricted items and exit validation audits (or re-scans) can generate customer frustration. As one respondent suggested in relation to validation audits, ‘customers hate it and we know it’s a crap experience and we accept that’ (Interview 8). However, most respondents suggested customers are generally fairly relaxed about having their shopping subject to exit/ validation audits as long as checks are conducted in a non-confrontational and educational way. It was noted that validation audits normally ‘only lead to aggressive behaviour when customers have not-scanned items correctly’ (Interview 6). Indeed, Aloysius and Venkatesh (2013) suggest customers find validation audits before payment to be less intrusive than checks after the transaction has been completed. Interviews also revealed that UK based customers might have a greater tolerance to validation audits than their European or American counterparts. However, further research is required to ascertain how tolerant customers are of such processes.

Previous research has also suggested that MSP might aid those wanting to engage in transaction frauds (Bamfield, 2012) – using false barcodes, bogus receipts, card fraud and colluding with staff [‘sweethearting’]. Our respondents seemed less concerned about fraudulent activity than non-scanning. However, three did highlight concerns around fraudulent activities. One noted that a concern in the business was around the production of self-scan labels that might be stuck on products. While any shopper can label switch, it was suggested it might be easier for MSP customers to do so without being detected as it might not look so unusual for them to be carefully looking at product barcodes in the aisle – which might offer an opportunity to change labels. Other concerns were expressed over fraudulent payments with one respondent giving an example:

…in the early days of the [electronic payment] wallet, we had some attempted fraud and we recognised that because an account was created, a number of small shops [trips] were done through a card and then a big shop was attempted, on the same day. So what someone was trying to do was validate that the process worked (Interview 8).

While it was thought that the payment wallet ‘could open up a new world for fraud if customers payment details could be stolen and used via the App’ (Interview 8) it was also suggested that not only might electronic payment wallets facilitate the ease at which stolen credit card details can be used, there was also the potential for the use of fraudulent electronic vouchers or coupons. Although not mentioned in the interviews, Taylor (2013) also notes that possibility of ease of repudiation fraud – where customers may claim that they had not purchased certain items or goods that they appear to have paid for. Overall, it was apparent greater consideration needed to be given around possible fraudulent uses of MSP systems. As one respondent stated:

What we would need to understand, is the vulnerability around card fraud and how fraudsters use it either through getting other people’s details from a mobile wallet perspective, or payment method. Because that’s where it becomes quite interesting. If I steal your phone, how do we protect the App to make sure that you have to put in your password every time to check out. Or some unique identifier that says I can’t just steal your phone, do all the shopping I want, pay for it and I’m out the door with a one touch payment (Interview 4).

Finally, one of the biggest concerns raised about MSP was in relation to the potential impact on inventory accuracy. Both the non-scanning of items and theft have a ‘knock on’ effect in relation inventory accuracy and on-shelf availability of stock. As one respondent noted, certain product groups create problems. For example, ‘when someone buys five different varieties of the same dog food, do they just scan one five times, where does that leave our inventory accuracy?’ (Interview 4). Also it has been observed that customers often attempt to, but wrongly, scan loose products such as fruit/vegetables and multi-buy offers – when there is a buy one get one free, do you scan the ‘free’ item? Indeed, one respondent noted ‘the inventory drift could have quite a significant impact on the store in terms of availability sales’ (Interview 4). This in turn can significantly affect other aspects of the business such as home delivery where poor availability can lead to retailers having to compensate customers for missing items.

4.5 Analysis of Shrinkage

The Difficulties of Measuring Retail Losses

While a number of retailers have been operating versions of MSP for the last few years, no data has been published to date analysing the impact these systems have on rates of store ‘shrinkage’ – the term used by the retail industry to describe a basket of losses ranging from shop theft to products going beyond their sell by date. While this is a widely accepted global term to describe ‘retail losses’, there is in fact no standardised definition as to what it actually means. For some it refers to all the losses that are ‘unknown’ within their business, in other words those losses that are found when store audits are undertaken and a comparison is made between what the retailer thinks should be in a store (received stock minus sold stock) and what is actually present (the difference between expected and actual stock holding). For other retailers shrinkage refers to only those incidents which are criminal in nature – internal and external theft, while others prefer a more inclusive definition that also takes account of losses such as the value of those products which have gone beyond their sell by date, or have been discarded because they have been damaged (often described as process or administrative losses). This high degree of ambiguity makes efforts at benchmarking within the industry notoriously difficult and subsequent results highly unreliable.

It is further complicated by the fact that retailers also vary in the way in which these losses are measured, with some preferring to calculate loss based upon the cost price of the items lost (the actual price paid by the retailer for the product) while others prefer to use retail prices (what the retailer would have received had the product been sold at the price offered to consumers), arguing that there are a whole host of consequential costs associated with lost products, such as transportation, staff costs etc. that are not reflected in the cost price. Depending upon the margin imposed by the retailer this could inflate or deflate the shrinkage figure considerably, perhaps by around about 60-70%.

On top of these significant definitional issues, retailers also face an enormous problem actually identifying the causes of their shrinkage losses. This is because a large proportion of losses (depending upon how they are defined) will only ever be uncovered when a physical audit of stock in a retail stores is undertaken (as described above) and this, while varying between retailers, will normally be an annual event. This means that losses may remain unknown for up to 12 months, making identification of when incidents happened, where they occurred and by whom almost impossible to identify. This has led to the development of a ‘guessing game’ within the industry where efforts are made to try and estimate what might be the likely causes of these losses, which unfortunately generates data more useful in gauging how the industry perceives the problem rather than measuring the actual problem itself.

To add a final further complication, retailers rarely if ever publish their rates of shrinkage – they are not typically included in annual reports and few will share their losses with external organisations. Understanding this reticence is difficult to explain beyond organisational concerns about reputation (high losses viewed as a sign of poor management) or increasing the risk of being viewed as an easy target by criminals (high losses means poor security). Either way, retailers do not readily make this type of information available to researchers and when they do they frequently insist upon anonymity and strictly enforced Non Disclosure Agreements (NDAs).

The reason for this preamble on what the term ‘shrinkage’ means and why data on its prevalence is difficult to find is to put the ensuing data into a context. Of the 6 retailers that agreed to help with this research only one was prepared to share any data on the impact mobile technologies might have on rates of shrinkage. In order to protect the identity of this retailer we have to be cautious in the way in which we describe and present the results, including to a certain extent how they were generated. This is less than ideal but the researchers have taken the view that given nothing is currently available in the public domain on this issue then a partial data set is a move in the right direction.

Measuring Loss in a Mobile Shopping Environment: A Case Study

As detailed in the Methodology Chapter, the retailer that agreed to share data with the research team is a ✪multi-billion turnover grocer with many hundreds of outlets providing a wide range of products and services. It is important to reiterate the way in which the audit data was generated and the opportunities and limitations of this information. Like many of the other retailers installing this technology, the key defence against abuse was seen to be the threat of an end of shop audit (see below) when a customer is stopped and some or all of the items in their bag, basket or shopping trolley are checked for accuracy and where a discrepancy is found it is either added to the customer’s bill or removed and replaced back on the shelf. This method arguably generates the most accurate ‘shrinkage’ data ever available to a retailer – the type and value of a product that is either being attempted to be stolen, or has been ‘forgotten’ by a consumer, is precisely measured over a relatively large sample of shoppers and over a relatively long period of time. For the majority of unrecorded shrinkage losses retailers typically have almost no idea of where, when and how losses have occurred, and so this level of granularity on specific forms of shrinkage losses is very rare indeed.

As detailed above, the causes of most shrinkage losses are unknown and are only usually uncovered at annual stock audits when the location, time and perpetrator are all unknown. With this type of audit data, all of these factors are known except for the motivation of the offender, which remains in doubt – was it an attempted theft (malicious) or simply human error (non-malicious)? So this is a potentially rich vein of information to understand the extent to which consumers using this technology are not scanning items they have put in their bag, basket or trolley. Where this data is more problematic is that the case study retailer tasked a member of staff undertaking an audit to only check a relatively small number of items – on average 6 – out of a typical basket size of 30 items. If one or more non-scanned items were found amongst the 6 items selected for audit, then they would be either added to the customer’s bill or removed and replaced back on the shelf, but the remaining items would not be checked for accuracy. So, in effect, the 6 items were used as a ‘sample’ of the total contents of the shopping basket.

Some caution has to be expressed with this method of data collection as there are two principal flaws. First, while retail staff undertaking an audit were told to try and choose the selected items randomly from a bag, basket or trolley, inevitably items from the top are much more likely to be checked. This could allow malicious thieves to ‘bury’ non-scanned items at the bottom of the bag, basket or trolley to avoid selection and hence reduce the number of non-scanned items recorded. Second, if one or more non-scanned items were found amongst the few items chosen for audit then this is highly likely to suggest that other non-scanned items are present in the bag, basket or trolley, but these would not be found (for other retailers taking part in this research the identification of one or more non-scanned items would automatically trigger a full scan of all items in the bag, basket or trolley). This decision to limit the scale of the audit parameters inevitably reduces the overall number and value of items found to have not been scanned.Unfortunately the data provided by the retailer did not separate audit data relating to shopping trips using scan guns provided by the retailer and those shopping trips which used a customers’ mobile phone – the data was only available in aggregate form. While this limits our ability to talk specifically about the risks associated with MSP devices, the processes employed by the case study retailer were almost identical in terms of the way in which payment and audit were carried out for both types of mobile shopping.

The Case Study Data

As detailed above it is only possible to offer generalised data in order to protect the identity of the retailer. The data presented is based upon nearly 12 million shopping trips with a value of just over ✪ one billion in sales, over a 12 month period of time. Of those trips only 2% or about 250,000 were shopping trips where a mobile phone was used. Of those trips, the vast majority (80%) utilised an iPhone compared with an Android device (20%). At the present moment, the data suggests a very low take up rate for this technology, with consumers much preferring either the traditional form of shopping (self selection and scanning at a staff checkout) or the use of a handheld device provided by the retailer (a scan gun).

Of the nearly 12 million completed shopping trips some 1 million were subject to an audit, equating to just over 6 million items that were checked for scan accuracy. The total value of the audited items was over ✪21million with nearly ✪850,000 being found not to have been scanned. This equates to a shrinkage rate (calculated as a percentage of retail turnover) of 3.97%.

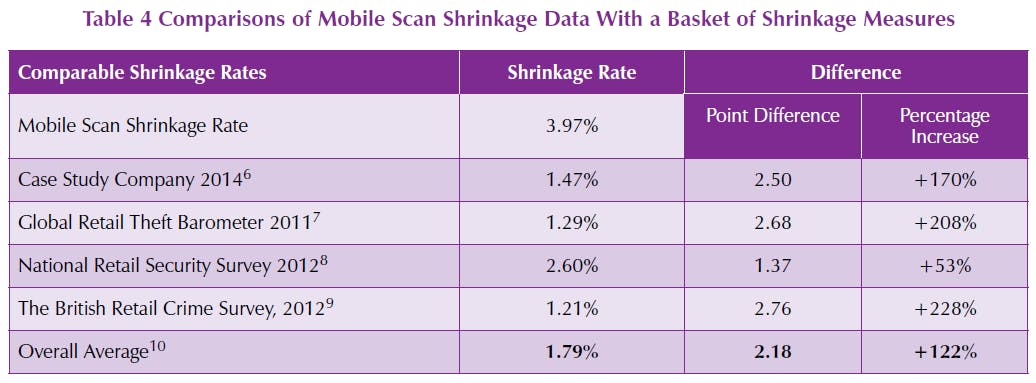

So how does this figure compare with other known shrinkage numbers? There are a number of international surveys undertaken to measure the rate of shrinkage in the retail sector. For purposes of comparison, four measures have been selected:

- The agreed comparable shrinkage rate for the case study retailer taking part in this study.

- The Global Retail Theft Barometer, which is the survey with the broadest global reach (the 2011 edition has been selected because it is considered as the most recent reliable version of the survey) (Bamfield, 2011).

- The latest available rate from the National Retail Security Survey (2012), which is the longest running shrinkage survey, though it only covers the USA (Hollinger and Adams, 2012).

- A survey carried out by the UK’s British Retail Consortium (2012). These comparisons are presented in Table 4.

What can be seen is that the rate of shrinkage generated by Mobile Scanning is considerably higher than the rate recorded by all the other studies – the highest difference being found with the British Retail Consortium where it was 228 per cent higher. Overall, when the average rate for the grocery sector data is compared, then the rate of shrinkage in Mobile Scanning is found to be 122% higher. This is a profound difference in the rate of loss and given that one estimate suggests the overall margin of profit in the European Grocery Sector is just 3% (Beck, Chapman and Peacock, 2003), then taken at face value, this rate of loss generated by Mobile Scanning could be seen as at best a not-for-profit retail venture.

There are two further points worth making. First, the case study company has not provided data on potential savings generated by the introduction of self scan technologies (as detailed earlier) that could mitigate against the significantly higher rates of loss found such as reductions in staffing and traditional check out technologies for instance. It may be that in the future this higher rate of loss may be sustainable if other store costs can be reduced to compensate for the elevated shrinkage risks associated with this type of retailing. Secondly, the data does not shed any light on the motivation of the shoppers found to have non-scanned items in their bag, basket or trolley – were they deliberately not scanning items because they were trying to steal them or had they genuinely forgotten to scan the items due to difficulties with the technology, distraction or absentmindedness? This is a critically important question in determining how to generate risk amplification with this form shopping – if it is predominantly the former, then this points to the importance of risk amplification through approaches such as audits to act as a credible deterrent, while if it is largely the latter, then it points towards the need to improve consumer communication, perhaps with products via some form of tag (see below), and or the overall design of the system. Either way, more research is needed to unpick this very high rate of non-scanning by consumers using mobile forms of scan technology.

4.6 Physical Crime Prevention, Virtual Guardianship and Risk Amplification

A key aim of the study was to consider what crime prevention mechanisms were already in place to prevent MSP-generated losses and what future mechanisms might need to be considered. It was apparent from the interviews that the key priority for retailers at the moment appeared to be around ‘proof of concept’ – to understand if an MSP system could be implemented in store and what the technological challenges were rather than what crime prevention solutions were required. The following quote characterises the approach taken: